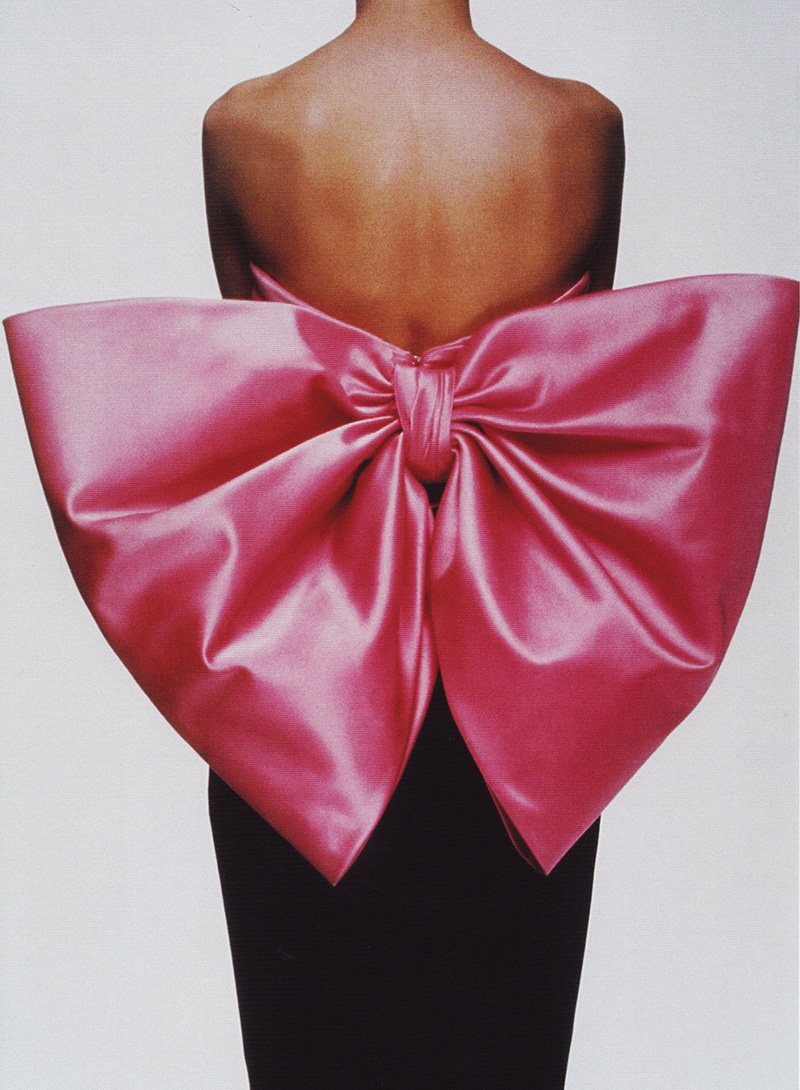

The Christmas of 1983, I got an issue of Vogue magazine in my stocking. One of the photo spreads featured the designs of Yves Saint Laurent. I remember certain ensembles with near-acidic clarity, like a brand upon the brain. The electric shock of a huge pink bow, like giant taffeta wings, affixed to the back of a black dress. It went straight to my head, and never left.

Fashion is fascinating, it’s compelling — and it can be a cruel mistress, as even the most casual viewer of the new Netflix series Halston will duly note.

The series recreates the heady days of an American designer’s dizzying, meteoric rise to the tippy top of the fashion world. Talk about balancing on the head of a pin.

Roy Halston Frowick came from humble roots in Iowa, and like many a Midwestern boy he moved to New York to remake himself. Originally a milliner, he famously designed Jackie Kennedy’s big pink pillbox by modelling it on himself (they had the same size head) before moving on to make women’s clothing. His designs — modern, breezy things that moved easily with the women who wore them — caught the flavour of the moment and soared into the stratosphere.

Halston has already been treated to a documentary take on his life and work — a sturdy offering written and directed by Frédéric Tcheng — but the Netflix production ratchets up the camp factor to a vertiginous degree. The series, which doesn’t bother too much with pesky reality, is an entertaining summation of the designer’s impact on American fashion as well as a potent evocation of the debauchery of the disco era.

In the titular role, actor Ewan McGregor chews the scenery, struts about in a turtleneck and a long red coat, and snorts enough coke to make Scarface blanch. It’s ridiculous but also richly entertaining. The most salacious aspects of the era are splayed wide — rough trade sex, extravagance, money, orchids by the thousands, bad behaviour by the bucketload. It’s easy to watch the hubris and hijinks and think fashion people are terrible people.

But the clothes! The clothes.

Aside from the raunch and glitter, the Netflix series perfectly captures the swirling loveliness of Halston’s designs. The creative apotheosis in the show takes place when the designer, stung by a sudden creative impulse, cuts fabric into whirling butterfly dresses that seem to hover around the bodies of the models. It is a chrysalis awakening, alight with the joy of free and unfettered movement.

The series also nails the demands of the business. Art yoked to and eventually choked by money is the subtext to the entire show, and Halston’s eventual fall from the heady heights of fame into relative obscurity was linked directly to money, greed and excess.

It is this moral lesson that links the all-consuming hubris of Halston to the more prosaic messages of J.B. MacKinnon’s new book The Day the World Stops Shopping.

In the book MacKinnon offers solutions, not only to stop shopping, but to shop more carefully: “The act of consuming, I realized, had become so complicated and weighted with issues that I often avoided it entirely; now, having done a lot of research on the subject, I knew what I wanted my consumption to look like.”

Any person who has set about creating a capsule wardrobe has had the same impulse. But less is more gets dull fast.

Replacing fast fashion with other, less destructive forms of consumption, like buying a coat that will last, getting shoes resoled and learning to live with bits of mending are all fine and useful, but they don’t do anything to stop the feverish desire to acquire something new that lights up the inside of one’s head like white phosphorus.

If there is one thing at the heart of Halston, and perhaps all of personal consumption, it is stoking the engine of want. Feeding it in images and fantasies, via movies, magazines, Instagram stories, window displays, marketing as far as the eye can see.

Halston arrives at an interesting moment in fashion, as many of the things that the designer originated are now becoming common practice. The affordable collections Halston designed for JCPenney in 1982, for example, long predated the current trend of designers like Jil Sander and JW Anderson collaborating with fast fashion brands like Uniqlo and H&M to offer cheaper versions of their aesthetic.

Halston was also one of the first to licence his name, branding everything from socks to luggage, housewares to perfume. The reign of less expensive ready-to-wear that came to epitomize American fashion supplanted the older European model — think Dior and YSL — of handmade haute couture.

One of the pinnacles of the Netflix drama is the Battle of Versailles, an epic showdown between American designers (Oscar de la Renta, Anne Klein, Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows and Halston) versus the likes of Yves Saint Laurent, Ungaro, Givenchy and Dior. In the episode devoted to the event, Halston takes centre stage, but the reality was far more interesting.

Still, for fashion noobs Halston is an easy romp through the annals of stylish history. If you want to go deeper, the transformative nature of clothes is at the heart of far better films such as McQueen, a documentary directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui.

Long before he reinvented British fashion as Alexander, Lee McQueen was a chubby lad from Lewisham, who used his dole money to buy the materials for his first show. McQueen’s ability to channel a broad range of ideas and references — everything from Jack the Ripper to mermaid chic — elevated his clothes from things to wear to pliable forms of sculpture.

The tragedy of McQueen, not unlike Halston, was the combination of his sweetness, perversity and a monstrous talent devoured by the demands of the market that rode him like a succubus. McQueen died by suicide at the age of 40.

Other legendary people, like editor Diana Vreeland, whose remarkable career was covered in 2012’s Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel, were able to surf the waves of the fashion world much more adroitly.

These are just a few of the great many films that lay it all out — the good, the bad, the very ugly of fashion, and of course, the flipside — the ethereal, ravishing beauty of it all.

There’s the rub.

Clothing isn’t just what we put on so that we can leave the house without getting arrested for public indecency. It’s the most effective and immediate form of identity there is. And it’s also quite simply beautiful, almost for its own sake.

For a teenage girl in the Kootenays, the siren call of that giant pink bow on a YSL dress was like a signal coming in from another, altogether more entrancing universe. Clothing then, as now, was a form of social currency — a way to be bigger, better, more exciting than you are.

What to do about desire is the question.

As a person who likes clothes, both for the thrill of the hunt and the glory of good design, I’m hard pressed to give them up. Although I’ve stopped reading Vogue, the brilliance of colour and print in a Pucci dress still stops me in my tracks like a thunderbolt.

Even as I make endless promises to myself to stop buying clothes, the love of them lingers. And love is still the hardest thing to give up. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: