The six words of a rhyming couplet — “Clear the track, here comes Shack” — have been the lyrics of a chart-busting song, the title of the hockey player’s biography, and, this weekend, the plaything of old fans sharing the story of Eddie Shack’s death at 83.

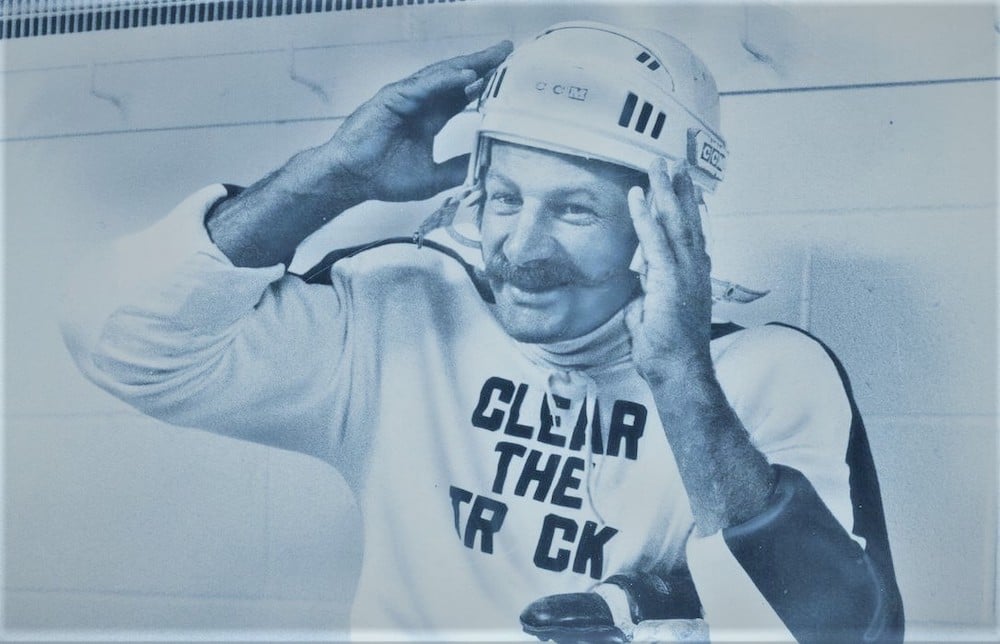

The hockey player, who was known as the Entertainer for his rambunctious style of play, became a ubiquitous pitchman for enterprises such as garbage bags, a chain of low-rate motels, and a discount soda pop outlet. He peddled blue jeans and shilled razor blades — “Shave Shack with Schick.”

He made more money endorsing products than he ever did as a player.

Stiffed by the owners as an athlete, he finally cashed in on his notoriety as a hockey wildman who did whatever it took to win a game.

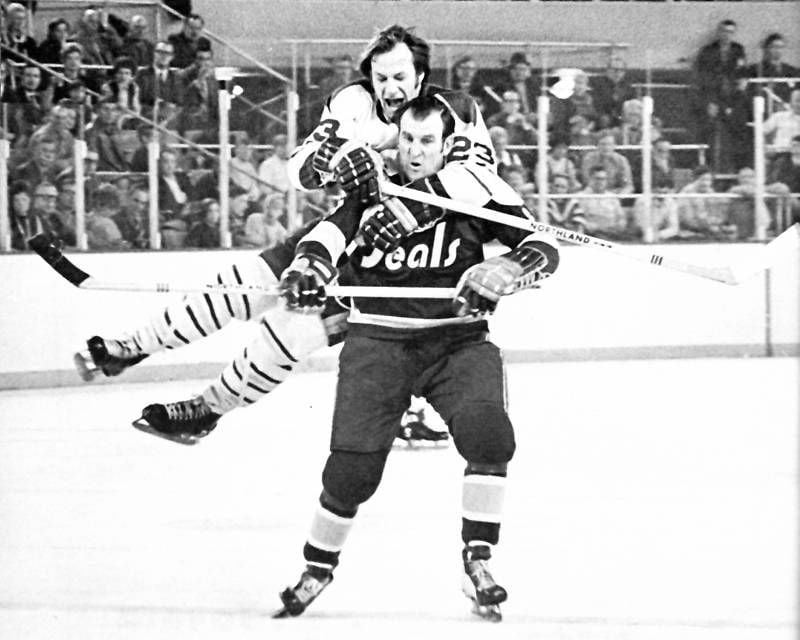

Shack was a dervish on the ice, a goal-crashing, punch-throwing, stick-swinging terror who made up for a lack of skill by being an unpredictable presence. He took part in several infamous fights, engaging in hockey-stick swordplay with Larry Zeidel and crosschecking Gordie Howe into the Detroit Osteopathic Hospital. (Shack insisted he never laid the lumber on Howe, leading Howe’s coach Jack Adams to sarcastically reply, “Maybe Howe was hit by a [rolled-up] program.”) During dull games, fans at Maple Leaf Gardens chanted, “We want Shack!” urging the coach to send the left winger onto the ice to cause mayhem. It was like taunting the teacher to wind up the class cut-up to spark a lethargic classroom.

Shack was a journeyman forward in his 17 National Hockey League seasons. He had five seasons in which he scored more than 20 goals, though four of those came after expansion diluted the league. In 74 playoff games, he only ever scored six goals. One of those, credited as the Stanley Cup-winning goal in 1963, was a shot from the point by Kent Douglas that ricocheted off two Detroit players before bouncing into the Detroit net off Shack’s ass.

Shack helped the Maple Leafs win four Stanley Cups in the 1960s. His reward was to be traded to Boston less than a month after the fourth of those in 1967. Toronto has not won a Stanley Cup in the 53 years since.

In those years, Shack became a folk hero of the kind we’re not likely to see in hockey ever again, one of the last of the lunch-bucket brigade, a working-class hero from hard-rock mining country with no money, no education, and no staff of publicists to protect him from his own worst impulses.

His contemporary Dennis Hull, the less flashy brother of Bobby (The Golden Jet) Hull and the uncle of Brett Hull, has built a post-athletic career as a banquet speaker with a collection of self-deprecating jokes, but Dennis was never as popular as Shack, nor as effective a pitchman.

Don Cherry, the broadcaster who famously played but a single NHL game, appeals to a similar demographic as Shack, though Cherry presents himself as a dandy and a peacock. Shack with his black cowboy hat and waxed mustache, not to mention a general disheveled appearance, including a soiled Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins T-shirt on a 1997 book tour, always looked and sounded like he was coming off a bender.

Cherry made a fortune from his series of Don Cherry’s Rock’em, Sock’em Hockey tapes of fights and bodychecks, while the players who endured the pain and the brain injuries earned nothing, a transaction that looks worse with every passing season and each chronic traumatic encephalopathy death.

Cherry also generated a long list of political enemies (gays, Finns, women, Russians, bicyclists, immigrants, Quebecers, “left-wing kooks,” Sidney Crosby, and three former NHL enforcers whom he called “pukes” for connecting their retirement struggles to the physical and mental hardship of their playing days). When his time comes, he will not be universally mourned.

These days, players make too much money to belong to the hoi polloi. Until the 1970s, NHL players earned so little they needed summer jobs. They lived amongst us, rode the bus and subway, could be spotted at nearby restaurants after the game. Not to begrudge them their salaries, but today’s players are far more likely to be found living in McMansions in gated communities in Phoenix than in a walk-up apartment among other working stiffs. It has become an elite suburban and collegiate sport, which certainly heralds a better future for today’s players than that endured by Shack and his generation.

His father, Bill Shack, emigrated to Canada from Ukraine in 1922, eventually making his way to Sudbury, Ont., and onto the Inco payroll at the underground nickel mine at Copper Cliff. He started in the converter building before moved up to the crane cab. In 1932, he married Lena Tataryn, the daughter of a Ukrainian immigrant who worked as an underground driller. The couple soon had a daughter, Mary, and, on Feb. 11, 1937, a son, whom they named Edward Steven Phillip Shack.

The boy did poorly in school. “The teachers always put me in the back row,” he said. Years later, asked how far he went in school, he would deadpan, “About three miles.” It was said he had no more than a Grade 3 education. He likely had an undiagnosed learning disorder.

Shack could write his signature in a looping hand with an unsteady “#23” to indicate his Leafs’ sweater number. When he was asked to autograph the 1997 biography Clear the Track, written by Ross Brewitt, he would have others write in the inscription and then he would sign.

“The book,” he told an audience at the time at Bolen Books in Victoria in a voice as loud and heavy as his wrist shot, “I haven’t read it, but a lot of people who have said it is quite funny, and serious in parts.”

The oft-told tale of one of hockey’s most beloved characters features him being taunted by opponents for his lack of literacy. Infuriated, he skates through the defence and slashes the puck behind the rival goalie, before slowly skating past the rival bench. “Goal,” he declares. “G-O-A-L. Goal.”

Young Shack was trained as an apprentice butcher before turning his attention to hockey, figuring he could land a job anywhere a hunk of meat needed carving. He spent five seasons in junior hockey with the Guelph (Ont.) Biltmore Mad Hatters, leading the Ontario Hockey Association in assists in his final season. When not on the ice, he worked on a coal truck and at a local butcher shop.

He turned professional with the Providence Reds and, after a season, was trying out for the parent New York Rangers. In an exhibition game at Niagara Falls, Ont., he engaged in a stick-swinging duel with Zeidel, who was with the Hershey Bears. Shack slashed his rival’s head, opening a gash that needed 10 stitches to close. The referee ruled it was a deliberate attempt to injure and kicked Shack out of the game. Not long after, the two pugilists met in street clothes under the stands and began to fight again. Spectators prevented police from interfering. At the end of the battle royale, both combatants were arrested.

Shack was freed on $100 bail and was eventually acquitted of disturbing the peace, while Zeidel and a teammate were each fined $237.50 for assaulting a police officer. It would not be Shack’s only brush with the law.

The donnybrook didn’t hurt Shack’s reputation, as the Rangers found a spot for the rookie on the roster. His blond hair cut to a crewcut trim, he was described as a White Tornado and his coach said of him, “If (Niagara) Falls is one of the seven wonders of the world, we’ve got the eighth in Eddie Shack.” The same coach later benched Shack for so long the forward was described as the Lone Ranger.

After three seasons in which he seemed to spend more time in the penalty box than on the ice, Shack was traded to Toronto. The Leafs won the championship in his first three full seasons with the club and Shack stood out as a character, a remarkable achievement on a team filled with popular athletes, including Red Kelly, who was also a member of Parliament.

In February 1966, Shack went from popular player to cultural phenomenon. The previous winter, the seasonal novelty song “Honky (the Christmas) Goose,” sung by Toronto goalie Johnny Bower and his son and friends, enjoyed modest success. Brian McFarlane, a hockey broadcaster and writer (as well as the son of Leslie McFarlane, who ghostwrote the first Hardy Boy novels as Franklin W. Dixon), decided to write a song about Shack. Eddie gave his okay. The younger McFarlane wrote the lyrics:

“Clear the track,

Here comes Shack.

He knocks ’em down,

He gives ’em a whack.

He can score goals,

He’s found the knack.

Eddie, Eddie Shack.”

His brother-in-law wrote the music and they paid a group of teenagers $500 to record the tune. It was played on Hockey Night in Canada and “Clear the Track, Here Comes Shack” by the Secrets quickly climbed the charts of CHUM, Toronto’s top rock station. It topped the chart for two weeks, overtaking the Beatles and Petula Clark before being displaced by Nancy Sinatra and then the Beatles, again.

The record generated friction between McFarlane and Shack, as the player for decades afterwards demanded royalties from a recording that never made any. The band members, who leaned more towards coffeeshop folk than pop, changed their name to the Quiet Jungle to avoid the notoriety, but were unable to repeat their chart success. Leader singer Doug Rankine died two years ago.

The song opened the gates to Shackmania. The winger was featured on the cover of Star Weekly in 1966 as a “swashbuckling hero” and inside Maclean’s magazine for his recipe for arroz con pollo. Shack also appeared in a bizarre 1966 television skit on CBC TV’s the Umbrella program in a segment titled, “Eddie Shack’s Nightmare.” The hockey player’s surrealistic dream included a jazz band, a brass bed, custard pies and a model in a gingham bikini, a cameo which launched the career of one Barbara Amiel.

In 1969, by which time Shack had been dispatched to Boston, the oddball singer Tiny Tim, a hockey fan, visited Maple Leaf Gardens for a charity game at the height of fame as a singer of “Tip-toe Thru’ the Tulips With Me.” He borrowed Pat Quinn’s no. 23 sweater, because it had been the number worn by Mr. Shack.

Shack kicked around the NHL with the Los Angeles Kings, Buffalo Sabres and Pittsburgh Penguins before being sold back to the Leafs in 1973. He was no longer an effective player, but the return to Toronto allowed him to convert his popularity into an endorsement bonanza.

Shack was Everyman, a likeable, buffoonish former player who made fun of his impressive proboscis. “I’ve got a nose for value,” he says in a 30-second spot for the discount Pop Shoppe. He blew his honking schnozz into tissue and he put on boxing gloves to lay a licking on a Ruff’n Reddi garbage bag (before kicking it open in frustration in the commercial’s punchline). He sold water softener. In a commercial for a motel chain, a suitcase rests on a bed as fans can be heard chanting, “Shaq! Shaq!” The suitcase opens and out pops Shack. “What did you expect? A million-dollar basketball player?” he says. Then he takes a puck to the face. “Wow, that just about got me!”

A razor-blade company ran a $10,000 contest for the right to shave Shack’s famous handlebar mustache.

“I do the commercial my way,” he once said. “They bring me the script, then I do them the way I want, because I really don’t want to act.”

His demand was such that he also appeared on countless television shows. He was a fishing guest at Scuttlebutt Lodge on The Red Fisher Show and he appeared with the folk singer Valdy as a special guest star on the debut of John Allan Cameron’s eponymous variety show. He made a cameo during a broadcast of Murray McLauchlan: On the Boulevard, with guest star folksinger Bruce Cockburn and Howie Meeker delivering a comically histrionic play-by-play commentary on the first half of the show. On Jan. 6, 1981, he joined in a traditional Ukrainian Christmas Eve celebration on the The Bob McLean Show. Shack was a one-man CanCon fulfilment.

He ran a hockey school, built a golf course, maintained a Christmas tree business he had started in the 1960s. In the mid-1990s, he moved into franchising. A chain of hockey-themed Eddie Shack Donuts got a lot of attention, as he lined up former players Bower, Frank Mahovlich and Andy Bathgate, as well as Lori Horton, the widow of Tim Horton, Shack’s former teammate whose name graced Canada’s most-successful doughnut franchise.

Shack also opened two outlets of what was supposed to be a chain of Hill Billy Shack Saloons. The menu included newspaper clippings of the player’s exploits, while the courses were described as periods in a hockey game. Appetizers were “game warmups.” On the front of the menu, it read: “This menu was stolen.”

Those business franchises did about as well as hockey’s hapless Oakland Seals franchise.

He was so popular that even reports of off-colour speeches or otherwise reprehensible behaviour barely dented his reputation. Shack, driving a dune buggy, once led police on a high-speed chase through the streets of Toronto. He was fined just $175 and the story only generated a small item in the newspapers, almost all of which seemed to have some play on “clear the track” in the headline.

People were invested in seeing Shack as an honest, blue-collar character who made the most of limited talents. He was an immigrant miner’s son squeezing nickels to make a paycheque last.

Who, today, would believe a player making the NHL minimum salary of $700,000 is shopping around for discount cola? ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: