- Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination

- Dutton (2019)

He gave us the word “nerd,” and a host of memorably subversive characters: Horton, Yertle, the Grinch, the Cat in the Hat, and Sam-I-Am. In many ways, Dr. Seuss made us all.

But few know that Theodor Seuss Geisel had also been a major force in American advertising, an anti-Hitler political cartoonist, an accomplished filmmaker during the Second World War — and a publisher who changed education.

Brian Jay Jones has written what seems likely to be the definitive biography of Geisel, and firmly establishes him as a major force in 20th-century American culture. It was a remarkable outcome for a young man who graduated from college with an English major and no idea what to do with his life.

Ted Geisel was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1904, the son of a German-immigrant family that made a fortune in brewing and real estate. He enjoyed the privileges of prosperity: an education at Dartmouth (where he ignored classes and focused on writing cartoons and gags for the campus humour magazine), and a couple of years in Europe. While studying at Oxford, he met Helen Marion Palmer. She was also American, five years older, and they soon became a couple.

Palmer was smart and opinionated, traits Geisel admired. “You’re crazy to be a professor,” she told him. “What you really want to do is draw.”

Her influence gave him a purpose he’d lacked. Eventually they returned to the U.S., where Geisel settled in New York City and began a career as a freelance cartoonist and humorist. It wasn’t easy, but he managed to sell cartoons to magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and especially to Judge, a humour magazine that was the print equivalent of today’s Onion. The pay wasn’t great, but it was enough to let him and Palmer get married.

Geisel began signing his cartoons and written pieces “Dr. Seuss” (using his mother’s maiden name), and they were archaic by our standards — wife jokes, booze jokes — but they paid the rent.

‘Quick, Henry! The Flit!’

One cartoon paid for a lot more: a knight confronting a small dragon complains, “Darn it all, another dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit” (a popular insecticide). The ad agency that handled the Flit account noted it and recruited him to do a series of Flit cartoons.

Geisel turned out to be a marketing genius. He invented “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” — a slogan that lasted for years.

But he was interested in more than advertising; in the mid-1930s he published his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street! It and the next few books did reasonably well, but none really took off.

Then the war arrived, and Geisel found himself in Hollywood, working for director Frank Capra on short information and propaganda films for GIs. After the war, Geisel returned to his “brat books.” They did well, and for a decade he built his reputation as a witty writer and illustrator. But he still seemed unable to create a breakout book, one so successful that he could afford to drop the occasional advertising gig.

The breakout came in 1957, after years of widespread criticism of the way children were being taught to read. The “Dick and Jane” books (which I remember well) were insipid: “Look, Jane! Look at Spot. Look, look!” Parents and teachers alike were impatient with their kids’ poor reading skills.

When an education publisher asked Geisel to do a primer that kids would actually enjoy reading, he agreed. The deal would include a commercial edition with his regular publisher, Random House.

Catch-225

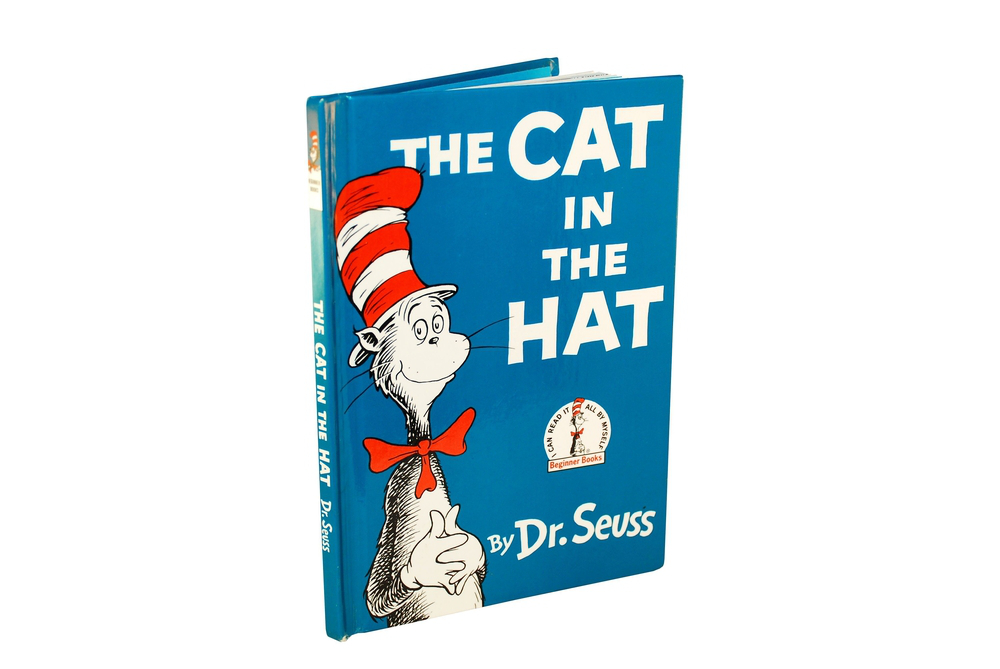

But there was a catch: the story had to be told with a vocabulary of just 350 words that first-graders would know — and preferably just 225. That nearly killed the deal. Geisel fussed with the project for years while also producing his regular books, but seemed to get nowhere. Then, going through the damn list one more time he saw two words: Cat. Hat.

The Cat in the Hat still took over a year. It came out in April 1957 and almost at once started selling a thousand copies per day — and over a million copies in three years. For Random House, the commercial edition was a gold mine; teachers, ironically, were hesitant to put it in the hands of their pupils, so the school edition was a relative failure.

Random House publisher Bennett Cerf considered Geisel the only genius among his authors, and made him an irresistible offer: become the publisher of children’s books with his own Random House imprint. Geisel and Helen became two of the imprint’s directors, with Cerf’s wife the third. It was a turbulent partnership, but it found and developed a host of new children’s writers like the Berenstains.

Somehow an odd young man, who liked to draw impossible animals instead of taking notes in lectures, had become a major force not just in North American education, but also in our culture. While teachers paused to think about who their students really were, and how to teach them, the children themselves learned more from Horton and the Lorax and the Grinch than they ever learned from anyone else.

Jones has deeply researched his subject, and shows Geisel warts and all, making dumb misogynist and racist jokes, but outgrowing them with age. He shows us Helen Geisel as a complex and talented woman, whom he deeply loved and cared for. But he eventually also fell in love with a friend’s wife, and married after Helen killed herself.

I remember Dick and Jane, but I remember far more vividly the 500 hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, and the amazing parade down Mulberry Street. When I think about the bestselling adult writers of the 1940s and 50s, they seem quaint and deservedly forgotten. Even Norman Mailer, for all his notoriety, has faded back into the university library stacks.

But Theodor Geisel inspired the imaginations of millions of children. His images changed their view of the world, and his verses and ideas gave them permission to invent their own. As threatening and uncertain as our world may seem, it would be far worse if Dr. Seuss hadn’t told us, “A person’s a person, no matter how small.” ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: