- What's Happened to Politics?

- Simon & Schuster (2015)

- The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin

- Oxford University Press (2011)

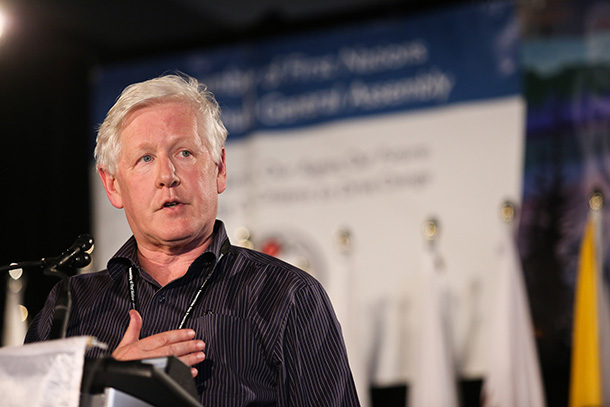

Judging from the one time I met him, Bob Rae is a genuinely nice guy -- friendly, a good listener, an articulate speaker whether to a group or to individuals.

On TV, he was one of a very few politicians who could think on their feet. Before leaving Parliament he could speak eloquently and off the cuff in question period, without needing his talking points written out for him on a piece of paper. Reporters interviewing him got good quotes, flashes of wit, and a sly grin that told us what he thought about the nonsense passing for political discourse in Canada.

Now out of politics, Rae evidently feels even freer to say what he thinks about such discourse, and his short new book does not disappoint. In a clear and conversational style he outlines what's happened in Canadian politics, especially in five key areas: leadership, policy, aboriginal issues, democracy, and our place in the world.

Without rehashing all his points, it's enough to say he generally gets these issues right. "Today," he writes, "the electorate is sliced, diced, dissected and divided to an extent unimaginable even 15 years ago." No argument.

"There is a lot of evidence to suggest that driving turnout down, 'depressing the vote,' is just what conservative parties want." No argument.

"A momentous change occurred, from economies and societies based on hierarchy and conformity to those composed of people who insisted that their voices be heard and that authority be made accountable and transparent." Again, no argument.

But however readable and insightful his analysis, Rae's argument is one such truism after another. He says very little about the key reason for what's happened to politics (and especially to his own Liberal Party): the hierarchical, conformist Conservative Party of Canada and its leader, Stephen Harper.

This is surprising, because for 10 years the political thought and actions of Stephen Harper have inspired countless books and articles among our commentariat -- the genre I call Harperlit. These provide more detailed descriptions of what Harper has done to Canadian politics than Rae offers, but no one has done serious analysis of Harper's motives.

Pop psychology but no analysis

Instead we get pop-psychology explanations (he doesn't like taking orders from anyone) and explorations of his religious beliefs. Then it's back into the grim litany of his sins and his skill in committing them.

By chance, I stumbled across Corey Robin's 2011 book The Reactionary Mind just as I was finishing Rae's. Robin is an American political scholar, specializing in the philosophy and history of conservatism since the French Revolution; his book is a collection of essays and reviews on aspects of that philosophy. His focus is on the U.S. and Europe, and he doesn't mention Harper or Canada at all.

But in his introduction, where he ties together the themes of his essays, Robin writes a ferocious polemic on conservatism that is also a devastating portrait of Stephen Harper as the heir to two centuries of conservative thought and action -- better said, reaction.

Conservative = reactionary

Robin explicitly uses "conservative," "reactionary," and "counterrevolutionary" interchangeably and traces them to the shock of the French Revolution on the upper classes; ever since, he says, they have resisted the lower classes "violently and nonviolently, legally and illegally, overtly and covertly." The upper classes believed in a hierarchical society of those who should rule (themselves) and those who should obey. The lower classes believed in an egalitarian society where all should choose their rulers.

Conservatism, Robin argues, "is a meditation on -- and theoretical rendition of -- the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back."

Conservatives see themselves as literally the natural governing party, from the household to the throne: the husband rules in his own home, the employer in his workplace, and the ruler in his palace or parliament. For the wife and children to demand a say, for the workers to bargain collectively, for the voters and their institutions to exercise real power, real agency, is to threaten the natural order.

"Conservatism," says Robin, "is the theoretical voice of this animus against the agency of the subordinate classes." The conservative wants freedom and equality for himself and his class, but extending them to the subordinate classes means a loss of his own freedom.

And he sees that loss in very personal terms. "Every great political blast," Robin says, "... is set off by a private fuse: the contest for rights and standing in the family, the factory, and the field." Think of Rosa Parks refusing to move to the back of the bus, or Mohammed Bouazizi setting himself on fire in Tunisia and igniting the Arab Spring.

What follows such private actions is a terrible loss for the rulers. "The priority of conservative political argument," Robin says, "has been the maintenance of private regimes of power -- even at the cost of the strength and integrity of the state."

Conservative ≠ stupid

And conservatives are far from stupid people. Robin says: "Liberal writers have always portrayed right-wing politics as an emotional swamp rather than a movement of considered opinion." But conservative political thought is extensive and intensive, and no mere yearning for the good old days. If a hierarchical power elite fails to maintain itself, conservatives treat it with contempt. As Robin observes, conservatives study the left's successes and adopt its tactics.

Admiring the energy and ruthlessness of the French Revolution, says Robin, conservatives quickly absorbed its radicalism: "If he is to preserve what he values, the conservative must declare war against the culture as it is."

While he still wants a hierarchical society, the conservative no longer supports the old aristocratic regime; simply by being overthrown, it's disqualified itself. Instead he seeks his ruler in the meritocracy, those who have fought their way up against the left. Such a ruler is a romantic figure, an Ayn Rand capitalist hero imposing his own will and vision on his nation and beyond.

The capitalist, Robin says, is a warrior showing "daring, vision, and an aptitude for violence and violation" that make him not only rich but a legitimate "ruler of men." But such rulers see themselves under constant threat from the subordinate classes: "Conservatism is about power besieged and power protected."

In a country with the trappings of democracy, how does conservatism win elections? This question has maddened leftist thinkers, who can't believe workers would vote for their exploiters.

Sometimes race is the key. American slaveowners gained the support of poor whites by making them members of a white aristocracy over the blacks. (Southern states even offered tax breaks to enable such whites to buy their own slaves.) Since Richard Nixon, the Republican Party has controlled the South by discreetly backing white supremacy.

Millionaires in waiting

More often, such support is won by making working people think they're on the verge of becoming millionaires themselves, whether by hard work or a lottery ticket. They don't want to hear the hard facts about inequality and the lack of social mobility in North America.

If you have read this far in my summary of Corey Robin's analysis, you have likely applied his findings to Stephen Harper. At some point in his youth, he had his "Bouazizi moment," when the status quo became impossible. As a son of the oil industry, he'd been robbed of his inheritance by Pierre Trudeau's National Energy Program. He found Peter Lougheed's old Progressive Conservatives inadequate, and burned through them, the Reform Party, and the Canadian Alliance before launching his hostile takeover of the moribund federal Tories.

For all that he's enjoyed power for nine years, he has been constantly threatened (often by response to his own radical actions). The subordinate classes want their freedom, but whatever he gives them will be a loss of his own. So he's declared war on his own culture, the liberal Canada that brought him up and educated him.

Harper's success in that war (if not in Syria or Afghanistan) has made him a romantic reactionary hero to the Canadian right. But like the economy under his watch, it is a fragile success, likely to disintegrate if the subordinate classes push him out. He must be ready to frustrate them "violently and nonviolently, legally and illegally, overtly and covertly."

Stephen Harper is not a one-off. The western nations have dealt with his reactionary kind not just since the French Revolution, but since the Peloponnesian War over 2,000 years ago, when democratic states like Athens fought against oligarchic states like Sparta (Sparta won). Harper is just our own bush-league oligarch, and he won't be the last.

Modern reactionaries including Harper have studied the left while the left laughed at them. Even 40 years after the rise of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, the left -- even the "moderate" centre-left like Bob Rae -- doesn't understand that our reactionary fellow Canadians have always despised us as sincerely as al-Qaida and ISIS do.

So it's not enough to wisecrack about our despisers as Bob Rae does, with flashing wit and a sly grin. We need to understand these guys as well as they understand us. Rae is a very nice guy, but in Stephen Harper's Canada, nice guys finish last. ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: