- Thrown: British Columbia's Apprentices of Bernard Leach and their Contemporaries

- Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (2011)

In 1989, when curator Scott Watson took over the helm of University of British Columbia's Fine Arts Gallery, he was given this stark proviso: "Just don't show any pots!" Such was the thinking as the 20th century drew to a close, with the arts establishment disenchanted with craft and its associated activities.

In a recent interview at the now-renamed Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Watson pondered the twists and turns of pottery's reputation within the arts. Until 1980, he observed, every notable art gallery and museum in Canada had some sort of pottery exhibition each year. The Vancouver Art Gallery's last pottery show opened in 1978: a five-week-long exhibition of the work of Wayne Ngan. By that time, the cleft between the concepts of "art" and "craft" was starting to widen.

"There's still a belief that something that has a function can't be art," says Watson. But hand-thrown pots have a visceral appeal to people — especially artists — who feel that the present society has strayed too far from our natural rhythms, he says. "The mark of irregularity is the mark of individuality, the mark of something unique."

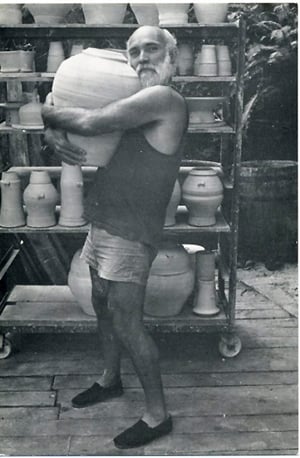

Watson is co-author of a significant new book on British Columbia pottery from the 1960s and '70s. Compiled of essays by frontline potters and scholars, Thrown: British Columbia's Apprentices of Bernard Leach and their Contemporaries argues for pottery's seminal importance as an art and, for that matter, a philosophy. Published by the Belkin, Thrown is loosely based on a 2004 exhibition mounted by the gallery. The exhibition and now the book make the case for re-establishing potters as key players in B.C. cultural history.

Thrown includes essays by or about many of the major talents of the day, including Wayne Ngan, John Reeve, Charmian Johnson, Tam Irving, Glenn Lewis and Michael Henry. They formed part of an iconoclastic generation of artists who were not automatically impressed by tradition and pedigree.

Most made overseas pilgrimages to the workshop of British master potter Bernard Leach, in St. Ives, Cornwall. Leach's Canadian apprentices then returned to the west coast to ignite the local pottery scene.

Respect for the ordinary

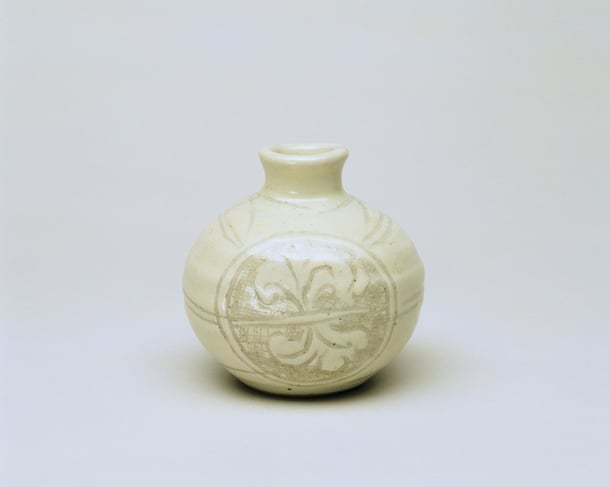

Leach promulgated the idea of the "ethical pot" — beautiful but also useable kitchenware — as opposed to the "fine art pot," created with the sole intention to be admired rather than used. But this approach, noble and logical though it might be, might have have actually kept potters out of the cultural canon. The art industry, to be sure, is larded with pretension; useful and widely available domestic objects don't quite fit the mythology. "Part of why ceramics have been ignored in the world is that they're inexpensive," says Vancouver potter and contributing essayist Nora Vaillant. "Why doesn't this culture respect the 'ordinary'?"

As Vaillant relays in the book, craft artists and potters were emblematic of the 1960s and '70s counterculture movement: the handmade has the power to change the world. The mugs and jars issuing from potters' wheels could be used to preserve and store food, making them the perfect object for the anti-consumer back-to-the-land movement.

Potters have been so marginalized in recent decades that few people are now aware of their contribution to our cultural identity. Before the pottery movement, the most vaunted dinnerware at west coast tables was Rosenthal or Wedgwood china. But these delicately patterned cups and saucers were colonial byproducts, an expression of British formality and politesse. The organic shapes of the regional potters' mugs and bowls evoke the coastal mountains and provide a much more authentic expression of regional culture, argues Vaillant.

"In the 1960s, Vancouver had a really happening art scene, and pottery was a major part of it," says Vaillant. Back then, the art community exhibited an openness to every medium, including pottery.

This countercultural appeal was not just a matter of fashion but part of humanity's visceral response to its own near-obliteration in the last century's military conflicts, suggests Watson in his own essay. Homicidal ideology was followed by the postwar period's soulless materialism and technological onslaught. "Within this context," writes Watson, "pots were part of an attempt to recover a world of things essentially and universally 'human.'"

Thrown off the radar

The terse word of the book's main title refers to the precise act of making a pot: you literally throw it on the pottery wheel. But as Watson writes in the preface, the word also evokes philosopher Martin Heidegger's concept of human existence as the state of being "thrown" into the world, with no past or future beyond our allotted life span.

You might also consider it an analogy to what has happened to British Columbia's acclaimed potters in the 30 years since the apogee of their success. They've fallen off the canon. The essays in Thrown elaborate on the tortuous route and undeserved obscurity that has befallen ceramic artists.

Potter Charmian Johnson, for instance, is a superb talent who has been unjustly ignored, writes contributing essayist Glenn Allison: "In Canada, the term 'folk craft' has come to have a pejorative connation," misconstrued as either "quaint work of the unschooled" or mass-produced kitsch that you'd find at souvenir shops.

Allison and many of his colleagues prefer the more nuanced Japanese term mingei — "crafts made for the people by the people: everyday, necessary items as opposed to the rare, costly and idiosyncratic," he writes.

Our more renowned midcentury-modernist designers and architects have also been long inspired by their peers in pottery. B.C. Binning and Arthur Erickson, among others, were huge admirers and collectors of famed Japanese potter Shoji Hamada. (Erickson's estate recently sold two gorgeous Hamada vases.) In Fred Hollingsworth's landmark North Vancouver house, the entrance to the living room is scrimmed with a beautiful curtain of handmade clay beads fired by Hornby Island potter Chris Thom. And her erstwhile husband — architect Ron Thom — was a huge pottery fan, and consigned John Reeve to do the ceramics for Toronto's acclaimed Massey College.

Contemporary Vancouver artists such as Damian Moppett, Rodney Graham and Brian Jungen also collect pottery. Jungen confirmed in an email that his large collection includes more than a dozen pieces made by Ngan and fellow B.C. potters Gordon Hutchens and Heinz Laffin. "I make sculpture and so I have always admired the hand-made skill and unique forms from these potters," Jungen told The Tyee.

Watson himself is the proud owner of a set of Michael Henry dinnerware: "I use the stuff I buy — which is insane," allows Watson. "I'm driving a car that's worth less than the plate I serve dinner on." ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Do not:

Do: