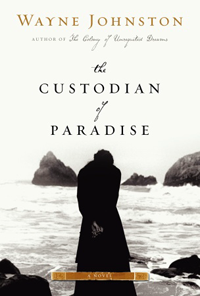

- The Custodian of Paradise

- Knopf Canada (2006)

- Bookstore Finder

For the last seven or eight years, Wayne Johnston has set about establishing himself as one of the great myth makers of Canadian fiction. In 1999, the Newfoundland-born author (who now lives in Toronto) created a fictionalized founding mythology for his home province. The Colony of Unrequited Dreams tracked the life of Joey Smallwood, the physically tiny political giant who brought Newfoundland into confederation.

Big, funny and breathtakingly well-written, Johnston's fifth novel was a huge critical and commercial success. His follow up, The Navigator of New York, again spun a fictional story around actual facts.

For his seventh novel, Johnston -- who appears at two events this week at the Vancouver International Writers Festival -- returns to the world he created in The Colony of Unrequited Dreams. Sheilagh Fielding first appeared in that book as Smallwood's sometime muse, would-be lover and general foil. A six-foot, three-inch alcoholic daughter of the quality, Fielding was everything Smallwood -- small, sober and from the wrong end of St. John's -- was not. Johnston's new book puts Fielding front and centre.

'Among Canada's best'

The Custodian of Paradise is an excellent novel. Tightly written and well paced, it never feels chubby even at more than 500 pages. What Johnston manages -- and it's no small feat -- is to combine the tension of a thriller with a complexity of characterization that rivals Mordecai Richler's or Carol Shields' as among Canada's best.

The plot is a pretty simple construction. The book begins where you know it will end, on Loreburn, an abandoned island off the coast of Newfoundland. The central question of the story is how, and why, Fielding ends up on that rock.

The how is answered in the first line of the first page: "A clause in my mother's will tersely stipulated: 'I leave to Sheilagh Fielding, the only child of my first marriage, the sum of three thousand dollars.'"

That $3,000, we soon find out, funds Fielding's excursion. The why, on the other hand, takes a little longer.

Over the next 509 pages a series of tragedies -- beginning with abandonment by her mother and ending with the death of her only son -- burden Fielding. With each successive blow she becomes more and more the character we meet in Chapter 1, a crippled recluse with two trunks full of scotch, running from her single room home in a St. John's whorehouse.

CanLit's compelling misery

Johnston keeps the action flowing with a varied and punchy sentence structure, where each long thought is punctuated with a short jab. His sentences don't have Michael Ondaatje's poetic elegance, but I don't think his story would work if they did. Johnston's strength as a writer is his ability to keep you reading. I even found The Navigator of New York, a book I didn't really like, hard to put down. In a Johnston book, you always feel like he's taking you somewhere. And his attractive, accessible sentences mean you're going to enjoy the trip.

By focusing so narrowly on Fielding and her admittedly terribly life, though, Johnston risked following the now too-familiar path to CanLit fame: take a character, preferably a maritime rube or big city immigrant; apply shit for 500 pages; collect your major book prize. See MacLeod, Alistair or Mistry, Rohinton for examples. What redeems The Custodian of Paradise is Sheilagh Fielding.

Fielding is Johnston's best, most fully realized character. The dust jacket for the novel boasts that she is "one of the most memorable and beloved characters in Canadian fiction." If that were an exaggeration before Custodian, it won't be for long. If Custodian of Paradise sometimes feels like little more than an extended character sketch, it's because the character deserves it.

Character wins out

The book does sometimes feel slight. On a couple of occasions, big chunks of Fielding's life are dismissed with little more than a sentence. That can be a good thing -- too much detail and the story chokes. But in Custodian I often felt like I was missing something vital. Key relationships in the book seemed to jump fully formed onto the page. The aborted romance between Fielding and Smallwood leaps from vague acquaintance to professional colleague to unrequited love in a series of disconcerting bounds.

It may be that, having already told Smallwood's story in The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Johnston felt comfortable breezing through the details this time around. But I read the Colony almost seven years ago.

Parts of the narrative also feel almost wholly unbelievable. Fielding's Provider, a seven-foot-tall former priest who repeatedly intervenes in her life and may or may not be her real dad, feels like a fairy-tale fantasy. And you spend a good chunk of the book wondering if maybe he is. The novel's noirish, pulply climax too felt a bit forced. Johnston resolves the novel's tension with writerly aplomb, but the details, which I won't spoil, seem a little far-fetched.

More than anything, though, what I missed in The Custodian of Paradise was a little brevity. Johnston is hilarious when he wants to be. His fourth book, The Divine Ryans, might be my favourite Canadian comedic novel. The dialogue in The Custodian of Paradise is witty, but the story is unrelentingly morose.

Still, in Fielding, Johnston has created a giant of a character. The Custodian of Paradise assures his place among elite Canadian novelists. The only question is, what's next?

Richard Warnica is a senior editor at The Tyee.

Wayne Johnston joins six other writers for Grand Openings, Oct. 18 at 8:30 at Performance Works. On Oct. 19, he gets the PTC Studio stage to himself at 8 p.m. Most Vancouver International Writers Festival events take place on Granville Island. For complete program details, click here. ![]()