The ink had barely dried on council's new development plan for the Downtown Eastside when residents took to the streets in protest. The $1-billion initiative, which would see the gradual encroachment of market housing into the low-income community, is already fuelling the inevitable worries about displacement and the potential transformation of Vancouver's oldest neighbourhood.

But as Jason Vanderhill, curator of "Vancouver Imagined: The Way We Weren't" (which runs until May 11 at the Museum of Vancouver) explains, the plan is hardly the first in city history with such broad, transformative possibility. There are many others which could have altered the character of the city in ways equally as significant.

There's only one crucial difference: they never happened.

To prove his point, Vanderhill, who assembled the collection of drawings, photographs, and scale models during ongoing research for his website, Illustrated Vancouver, has created an impressive collection of developments that never were -- everything from alternate ports to aborted waterfront developments. Some were never considered. Others faced vociferous public opposition. At a time when real estate is on everyone's lips, here's a collection from the city's undeveloped past.

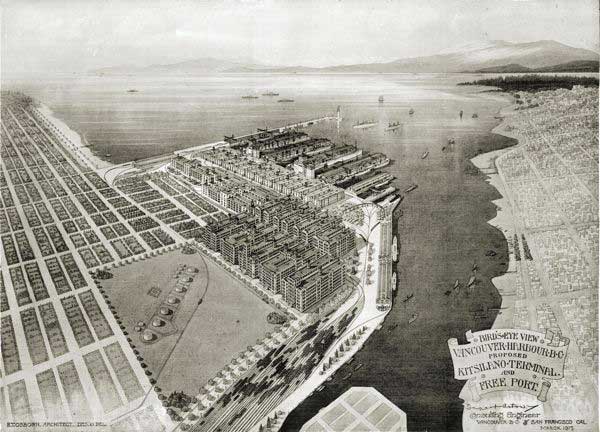

1. The Kitsilano Port

Lovingly rendered in March of 1917, the Kitsilano Port and the buildings that surrounded it were the brainchild of England-born designer Edward Osborn, at the time a delineator for several well-known American architectural firms. Intricate watercolour images were Osborn's trademarks, and although he was occasionally commissioned for specific commercial projects, the Kitsilano Terminal and Free Port appears to have been undertaken entirely on his own initiative.

"It's all about this young, aspiring architect/designer/illustrator trying to get his name out, to get recognition," explains Vanderhill. "This is how people did branding: coming up with these wild ideas, whether or not they even had a client. The drawing itself says: architect, designer, developer. He was really thinking ambitiously, saying: 'Look what I can do!'"

While a port in Kitsilano may seem ludicrous now, it was much less farfetched in the Vancouver of the early 1900s. Before it was dredged for shipping, the First Narrows was too shallow to allow passage of bigger ships, which were effectively cut off from the city's inner harbour. Thus the Kitsilano location, essentially the closest piece of land to both Burrard Inlet and False Creek, would have remained a viable possibility if not a desirable one. All the same, the Kitsilano Terminal doesn't appear to have received any attention in city council -- a fate shared by a number of Osborn designs. He completed similarly flamboyant drawings, including a "Natatorium" (aquatic centre) and a hotel intended for English Bay, but neither were ever built.

Vanderhill has found only one of Osborn's buildings still standing -- a hotel south of the border that is now official campus housing for university students.

"It's kind of tragic," Vanderhill laments, "because he had all these really flamboyant ideas, and they didn't really get fulfilled. A lot of them were perfectly rendered in pencil, but perhaps that speaks to his abilities. He was really good at hunkering down and illustrating, but his ability to network and actually get things built was maybe lacking."

The land for the proposed port is now part of Vanier Park.

2. A Burrard Street city hall

In January 1936, in the midst of the Great Depression, Mayor Gerry McGeer broke ground at the site of Vancouver's new city hall on the land at 12th and Cambie then known as Strathcona Park.

But the building, along with an elaborate "Civic Complex" which would have included a courthouse, art gallery, library, and auditorium, was briefly proposed for a totally different location: the foot of Burrard Street. In 1928, the city commissioned artist John Tanqueray to envision the development, which would have extended all the way to Beach Avenue, overlooking the (yet-to-be-constructed) Burrard Street Bridge.

"This is probably one of the best-known grand schemes," Vanderhill notes. "And it's also more significant because it's something the city actually commissioned… It was at going to be at the foot of Burrard Street, which, at that time, would have all been residential. It would have been hugely destructive to that neighbourhood. We don't know who lived there, and how vocal they would have been about changes like that. It would have turned it into a different neighbourhood."

This wasn't the only proposed site for the new city hall. The three-man selection committee appointed by Mayor McGeer also suggested the south side of Victory Square before settling on its current location, marking the first time a major Canadian city chose to place its city hall outside the downtown core. Despite the economic realities of the Great Depression, McGeer managed to raise enough funds (often on his own time) to make the building a reality, though the other proposed amenities fell by the wayside.

3. The Four Seasons at Stanley Park

"Study this bold and imaginative plan of Harbour Park/Four Seasons development with an open mind," pleaded an ad in the Feb. 20, 1971 edition of the Vancouver Sun.

At the time, developer Harbour Park had reason to be defensive; its plan was to take the land at what is now Devonian Harbour Park, at the entrance to Stanley Park, and transform it into a $40-million residential/commercial complex set to include six apartment buildings and a Four Seasons Hotel. The plan also called for 20 town homes, 2,000 spaces of underground parking, lush retail stores, and, in perhaps its only rational moment, a seaside promenade similar to the current seawall.

"I sincerely feel that the type of development that we are proposing will be aesthetically beneficial to the area and Stanley Park in particular," Four Seasons President Isadore Sharp wrote in a 1970 letter. "Our philosophy of development is a true integration of building and landscaped areas. We go to great detail to assure that the natural landscaping becomes a most important part of the development."

Vancouverites were outraged.

The development was opposed by a number of community organizations, including the West End Ratepayers Association, the Local Council of Women and the Grandview Ratepayers Association. The Park Board too was vehemently against the plan, with board chair George Puil even writing to the federal government for help.

"All seven members of the park board have consistently opposed the development scheme on the grounds that huge concrete structures next to Stanley Park would be totally out of scale, would block people's view of the park and waterfront, and would create a traffic hazard," Puil wrote, in the fall of 1970, "and further, would be a violation of the city's tradition of preserving its waterfront for public use and enjoyment."

Locally, the project polarized public opinion; a civic plebiscite on the issue was split nearly 50-50, and in May 1971, a group of community protestors occupied the site, put up shacks, and declared it "All Seasons Park." The structures and their occupants would remain for almost a year, as both Isadore Sharp and Mayor Tom Campbell (who actually went to the All Seasons Park site to gloat in front of community protestors) announced that development would proceed despite local opposition. The project ultimately fell apart in 1972, when approval for a key piece of land deeded to Ottawa failed to materialize. By August, in the face of dwindling public support, Four Seasons quietly withdrew from the project.

"Interesting that a city council, on the scene, was prepared to let the deal go through and that it took a government 2,500 miles away to kill it," concluded Sun columnist Allan Fotheringham. "Who says public opinion doesn't work?"

4. Christ Church, Arthur Ericksonized

In May 1971, the congregation of Christ Church Cathedral voted 72.1 per cent in favour of demolishing the historic building (one of only a handful of pre-1900s structures still in existence), and replacing it with a $7.6-million Arthur Erickson office tower complex known as Cathedral Place. The decision followed a year of serious money woes, and the intention was to use the tower's $112,000 in estimated annual revenues to fund the church's continued operation. It was an unpopular decision, to put it lightly.

"My generation will inherit a city that has no soul," a 16-year-old boy protested at a public meeting. "If you destroy this and replace it with a monument to materialism, you'll be left with an empty meeting place."

Despite having been approved by the Archdiocese in New Westminster, the project remained in stasis for close to three years, and drew considerable attention from the local papers, including vocal opposition from popular Sun columnist Fotheringham. Finally, after years of debate, the city denied Cathedral Place a development permit. In the months to follow, the Christ Church congregation managed to save themselves after brokering a $300,000 annual, 100-year deal with a multinational developer, whom the city rewarded with relaxed building-height restrictions.

In 1976, the Cathedral was designated a Class A Heritage Site, ending any further threats to its destruction. (An unrelated Cathedral Place was opened right next door in 1991). A scale model of the proposed office tower development still exists in the Museum of Vancouver's permanent collection.

"In reality, there are some innovative things happening at the street level, even as a pedestrian," Vanderhill explains. "You've got an interesting interplay of public space, private space... there's some variety there. It would have been an interesting place to wander around, but at what sacrifice? You're literally knocking down one of the oldest churches in the downtown core."

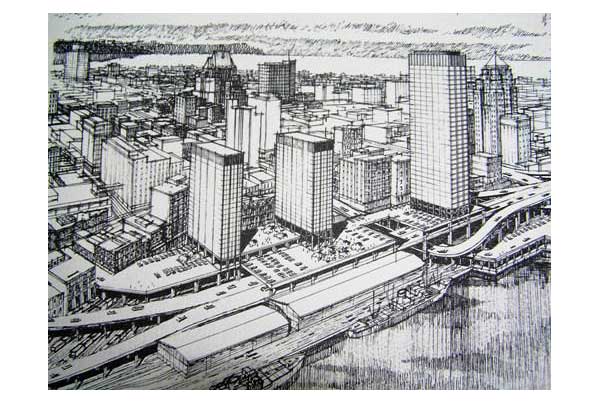

5. The most horrible freeway

The late '60s and early '70s seem to have been the heyday of dumb development ideas, and none was dumber than this $300-million plan to tear up large portions of Strathcona and Chinatown and "revitalize" the waterfront with some office towers connected to an elaborate freeway system.

The site itself would have laid waste to everything between Abbott and Howe Streets (north of Cordova) and Waterfront station, while the proposed freeway system (a distinct entity in talks since the early '60s) was designed as everything from an ocean parkway across English Bay, to, most horribly, an eight-lane, 10-metre deep trench meant to run from the Burrard Bridge to Stanley Park.

"This is the most commanding position Vancouver has to offer," the Project 200 proposal brochure declares. "The base of Granville Street at the harbour front is the focal centre of the Downtown area. The development would be clearly visible for miles around the harbour area and would be readily identifiable by the public."

The development was backed by Woodward's (which, unsurprisingly, would have had its flagship store on the "revitalized" waterfront), and featured a series of high-rise towers connected by raised pedestrian plazas overlaying the seething mass of auto traffic beneath.

The concept went through some changes during its years in development, including one concept that would have laid waste to the historic Sinclair Centre -- much to the chagrin of city illustrator Andrew Malczewski.

"The city would have asked him, 'What would it look like if we were to demolish the Sinclair Centre and just leave a tower?'" Vanderhill explains. "And so, he drew [it], kind of reluctantly. I've talked to him about it. He said: 'Well, there's one drawing that I wasn't too pleased with. I demolished the Sinclair Centre.'"

Public opposition was considerable, and only one piece of Project 200 was ever built -- now the Pacific News building at 200 Granville Street. Although the popular conception is that community activism spelled the end of Project 200, the reality is mainly disagreements between the federal and provincial governments kept it from materializing -- in particular, a lack of funding for the waterfront freeway.

"Every other American city was doing this," Vanderhill explains. "It was considered necessary to keep your downtown moving. It was all about keeping traffic moving.

It wasn't until voices like Jane Jacobs said a city has a lot more to do with the pedestrian experience than the car experience that the project died, Vanderhill adds. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: