[Editor’s note: Tyee contributing editor Andrew Nikiforuk is the author of two best-selling books on epidemics: The Fourth Horseman and Pandemonium, both published by Penguin Books.]

“It is the microbes who will have the last word.”—Louis Pasteur

In 2016 the Commission on Creating a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future, a U.S. panel of health experts, warned that “the conditions for infectious disease emergence and contagion are more dangerous than ever” due to overpopulation, urbanization, industrial livestock crowds and mobility.

The panel estimated that there was a 20 per cent chance that four pandemics could unsettle the globe over the next century.

The late Joshua Lederberg, a Nobel Prize winning biologist, warned more than a decade ago that the world had entered a disquieting era of plague making.

“We have crowded together a hotbed of opportunity for infectious agents to spread over a significant part of the population. Affluent and mobile people are ready and willing and able to carry affliction all over the world within 24 hours’ notice. This condensation, stratification and mobility is unique, defining us as a very different species from what we were 100 years ago,” he wrote.

As dramatic agents of biological change pandemics resemble tsunamis or bombs. They can wash over continents changing political arrangements, religious beliefs, artistic endeavours and economic habits.

Or they can blow up fossilized institutions and destabilize political dynasties.

In the past they have stopped wars and started them. Pandemics have the energy to rattle and even collapse civilizations. Think of them as mighty and uncertain biological recalibrations.

As COVID-19 provokes the usual spate of plague behaviours (fear, dread, generosity and compassion) it is worth remembering that pandemics remain critical and immutable social forces that shape our lives. They paralyze and disrupt. They reveal and renew. Here then are 10 characteristics that the global economy and its elites have mostly ignored about the energy of pandemics:

1. Pandemics are one of four biblical horsemen that give meaning to our lives and shape human history.

The White Horse represents the word of God or truth. The Red Horse symbolizes the power of the state over peace and war. The Black Horse, for good and ill, commands the busts and booms of economics and famines. Last but not least, comes the Fourth Horseman. It represents the disquieting influence of microbial life and pestilence. As I noted in my book The Fourth Horseman nearly 30 years ago, we don’t like to think that we are a part of history anymore, but we are walking memories of past plagues.

2. Pandemics may appear as random events, but are really the product of cultivated vulnerabilities by different civilizations at different times.

Homo sapiens have a long history of provoking plagues with overcrowding, dirty water, deforestation, poor nutrition, ruinous poverty, soil erosion and novel agricultural practices.

Influenza, for example, started to unsettle the globe when Chinese farmers added ducks to rice paddies to control insects in the 16th century. That single change put avian viruses in close proximity to pigs, which helped the virus jump to humans.

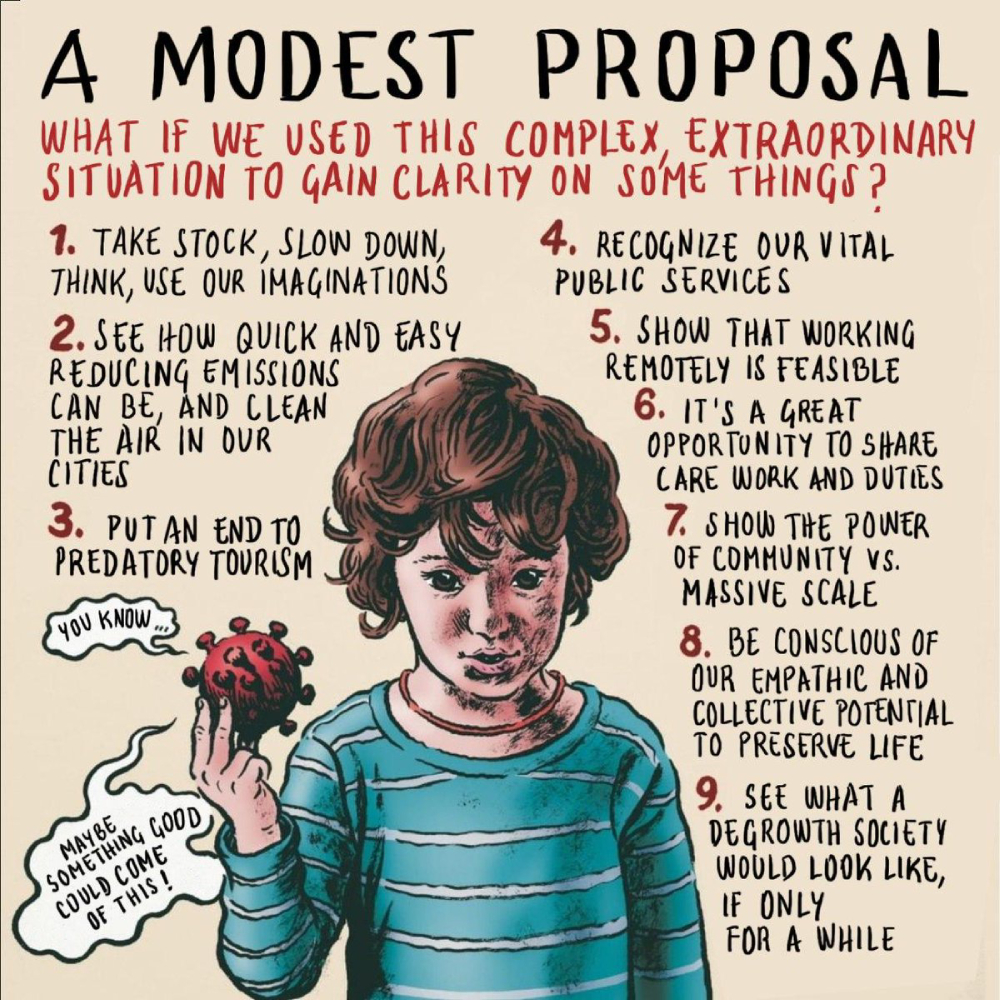

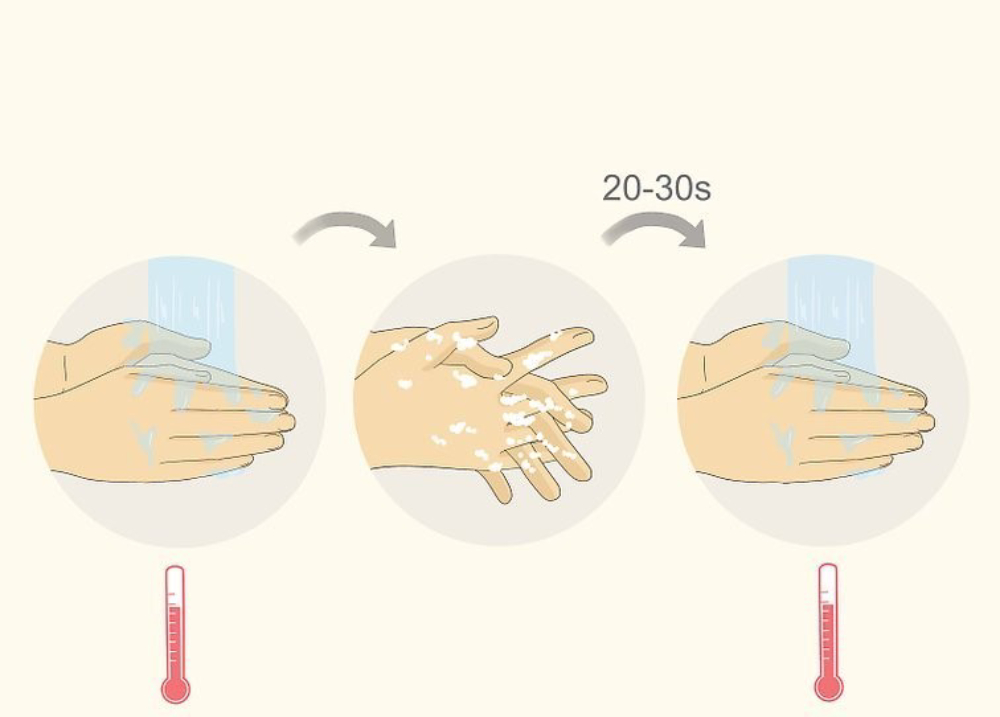

3. So-called “non-pharmaceutical interventions” such as hand washing, social isolation and the banning of crowds can dramatically slow the spread of a viral plague.

In contrast vaccines and drugs rarely arrive on the scene until the pandemic has waned. In fact material changes in human behaviour, housing, nutrition and hygiene have always had the most impact on slowing or stopping plagues.

The experiences of COVID-19 in South Korea and Italy illustrates how rapid changes in human behaviour can alter outcomes.

South Korea, a neighbour of China, tested early, traced down the infected, isolated them in their homes and generally restricted travel. Italy did not test or contain aggressively. While Korea tested 240,000 to find and isolate nearly 8,000 cases, Italy tested but 97,000 citizens and watched infections explode to nearly 20,000.

As of March 14 South Korea had 67 deaths. Meanwhile Italy has lost more than 1,266 citizens, a death rate of seven per cent for those known infected, much higher than South Korea’s.

4. Pandemics invite a rude parade of blame, conspiracies and religious zealotry.

As waves of plague undid Europe fearful authorities scapegoated Jews for spreading the Black Death. (They practiced better hygiene and therefore were suspect by the afflicted.) During the industrial revolution working people thought that the rich had invented cholera to murder the poor.

In scores of riots they attacked the rich, hospitals and doctors. When the Spanish flu pandemic hit Africa, white South Africans blamed blacks for the mounting death toll because blacks worked in the most crowded and appalling work places. That blame eventually morphed into a noxious political policy: apartheid.

COVID-19, of course, initially directed a surge of racism against Chinese citizens even though the virus probably did not originate in Wuhan’s wet market as widely reported. The market merely spread the virus.

5. Global trade has always played a formidable role in disease exchanges.

The Silk Road brought rats and fleas to 13th-century Europe resulting in a demographic collapse in which one in four people died. The slave trade bombarded two continents with epidemics. Waves of cholera epidemics followed European trade routes from the Ganges Delta to the slums of major cities. Global steamship traffic dutifully carried influenza around the world and played a key role in spreading the deadly Spanish flu pandemic.

6. Each and every pandemic leaves a unique and unpredictable legacy.

The Black Death killed so many people that feudal landlords were forced to increase wages and decrease rents to keep labour. The die-off also changed humankind’s relationship with God and nature.

In the 17th century syphilis changed sexual politics between men and women and public baths fell out of fashion. Tuberculosis epidemics illuminated the perils of homeless and forced migrations. And so on.

7. As great disturbances in human affairs, pandemics invariably unsettle and change economies.

Smallpox emptied the Americas and allowed Spain to loot the region of its gold and silver. Smallpox also played a major role in shaping the ebb and flow of Canada’s bloody fur trade by dramatically killing off entire First Nations on the plains.

The Spanish Flu of 1918 to 1919 killed at least 50 million people and erased five per cent of global gross domestic production. Ebola ate up 10 per cent of the GDP of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea in 2014 and 2015. COVID-19 likely will be the costliest pandemic due to the complexity and fragility of globalization.

Some pandemics undo economies with mass die-offs but in most modern cases it is the fear of infection that bleeds financial systems.

8. Pandemics rudely outline weaknesses and faults in political leadership. Good leaders lessen their impacts while incompetent leaders add to the gravity.

President Woodrow Wilson was so focused on the First World War that he ignored repeated warnings about influenza and its impact on Atlantic troop movements to the Western Front. At the end of the war Canadian and U.S. authorities knowingly put sick troops on cramped ships with poor ventilation. As a result the flu killed 675,000 Americans while the trench warfare claimed but 53,000 U.S. soldiers.

President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa didn’t think HIV was caused by a virus and thousands died.

President Donald Trump, who initially accused his political rivals of perpetrating a “hoax” when they warned his administration wasn’t doing enough about COVID-19, failed to prepare the United States with adequate testing and containment. Then, saying “I take no responsibility at all,” he falsely blamed the Obama administration for inadequate testing kits.

9. Pandemics are rarely equal opportunity events.

They might scare everyone but they don’t kill everyone: They tend to target the poor, the vulnerable and those wounded by bad health.

The Black Death struck down both rich and poor but really focused on the malnourished and the frail.

Smallpox became a terror for Indigenous Peoples because they had no immunity to this novel Old World virus. During the Spanish flu members of First Nations died at rates seven times higher than British Columbia’s provincial average.

Cholera primarily dogged the working class. HIV initially targeted marginalized communities: gay men and drug users. Ebola affected the poorest of the poor. To date COVID-19 seems to affect the elderly and unwell disproportionately.

10. Ultimately, pandemics invite us to question disturbances in the human family.

COVID-19, for example, could provoke challenges to the unsustainable complexity of technological life as well as the deadly biological traffic in all living organisms on a planet now crowded by eight billion people. We might, after the storm has passed, question the vulnerability of monocultures and the globalization of everything.

Long after the monotony of deprivation and separation, the survivors of pandemics will kiss and hold their loved ones with a new appreciation. They might light candles, true plague light, and offer prayers of thanksgiving.

The humbled will be thankful, as author of The Plague Albert Camus once was, for what pandemics have always taught those receptive to biological instruction: “There are more things to admire in men than to despise.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: