Are British Columbians crazy?

According to one popular definition, a lunatic is someone who performs the same action, over and over again, yet each time expects a different result. By that explanation, and in the context of our province's balanced-budget legislation, B.C. residents -- all 4.3 million of us -- must be crazy, indeed.

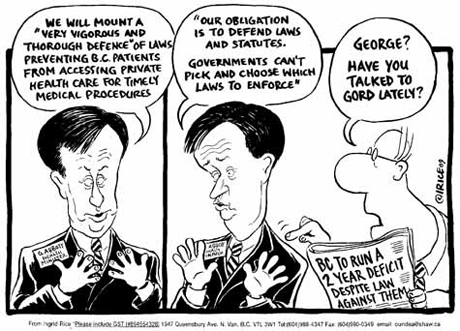

Premier Gordon Campbell and Finance Minister Colin Hansen have announced that B.C. will incur fiscal deficits in each of the next couple of years.

Of course, B.C. has a balanced-budget statute that specifically prohibits the government from planning a shortfall at the beginning of any fiscal year, and punishes cabinet ministers should a deficit appear at the end of the period.

To get around the law, Campbell also admitted that the legislature would be recalled in a little over a week so his government can repeal (or fundamentally amend) the balanced-budget legislation his own administration enacted not quite eight years ago.

A decade before that, in 1991, B.C. became the first province in Canada to pass balanced-budget legislation. In fact, we seem to like them so much that over the last two decades we've also passed more of them -- three -- than any other province.

Still, because provincial budgeting often has proved to be a difficult task, our politicians have quickly discarded each balanced-budget statute when faced with economic challenges. So, British Columbia also has repealed more balanced-budget laws than any other jurisdiction in Canada.

Three balanced-budget laws up, and three budget-balanced laws down.

If doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting a different result each time, qualifies as crazy, well, maybe its time to put padded walls around the legislature.

The first go at it

Social Credit Finance Minister Mel Couvelier took the initial step towards balanced-budget legislation in B.C. 18 years ago. "In planning our operating budgets, we intend to incorporate a longer-term framework," Couvelier told the legislature on April 19, 1990, during his budget speech.

It fell to Couvelier's successor, John Jansen, to introduce B.C.'s first balanced-budget law with the 1991/92 budget. "Families have to balance their budgets and carefully plan their financial futures," Jansen said. "Government's must do the same."

The Taxpayer Protection Act not only was the first in B.C. to require a balance between revenues and expenditures, but also the first in Canada.

Sadly for Social Credit, Jansen's budget was the last the once-mighty political party ever would introduce in the legislature because in October 1991, the Socreds were turfed from government by Mike Harcourt's New Democratic Party.

Still, Social Credit's balanced-budget legislation appeared safe because after it was introduced by Jansen, every single NDP MLA present in the legislature voted in favour of the bill.

Moreover, during the 1991 election campaign, NDP leader Harcourt had unveiled his very own "Fiscal Framework," which showed B.C. voters how a New Democratic Party government would balance revenues and expenditures over a five-year economic cycle.

Call it a 'tax freeze'

In the spring of 1992, mere months after winning election to government with a commitment to balanced budgets, the Harcourt New Democrats repealed the Taxpayer Protection Act.

"This act was passed only last year," Finance Minister Glen Clark told the legislature on April 8, 1992. "It was apparently an attempt by the previous government to stop tax increases by legislation." Clark, who a year earlier had voted in favour of the Taxpayer Protection Act, now belatedly seemed to confess that he hadn't understood what he voted for.

He added: "The government has concluded, after review of the province's financial position, that continuing the tax freeze would be unrealistic and financially irresponsible."

Instead, Clark said, the Harcourt government opted "to produce a balanced package of controlled spending growth, greater efficiency and revenue increases."

Those "revenue increases," were undertaken immediately, as Clark boosted taxes by about $800 million annually in his first budget, and then by another $800 million in his second.

Still, despite these enormous tax lifts, government spending continued to climb ahead of revenues, and the result was an on-going succession of budgetary deficits.

Suicide by deficit

Finally, in 1995, bare months before an expected general election, Clark's successor as finance minister, Elizabeth Cull, unveiled a budget with a razor-thin surplus. While a far cry from the NDP's 1991 promise of balanced revenues and expenditures over a five-year economic cycle, a single balanced budget at least pointed in the right direction.

But instead of going to the polls in the fall of 1995, Harcourt quit politics over a party scandal, and the New Democrats were forced to hold a leadership convention. Clark won that contest -- and thereby became premier -- as B.C.'s economy, among the best in Canada during the early years of the decade, faltered.

It would have been suicidal, politically-speaking, for the NDP to unveil a pre-election deficit in 1996 after having introduced a balanced fiscal plan in 1995. And so, Cull brought in a second consecutive balanced-budget, which, like her first, also boasted an exceedingly slim surplus. One month later, Clark's New Democrats scored a surprising re-election victory.

Within weeks, new NDP Finance Minister Andrew Petter (Cull had lost her seat in the election) confessed that both pre-election fiscal plans, for 1995/96 and 1996/97, would end with deficits. A new phrase soon entered the province's political lexicon -- Fudge-it Budgets.

'This bill has teeth'

Four years later, after the Fudge-it Budgets had spawned a lengthy investigation by the auditor general, the B.C. Supreme Court had rejected a suit alleging election fraud, and a couple of government-appointed advisory panels prepared lengthy proposals for reform, the New Democrats brought in their own balanced-budget law.

"This bill has teeth," NDP Finance Minister Paul Ramsey insisted. "There are consequences for failure to meet the targets set out in this bill." Those targets included a steady reduction in B.C.'s annual deficit until 2004, at which time it was to be completely erased. The teeth came as a promise to levy a 20 per cent pay cut on cabinet ministers should a deficit appear on the province's books.

Notably, the NDP balanced-budget law had a couple of significant exemptions. As Ramsey described it, the government's obligation to avoid deficits would be abandoned in "an emergency of unexpected circumstances that imperils health or safety of British Columbians, or if revenue is declined by more than $500 million year over year."

Gary Farrell-Collins, the BC Liberal finance critic, responded by insisting that his party, too, endorsed a balanced-budget law. "This side of the house has always supported balanced-budget legislation," he said. "We continue to support balanced-budget legislation."

Still, when the NDP's balanced-budget bill went to second and third reading, the entire BC Liberal caucus -- Gordon Campbell among them -- voted against the measure.

BC Libs take a whack at it

To the surprise of nearly every British Columbian, the provincial deficit was eliminated well before Ramsey's 2004 target. Thanks to a sharp spike in revenues (primarily from personal income taxes and energy exports), B.C. recorded a tiny surfeit in 1999/2000, and then a gargantuan $1.4 billion surplus in 2000/01.

The latter arrived too late to save the New Democrats, however, and in May 2001 Campbell's BC Liberals won a massive electoral majority. One of the new government's first priorities, of course, was to repeal the NDP balanced-budget law and introduce one of their own.

But despite inheriting the biggest surplus in provincial history, the Campbell government's balanced-budget law would not require a surplus until 2004!

Why the delay? For reasons that forever will defy rational explanation, Campbell and Collins decided to slash the province's revenues by about $2 billion (through tax cuts), while at the same time boosting government expenditures by a comparable $2 billion.

The result was to transform Victoria's books, seemingly overnight, from the biggest surplus in history (in 2000/01) to a series of the largest deficits ever seen in the province -- $1.3 billion in 2001/02, $3.2 billion in 2002/03, and $1.3 billion in 2003/04.

By then, the global commodity boom was well underway. Federal transfers to B.C. (and all provinces) skyrocketed, corporate income taxes soared, and natural resources revenues (especially from natural gas) headed for the stratosphere. Consequently, over a four year period, from 2004/05 until 2007/08, B.C. enjoyed some of the largest surpluses in provincial history.

Throwing in the towel

Today, the commodity boom seems to have ended, the global economy is in the early stages of a severe downturn, and across the world, governmental revenues have plummeted.

After a handful of budgetary surpluses, Gordon Campbell has thrown in the towel: B.C.'s third balanced-budget law will be gutted, and the BC Liberals will return to the massive deficits that marked their early years in office.

What, then? Should British Columbians expect a fourth balanced-budget statute in the not-too-distant future? Then, later, maybe a fifth and a sixth? More to the point, what value has a balanced-budget statute when governments can repeal, amend or gut it whenever economic and fiscal challenges prove difficult?

Simply, we must be crazy to keep enacting balanced-budget laws when the utility of such legislation is non-existent. Or, at least crazy enough to keep electing politicians who claim that balanced-budget legislation will ensure their government's fiscal responsibility.

We all should remember the words of Gordon Campbell, then leader of the Opposition, when he voted in 2000 against the NDP's balanced-budget legislation: "It's amazing how rewriting laws can work for a government that doesn't really care about the law."

Related Tyee stories:

- Deficit budgets planned for BC

- Ready for a Slump?

As BC's economy cools, how well are we prepared? - Campbell Misled Public on NDP Finances

In 2001 the incoming premier called NDP finances "worse than we anticipated." His briefing binders, gained by The Tyee through an FOI, told him the opposite.

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: