British Columbia's legislative assembly has been recalled to enact financial legislation Premier Gordon Campbell says is intended to help B.C. avoid recreating the "worst crisis in over 75 years," the Great Depression that lasted from 1929 to 1933.

Such comparisons between the present and not-too-distant past have become ubiquitous in recent days. Last week, for example, Paul Krugman, the New York Times columnist and winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize for economics, penned a column under the headline "Franklin Delano Obama?" in which he asked rhetorically, "how much guidance does the Roosevelt era really offer for today's world?" (The answer: "a lot.")

And Time magazine carried the Obama-Roosevelt comparison even further, with a cover caricature showing the newly-elected U.S. president as FDR at the wheel of his Packard Twelve automobile. The 2008 presidential election, Time observed, "has been compared to Franklin Roosevelt's ouster of Herbert Hoover, another transition that occurred amid economic carnage."

Is the present day really reminiscent of the Roosevelt era? Are we, to use Time's words, today witnessing "economic carnage" not dissimilar to that of the Great Depression?

More to the point, what really happened to British Columbia and the province's finances 75 years ago?

The following is a look at B.C.'s fiscal situation in the Great Depression.

'The Millionaires' Government'

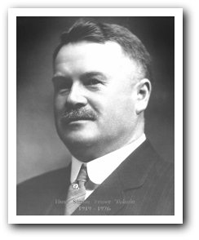

William Curtis Shelly, B.C.'s new Conservative finance minister, rose in the legislature to give his first-ever budget address. The date was Feb. 21, 1929. Eight months earlier, after a dozen years on the opposition benches, the Tories finally had won election to government.

The newly-elected premier, Simon Fraser Tolmie, was a Saanich farmer and veterinarian who was elected Victoria's Member of Parliament in 1917 and served in the federal cabinet as minister of agriculture. In 1926, against his wishes, the fractious provincial Tories chose him to be their leader.

Unlike many of those in his government, Tolmie was a man of relatively modest means. Indeed, such was the conspicuous wealth in the Tory caucus that some wags dubbed it "the Millionaires' Government." And William C. Shelly, the new finance minister, was one of the wealthiest of them all.

A baker's son, the Ontario-born Shelly moved to British Columbia in 1910 to join his brother, also a baker. Together, the two became renowned in Vancouver for their Four-X bread, delivered door-to-door in neighbourhoods across B.C.'s Lower Mainland in gleaming vans drawn by prize-winning horses. That popularity led Shelly into politics, and in the aftermath of the First World War he served as chair of the Vancouver parks board and was an alderman on city council.

But William C. Shelly was more than just a successful baker and politician; he also was an extremely astute businessman. Indeed, in the mid-1920s he helped assemble a business conglomerate called Canadian Bakeries Ltd., into which he sold his company for $1.1 million -- an astounding sum, considering that the average British Columbian then had a yearly income of about $500. Shelly thereafter worked as Canadian Bakeries' vice-president and general manager.

His business interests extended well beyond the baking and selling of bread, however. In the 1929 Canadian parliamentary guide, Shelly's biographical sketch requires a whopping 24 lines, which show that on top of his Canadian Bakeries' duties, he was president of six other companies -- Home Oil Co. Ltd., Canada Grain Export Co. Ltd., Guaranty Savings and Loan, Crescent Beach Development Co. Ltd., Grouse Mountain Highway and Scenic Resort Ltd., and the Shelly Building -- and a director in several more.

Of all the members of his Conservative caucus, it seemed that Tolmie could hardly have found anyone better-suited to head the finance department than William C. Shelly.

A finance minister's fortune

The period when Shelly amassed his considerable fortune, between the end of the First World War and the beginning of the Great Depression, was a time -- like so many others in B.C. history, before and since -- of great economic growth.

From 1918 to 1929, the provincial population soared from 474,000 to 659,000 -- an increase of 39 per cent -- and Vancouver overtook Winnipeg to become, after Montreal and Toronto, Canada's third-largest city.

With the opening of the Panama Canal, B.C. forest products found markets on the U.S. east coast and in Europe, and the volume of timber cut in the province leaped from a total of 4.8 million board feet between 1901 and 1910, to more than 24 million in the 1920s.

The growing popularity of the automobile and expansion of electrical generation also stimulated the development of B.C.'s mineral assets, notably lead and zinc. Production of the former jumped by a factor of eight over the course of the decade, from 40 million pounds to 320 million, and growth of the latter was similar.

The Panama Canal also sparked the growth of B.C. as an export centre for prairie wheat. In 1921, Vancouver had the only grain elevator in the province; by 1929 the city had six, and New Westminster and Victoria one apiece. B.C.'s grain exports, which stood at 68,000 bushels annually at war's end, exceeded 99 million bushels in 1928/29.

Over the same period, exports of all products -- lumber, wheat, metals, minerals and so on -- jumped from 1.5 million cargo tons, to 6.3 million.

Era of growth and spending

The provincial government's yearly revenues showed a similar upward trend. In 1916/17, when the Liberals took power, receipts totaled $6.9 million. When they left office in 1928/29, that figure had tripled to $21.2 million.

But expenditures also grew at a comparable pace, rising from $9.5 million to $21.9 million over the period. In the dozen years the Liberals were in office, just three ended with very small surpluses, and the remainder had shortfalls as high as $3.2 million.

As a consequence, the province's net debt also grew substantially. Pegged at $8.4 million on the eve of the Great War, it had climbed to $61.5 million at the start of the 1920s (in part because Victoria was forced to take over the failing Pacific Great Eastern Railway), and stood at $89.4 million when Shelly introduced his first budget.

The interest on the debt in 1929/30 was $7.3 million -- or about one-quarter of all government expenditures in the fiscal year.

As Shelly dryly noted in his first budget, "the trend of the financial obligations of this Province are somewhat alarming."

Charges of bad business

Like many other finance ministers in B.C. history, Shelly used his inaugural budget speech to excoriate his political opponents in the defeated Liberal administration.

One of the most serious examples of Grit financial mismanagement he cited was "inexcusable procrastination" regarding the sale of provincial debentures in 1928. Reading excerpts from letters and telegrams sent between government officials in Victoria and financiers in New York, London and eastern Canada, Shelly told the legislature how the Liberals had failed to heed advice to go to the market (to borrow capital) when demand for government bonds was strong and yields (interest rates) relatively low.

By the time the Conservatives took power, the global securities market had weakened and a bond issue similar to that which should have been floated earlier was forced to offer a higher yield to attract buyers. The Grits, Shelly charged, with their "unjustifiable apathy and procrastination," had cost British Columbians nearly $2.6 million in additional interest costs (compounded over a 25-year period).

He also blamed the Liberals for overstating the value of provincial assets, understating capital expenditures, and misspending trust funds. Most concerning was a questionable accounting change whereby Victoria's debt repayment outlays were separated from the annual budget's operating expenditures.

"I can say without fear of contradiction," Shelly thundered, "that any business organization would be subject to the most severe criticism if such methods of presenting accounts and estimates were adopted...."

Echoes of Herbert Hoover

Throughout the budget speech, Shelly called for "business principles" to be adopted by the government. And he concluded his address with the observation that "it is in my considered opinion the whole country is yearning for less political strife and more business methods applied to governmental operations."

Such a view was not then unique to Shelly nor to British Columbia. Twelve days later, a newly-elected U.S. president with a similar philosophy was sworn into office.

"The election has again confirmed the determination of the American people," said Herbert Hoover on March 4, 1929 in his inaugural address, "that regulation of private enterprise and not government ownership or operation is the course rightly to be pursued...."

Andrew Mellon, Hoover's treasury secretary -- a Pittsburgh banker and one of the richest men in the United States -- later put it even more succinctly: "The government is just a business, and can and should be run on business principles."

'Stiffer and stiffer' credit markets

With the benefit of hindsight, the most interesting of Shelly's budget remarks are those regarding the deteriorating market for securities in New York, London and elsewhere. "It is a curious cycle we are in," he said, quoting from one financier's letter, "and it may last for some time." Another missive, also from back East, observed that the market was "extremely flat and there is very little demand."

Shelly himself noted that "the money market [in 1928] had taken the most peculiar cycle it had for years," and further added, "the markets were becoming stiffer and stiffer." Such comments proved eerily prescient; the bond markets, we know now, were providing an early signal of impending economic weakness.

In September, about six months after Shelly's first budget and Hoover's inauguration as U.S. president, stock markets in New York, Toronto and elsewhere across North America were hit by a wave of selling. This early sell-off was quickly followed by a short-term recovery, but then the pattern repeated itself, again and again.

On Oct. 24 came Black Thursday, "the most devastating day in the history of the markets." according to economist John Kenneth Galbraith (in his book, The Great Crash).

Stocks fell in a death spiral that continued through the rest of the year. A brief recovery occurred in early 1930, but the downward trend resumed again in the summer and did not halt until the bottom was hit in June 1932.

After the crash

The stock market crash of October 1929 did not cause the global economic depression that gripped the industrialized world in the 1930s. But it was a defining event that signaled a dramatic end to a hitherto unprecedented era of rising prosperity and progress, and the beginning of a lengthy period of economic uncertainty, social turmoil and political upheaval.

The last years of the Roaring '20s marked an economic peak that would not soon be seen again. In B.C. in 1929, the average annual income hit $600; four years later it had dropped all the way down to $353.

Similarly, the gross value of manufactured products in B.C. in the year of the crash was $273.7 million; four years later it was about half that figure, $140.5 million. And whereas the value of construction contracts in the province in 1929 totaled $54.4 million; the comparable figure in 1932 was one-sixth as much, a mere $8.6 million.

Thousands upon thousands of people lost their jobs. Among trade union members in B.C., the unemployment rate skyrocketed from a minuscule 2.6 per cent in June 1929, to a nearly-unbelievable 26 per cent in December 1932.

Already shaky, the provincial government's finances underwent a dramatic deterioration. Revenues collapsed, the fiscal deficits grew even larger, and the debt soared ever higher.

And in a shocking development, William C. Shelly, the province's business-oriented finance minister and one of B.C.'s wealthiest individuals, lost nearly everything he owned.

On Friday, part 2: A rich and optimistic finance minister rings up the biggest shortfall in B.C. history.

Related Tyee stories:

- The Meltdown, Seen from Below

What union leaders, labour experts and anti-poverty activists say needs to be done. - Surplus shrinking, but no major cuts planned: Hansen

- A Prairie Marxist's Memoir

From young communist to senior citizen fighting for health rights. At 95, Ben Swankey tells his story.

Read more: Politics, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: