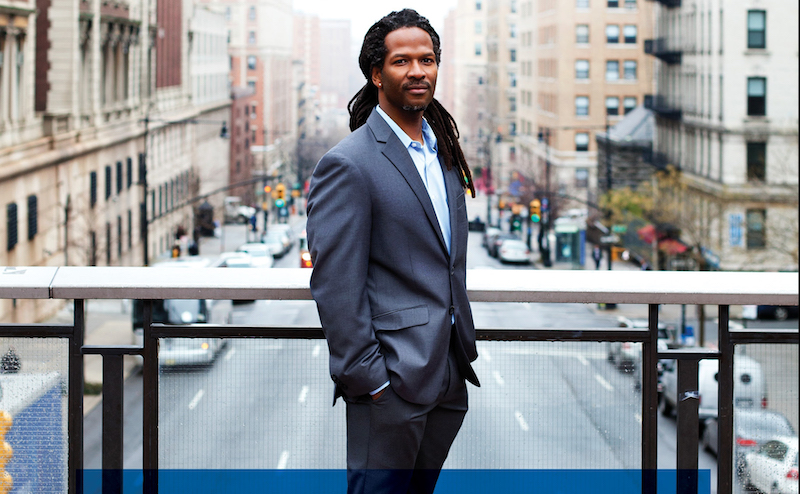

Nearly 30 years ago, Columbia University neuropsychopharmacologist Dr. Carl Hart set out to find the mechanisms in the brain responsible for cocaine addiction.

He couldn’t.

“After 20 years of being unsuccessful,” he explains, “I realized that the psychosocial environment — including laws — is far more important than the drugs themselves. And far more important than neurobiology.”

Like many of his contemporaries, Hart had subscribed to the narrative that addiction is primarily a disease of the brain — one with neurobiological causes, requiring neurobiological solutions.

But this new realization changed the course of his work, and today, in addition to being the chair of Columbia’s psychology department (and Columbia’s first tenured African American professor of sciences), Hart has written extensively on the topic of drug use.

His thoughts on the current opioid crisis have appeared in the pages of Scientific American, Nature and the New York Times. His book, High Price, a memoir that deconstructs our current notions about drugs and society, won a PEN/Faulkner Award for non-fiction.

He also does public speaking engagements where he argues in favour of a radically different approach to drug policy, one informed by empirical evidence, as opposed to the current model, which, he argues, is largely based on a misconception.

Hart will give such a lecture at the Peter Wall Institute’s upcoming Wall Exchange on May 23 at the Vogue Theatre in Downtown Vancouver.

“This is really about adults having the right to choose their pleasures,” he says. “And the people who are addicted to drugs — they’re not addicted to the drug because it’s a drug. It’s because of psychosocial factors. The vast majority of people who use any drug never become addicted. So, we can’t blame the drugs.”

Most drug users, Hart says, are just regular citizens who raise families and pay their taxes. The exception to that rule, he points out, is areas like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside where addiction is common and the presence of fentanyl in the drug supply has led to an increase in overdoses.

However, he argues that even in those cases, characterizing addiction as a mental illness is still a mistake.

“Thinking about the Downtown Eastside, the majority of people who are using these drugs are addicted,” he says. “And that keeps us from looking at the fact that many of those people are mentally ill. Many of those people are impoverished. Many of those people have a lot of psychosocial issues. But we’re looking at it and fooling ourselves by saying: ‘Well, that’s just drug use.’ And we’re not helping anyone by doing that.”

According to Hart, western drug policy has long been used as a tool to control already marginalized populations, and rather than being informed by science, it has roots in decades of racial prejudice.

“Our drug laws have always been particularly restrictive, and tightly connected to an outgroup — people who were feared or despised,” he notes. “That’s always been the major motivating factor when it comes to drug laws.”

As an example, Hart cites the U.S.’s first anti-drug laws, passed in 1914 to regulate opioids and cocaine. They were passed in response to drug prohibition laws first enacted in Canada in 1908, which were based entirely on unfounded fears about Chinese Canadians.

“Those laws were passed because of fear of the Chinese, particularly in places like San Francisco,” he says, of America’s 1914 laws. “It was about protecting good, white folks from the opium dens. And as far as cocaine — in the South, they were afraid of black cocaine users. So they vilified both of these drugs, and married drug use to those particular groups. And that facilitated the passage of these laws.”

A 2018 report to the UN drafted by the International Drug Policy Consortium derided the global war on drugs as a failure, responsible for spiking murder rates and mass incarceration, while having no overall effect on supply or usage. The brief, presented by a network of more than 170 NGOs, urged a shift in thinking, particularly in the United States. Canada received praise for its more effective response to the overdose crisis, but as Hart explains, it’s not enough.

“If we provide people with a better education about drugs, that would help,” he notes. “And we can make sure that people have access to drug checking — not just fentanyl test strips, real drug checking, where they do a complete chemical readout of what’s in a substance — then they’ll know what kind of fentanyl they’re dealing with, because some types are more dangerous. We can also just provide heroin to folks who need heroin.”

Where Hart’s views might have been considered a fringe perspective even a few years ago, they’ve since become part of a broader, international conversation about drug policy, one focused on harm reduction and empirical evidence. In the Downtown Eastside itself, Providence Health’s Crosstown Clinic has been administering legal, medical grade heroin to more than 300 chronic users since 2014.

Clinics in Switzerland, where Hart has spent time, offer the same service. Portugal decriminalized drugs almost 20 years ago, and the effect on crime and addiction statistics has been startling.

“At Columbia, we have been giving these drugs — heroin, cocaine, crack, marijuana, methamphetamine — to people for decades, and I personally have given thousands of doses of drugs to these people without incident,” says Hart. “So that tells you that these things aren’t a big deal once you have the education on dosing, and that sort of thing. This is already happening.”

His dream, moving forward, would be the widespread adoption of legislation like Portugal’s — decriminalization and regulation of all substances, from heroin and cocaine to LSD and ketamine. But while he continues to advocate for common-sense, evidence-based drug reform, Hart’s vision of the future isn’t particularly sunny.

“Ideally, we would have a wide range of psychoactive substances available for purchase,” he says. “So that adults could buy them from stores that are regulated. Where there’s quality control. I don’t know if that will happen in the United States in my lifetime, so I’m making plans to move somewhere that has at least decriminalized drugs. I have no interest in staying in a country where I can’t get the psychoactive substances I like to have. I’m a neuropsychopharmacologist. I’ve given out thousands of doses. I’ve been studying this for 30 years. Why should some idiot tell me what I can and can’t have? They don’t know better than me.”

Join the Peter Wall Institute on May 23 at the Vogue Theatre for the Wall Exchange featuring Carl Hart. This event will also feature a response with local perspective from Caitlin Shane (Pivot Legal Society) and a Q&A session moderated by Garth Mullins (Crackdown podcast). Get your FREE tickets here. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Politics

This article is part of a Tyee Presents initiative. Tyee Presents is the special sponsored content section within The Tyee where we highlight contests, events and other initiatives that are either put on by us or by our select partners. The Tyee does not and cannot vouch for or endorse products advertised on The Tyee. We choose our partners carefully and consciously, to fit with The Tyee’s reputation as B.C.’s Home for News, Culture and Solutions. Learn more about Tyee Presents here.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: