- The New NDP: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing

- UBC Press (2019)

On election night Nov. 27, 2000, David McGrane reminds us, the New Democratic Party of Canada hit bottom. It had gained only 8.5 per cent of the vote and just 13 seats, down from 21 seats in the 1997 election.

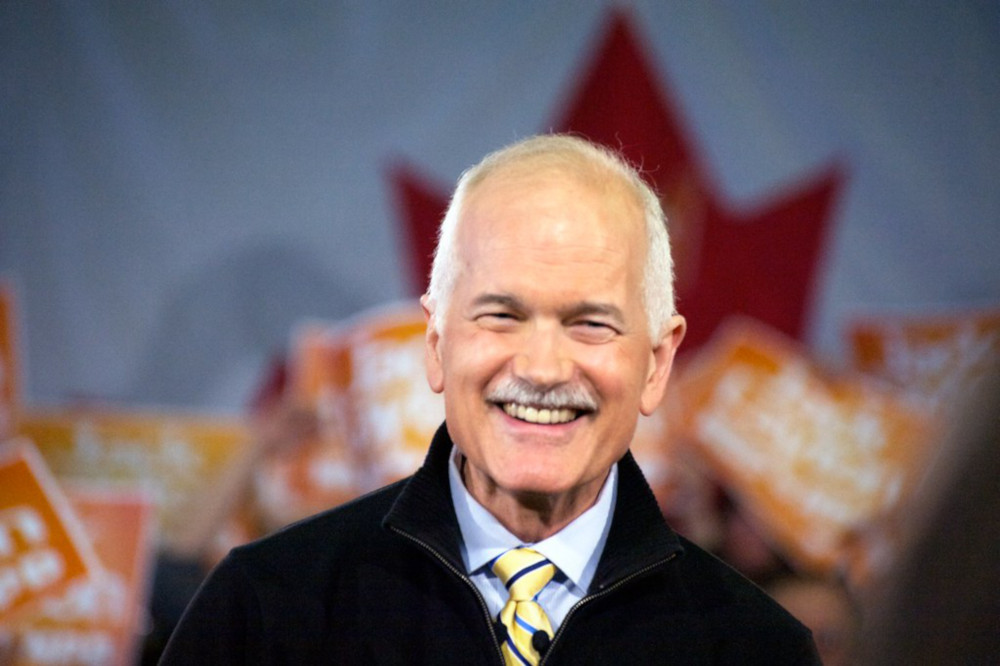

McGrane, himself an NDP insider, describes the party’s slow but steady climb back under Jack Layton and Tom Mulcair until, after 2011, it was the Official Opposition and a government in waiting. Then in 2015, everything fell apart.

The book is like a forensic accountant’s analysis of a startup’s path from concept to riches to bankruptcy. McGrane interviewed scores of New Democrat MPs and staffers and dug into the voting patterns of key elections — especially 2015. Bob Rae, himself once a New Democrat, has called the NDP more of a movement than a political party; McGrane describes how the movement did indeed become a party.

To do so, McGrane says, the NDP moderated and modernized; it did so by changes in political funding that let it hire professional operatives working for the leader. The professionals used “postmodern campaigning” to steal voters from the Liberals and the Bloc Quebecois. That is, the party turned to multimedia, email, “microtargeting” specific groups, and a permanent campaign for a “presidentialized” leader who became the party’s brand.

That involved a considerable culture change. The NDP had always paid more attention to its members than to the non-members whose votes it needed. After 2000, members were increasingly seen as donors and local foot soldiers, while the professionals ran focus groups to see what the rest of the electorate wanted. The pros then built platforms to appeal to non-NDPers while ignoring members’ tedious policy resolutions at party conventions.

No more ‘freelancers’

The pros also taught discipline to NDP MPs. In the 1980s and 90s, “freelancer” MPs had publicly disagreed with their leader or with particular party policy. Svend Robinson was a famous freelancer, and now that he’s back running for the party in Burnaby North-Seymour, he’s already out of step with his leader, Burnaby South MP Jagmeet Singh.

Freelancing in other parties is better known as “bozo eruptions,” when ideological warriors embarrass their parties by saying what they believe. But for a decade and a half, increasingly centralized control by the leader has suppressed such eruptions in all parties. Good marketing demands a clear party line.

For the NDP and Stephen Harper’s rebranded Conservatives, such marketing paid off. The Liberals freelanced themselves into third place and imminent oblivion, until Justin Trudeau’s famous boxing match. Meanwhile, Jack Layton was like Steve Jobs brought back to Apple — the leader who turned a failing brand into a powerhouse, and then died.

Strikingly, McGrane spends almost no time discussing personalities, whether of the party’s leaders or anyone else. The postmodern leader is a brand, not a person with a vision and the skills to realize it. Reviving a political party happens in the back rooms, not out on stage where the charming leader passes out great sound bites to the media and poses for selfies. The faceless professionals who ran focus groups, commissioned polls, and drafted platforms were the real saviours of the NDP — and, for that matter, Harper’s Conservatives and Justin Trudeau’s Liberals.

Moderation, modernization, and marketing

The membership might grumble about how the party was selling out, but its moderation, modernization, and marketing delivered ridings never dreamed of before. The 2008 election brought it eight new seats, for a total of 37; in 2011, Jack Layton finished off Liberal Michael Ignatieff in the leaders’ debate and saw the NDP become the Official Opposition with 103 seats, including 59 of Quebec’s 73 seats.

Given that kind of success, NDP members and MPs alike weren’t about to argue about strong control from the leader’s office. Layton presided over an institutional change that carried on after his untimely 2011 death. In 2012, Tom Mulcair became the highly presidentialized leader of a government in waiting.

Until he wasn’t anything of the sort. McGrane’s forensic examination of the NDP’s 2015 election collapse is almost painfully detailed. In oversimplified summary, the newly professional NDP had stolen a lot of Liberal and Bloc Quebecois votes in 2011. In 2015, the Liberals, BQ, and Conservatives stole them back.

Worse yet, a lot of those new 2011 voters, and some hardcore New Democrats, voted strategically in 2015 for whomever they thought had the best chance to oust Harper.

Worst of all, the professional NDP ran a terrible, awful, no good, very bad, very cautious campaign. When Harper called the election, Mulcair gave a dull statement and then refused to take media questions, squandering a golden chance to frame the campaign issues.

It was an unusually long campaign, and Trudeau’s Liberals had plenty of time to define themselves as the underdog champions of “#realchange.” The NDP, still wrestling with its perceived image as barking-mad Bolsheviks, let itself be outflanked on the left by Trudeau’s readiness to run a deficit. Fifteen years of focus groups and organization building led straight back to third-party status.

Soldier on, or take a Leap?

McGrane argues that the party has since faced two options: soldier on with professional post-modern party-building, or ditch it by going for a real re-framing of Canadian politics along the lines of the Leap manifesto the party had rejected years before.

Leap certainly seems to have been only a little ahead of its time. Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager who fills cities around the world with ever more climate protesters every Friday, would consider Leap a step or two in the right direction. The truly new Democrats in the U.S. Congress like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have made a Green New Deal a likely core issue of the 2020 presidential campaign.

So if Jagmeet Singh offered a Canadian Green New Deal, he might just catch the wave that Tom Mulcair missed in 2015.

McGrane offers no advice on such choices, but he does present seven “lessons” that the NDP and other social democratic parties might learn from 2015, including that “strategic voting is real” under our current first-past-the-post system. You’ll have to read the book to learn the others.

Jagmeet Singh would be wise to read it, too. “Love and courage” is a good slogan but a poor agenda. Perhaps he will hold onto enough seats to control the balance of power, as David Lewis did when Pierre Trudeau lost his majority in 1972.

Then again, he may take the party back to 2000, resign, and let someone else try to rebuild it — or turn it into a post-postmodern party with a fighting chance to get us through a disastrous century.

The Tyee’s federal election coverage is made possible by readers who pitched in to our election reporting fund. Read more about how The Tyee developed our reader-powered election reporting plan and see all of our stories here. ![]()

Read more: Election 2019, Federal Politics, Elections

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: