The NDP government, with a little help from the Greens, mostly got it right with changes to the two most important laws affecting the working lives of British Columbians.

But they still fall far short of the changes needed to reverse a long, destructive decline in the quality of jobs in B.C. and across Canada.

Long overdue partly because the former BC Liberal government ignored its responsibility to working people. In their first term the Liberals weakened the labour code, reduced the rights of workers under the Employment Standards Act, and gutted public sector union agreements.

For the rest of their 16-year stay in government the Liberals ignored issues affecting the working life of citizens. Any government that fails to increase the minimum wage for a decade crosses over from indifference to contempt for workers.

But the Liberals weren’t alone. Governments across Canada have failed to react as more and more of us are forced into precarious jobs without things considered the norm 50 years ago — basic benefits, pensions, stability, employment rights protected by a contract or the Employment Standards Act.

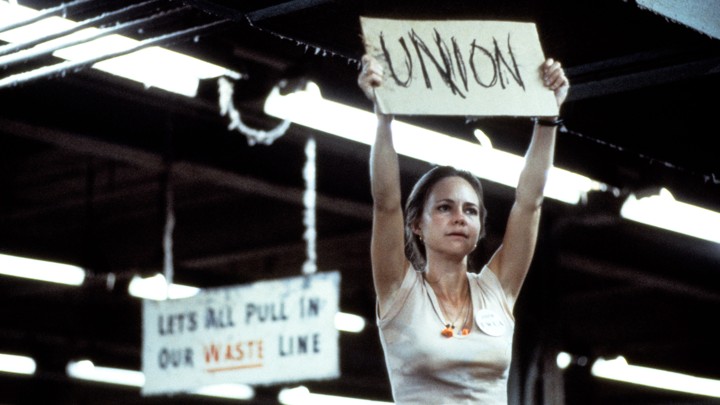

Recent changes to B.C.’s labour code, which covers anything to do with unions, should help, at least a little, in addressing that.

The research is clear. Unions bring higher wages, improved working conditions and greater job security for members.

But they also benefit workers in non-union organizations. A cursory look at the advice for companies seeking to avoid unionization shows that even the risk of unionization results in improved pay and benefits and better working conditions in non-union businesses.

But the rate of unionization has been falling in Canada since 1984. In B.C. private sector unionization fell by almost half in 10 years, from 24 per cent in 1997 to 16.7 per cent in 2016.

Partly that reflects a changing economy — the emergence of a hard-to-organize service economy, contracting, part-time work and the decline of forestry and the manufacturing sector. (Though a government concerned about its citizens would have changed the Employment Standards Act and labour code to reflect the changing world of work.)

But it’s also a result of Liberal government changes to the labour code that made it harder for employees to organize and bargain collectively.

The biggest change by the Liberals was to restore a requirement for an employee vote on unionization — it had been sufficient to get signatures from 55 per cent of workers in the proposed bargaining unit.

The result was a dramatic drop in new union certifications. From 1996 to 2000, about 380 new union certifications were approved each year. From 2006 to 2008, after the Liberals’ changes, that fell to about 100. Last year it was 58.

The requirement for a supervised vote is defensible. But the law also allowed a 10-working-day delay between the certification application and the vote. And unions maintain some employers use that time to pressure employees to change their votes, sometimes through threats, intimidation or firings.

(Since 2010, 10 employers have acted so badly that the board has ordered automatic certification of the bargaining unit. Between 1990 and 2007, 197 complaints of unfair practices by employers were filed with the Labour Relations Board and more than 75 per cent of them upheld, according to the independent three-person that reviewed the code.)

Labour Minister Harry Bains said he would have liked to eliminate the requirement for a vote. But the Greens opposed the measure, he said, and their three votes were required to pass it given Liberal opposition. (Which might have been a favour for the NDP government. The review panel recommended against eliminating the requirement and the Liberals would use it as a campaign issue.)

But the new labour code changes do cut the time between the certification application and the vote to five days from 10, leaving employers less time to interfere. The rules around employer communication — again changed by the Liberals, and up to now the laxest in Canada — will be changed to give a larger role to the labour board and restore the “appropriate balance between employer speech and the prevention of undue interference with employee choice,” in the words of the review panel.

Other changes are also intended to make it easier for workers to unionize. Signed cards to unionize, for example, were only valid for 90 days — if a drive lasted longer than that, organizers had to repeat the process. That’s changed to 180 days, which the panel said should provide a fairer chance for workers in a number of separate, small locations — typically hard to organize — to decide on unionization.

The changes to the law reduce the ability of companies to hire contract agencies to provide their employees and then cancel the contracts if the employees decided to form a union. The practice has been widely abused, as workers have organized, negotiated a contract, and then been fired and forced to apply for their own jobs, often at lower pay, and start the process all over again.

These changes are useful. But they don’t go far enough to address what the review panel called the “continuing erosion of middle-class jobs, increasing precarity and polarization between relatively low-paid precarious work and highly-paid skilled workers, and fewer middle-skilled jobs.”

For example, very few fast food workers are in a union giving them the ability to negotiate working conditions and wages with the employer. It’s tough to organize a lot of small sites with few employees and high turnover, even if the people are all working for a handful of giant corporations or their franchisees.

Sectoral bargaining — proposed in a 1992 review of the labour code — would increase the ability of workers in certain sectors to organize. Instead of separate union organizing drives and contract negotiations for each fast food outlet, a union could represent all workers in the sector across a region (as long as employees had made the decision to unionize).

The panel called for more study of the idea, which doesn’t much help workers today.

To be clear, this isn’t about bad bosses — either union or management, depending on your perspective. While there are lots of collaborative relationships between managers and unions, the reality is that employers want the work done to the required standard at the lowest cost. For corporate managers, that’s their responsibility. Last week, Loblaw shareholders voted down a proposal that the company at least study the implications of paying a living wage.

And unions want to advance the interests of their members, as the BCGEU emphasized in defending a government policy that will provide low-wage redress to unionized workers in the community social services sector, and leave out the people doing the same work — sometimes for the same organizations — who aren’t in a union.

It’s government's job to level the playing field, and it has failed miserably. About 40 per cent of Canadians are now in “non-standard” work arrangements, the panel’s report noted — part-time, contract work, self-employed, temporary work.

“The marked increase in non-standard work results in substantially less employment security and poorer working conditions,” it concluded. “Workers in non-standard employment often have little control over their working hours and face more occupational health and safety risks.”

The erosion of work quality, security and incomes has been a big factor in increasing inequality in Canada.

And somehow, we’ve paid too little attention to the slowly unfolding crisis, and the solutions that could be implemented.

The labour code changes are a start. But what’s really needed is a public demand that governments quit ignoring the steady, grinding decline in the quality of work available to Canadians.

Next, a look at whether new changes to B.C.’s Employment Standards Act will help ease the work-life crisis. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: