In the sociological literature on poverty, there are ample studies and papers about the ways that being poor impact the brain. Stress, malnutrition and exposure to the kinds of environmental contaminants that often accompany lower-income neighbourhoods (Flint’s lack of clean water or the poor air quality in schools around highways) can have serious neurological impacts on people living on the economic margins.

Less studied, however, is the impact that poverty — seeing it, knowing about it, thinking about it — has on the brains of people who are not poor.

This is also an important area of study, though, particularly as cities and states attempt to manoeuvre unprecedented wealth inequality and homelessness. Perceptions of poverty (and, as a result, perceptions of scarcity) have substantial impacts on the way we collectively think, act, vote and legislate.

And often, we don’t bother to examine them.

This is clear in community meetings about new affordable housing or homeless shelters, wherein self-proclaimed “concerned” neighbours begin every testimony with something along the lines of “I care about the homeless! I really do! But... ” and then follow their opener with something that expresses an unfounded bias about people living in poverty.

“... I’m worried about increases in crime.”

“... why do we have to pay for their housing?”

“... they’ll just trash it!”

“... how will I explain them to my children?”

These sentiments — which assume that homeless individuals are criminals, that they’re freeloaders, that their very existence is somehow damaging to children — are not based in research, nor do they account for the complexity of socioeconomic status. They are, instead, based on a reaction to poverty and scarcity that is intimately linked to our own survival mechanisms.

Just as humans grapple with implicit biases with regard to race, gender, size and a host of other differences, it’s clear from the research that does exist, as well as the anecdotal evidence playing out in communities around the country right now, that witnessing poverty and perceiving scarcity creates biases in people who are not poor.

But again, like racial- and gender-based discrimination, cognitive reactions aren’t an excuse for acting on those biases.

The sooner that those who have social (and literal) capital identify and combat these biases — as soon as they admit that they do, in fact, have negative feelings about the poor — the sooner we might be able to close the wealth gap through legislation, direct action and interventions.

Your brain on visible poverty

You might think that visible poverty — like tent encampments along a bike path — would prompt a tender response from sheltered individuals. You would be incorrect.

In actuality, research has found that increases in visible poverty result in an increase in wealth inequality. The Haves, in this case, are less charitable, less generous and less emotionally drawn to help when they can see just how little the Have-Nots have.

This is, I believe, linked to the perception of scarcity, and the idea that our economy is a zero-sum game. That is, if a poor person were to suddenly become not-poor, they may come for what you have and you might have less.

The companion to this is the assumption that when someone is poor, it must be because they deserve to stay that way. They must, fundamentally, be different than you are.

If not, there’s no clear answer as to why they are poor and you are not.

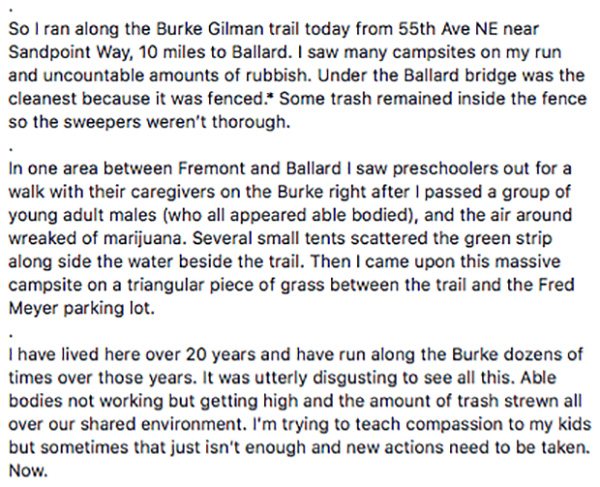

Like the woman who saw some (assumed) “able-bodied” men living in tents, many sheltered individuals make quick decisions about people they witness who are living in poverty. In the time it took to jog by some men, she determined, in her mind, their employment status, ability to find work that can adequately fund housing, disability status and much more.

The woman on her run doesn’t know whether these men do, in fact, work; they may be employed on the night shift and winding down after a long day. In fact, statistics from a City of Seattle survey of local unsheltered individuals found that more than 40 per cent did work — and another 20 per cent were unable to work.

She also didn’t know whether or not those jobs would be enough to support a person in Seattle. National Low Income Housing Coalition’s Out of Reach study found that in Washington state, a person needs to earn close to $27 per hour to afford a modest two-bedroom apartment. Seattle’s minimum wage is $15; the annual median income in the state is closer to $22 per hour.

Still, in spite of the fact that everyone in Seattle has felt the squeeze of increasing property taxes, a constricting job market, exploding health-care costs and a housing market that has priced out even upper-income residents, this woman did not think “oh dear, they must be a victim of circumstance.” Instead, she defaulted to “disgusted.”

This reaction is not atypical. In fact, the response to similar stimuli can even be seen in brain scans. In her book, Mind Over Money, psychologist Claudia Hammond describes numerous studies which looked specifically at cognitive reactions to images.

From the book:

Among the more compelling evidence are brain scans taken at Princeton University in 2006 by the neuroscientists Lasana Harris and Susan Fiske. They put volunteers in a scanner and showed them colour photographs of people belonging to different social groups. Some were clearly rich — for example, businessmen in fancy suits; while the appearance of others was such that they were obviously not just poor, but destitute.

When the volunteers looked at the pictures of homeless people, two-thirds were prepared to admit that their immediate reaction was one of disgust — which was interesting, and disturbing, in itself. But what interested Harris and Fiske more was the activity in the brain.

The brain scans had shown that when the volunteers were looking at pictures of rich people, the medial prefrontal cortex was activated. This was in line with previous research, which had demonstrated that it is this area of the brain which is activated whenever we see another person rather than an inanimate object. To put it crudely, the grey matter flashes up a message saying ‘same species here’ and that tells us that we should relate to this other thing in front of us as a fellow human being, rather than a lawn mower or a pigeon or whatever.

But when the people in the scanner were shown the pictures of homeless people the medial prefrontal cortex failed to do its thing. Yes, that’s right, the brains of the volunteers didn’t register that the shambling guy with the matted hair, the shapeless coat and the broken-down boots was another human being. Instead the areas of the brain associated with disgust were activated. A vulnerable person was dehumanized.

This is not surprising when a person digs into what visible poverty means to a human brain. When a person sees someone living in a tent, it signals to the brain that there is a lack of resources. This has documented impacts on cognitive function.

Writing for a 2018 study in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology, researchers from the University of British Columbia noted that “scarcity causes myopic and impulsive behaviour, prioritizing short-term gains over long-term gains.”

“Ironically,” they add, “scarcity can also result in a failure to notice beneficial information in the environment that alleviates the condition of scarcity.”

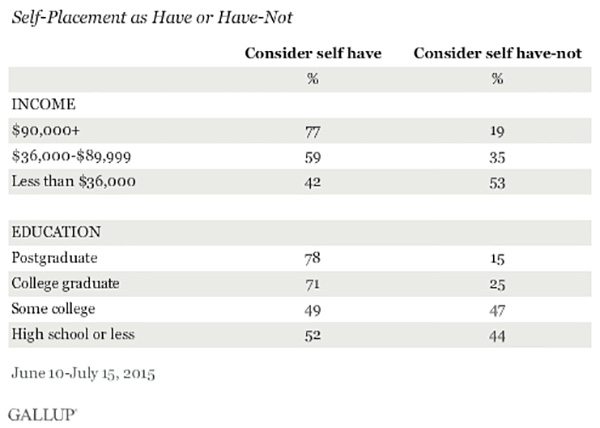

Of course, the woman on her jog isn’t actually experiencing scarcity herself in that moment; we can assume that because she’s lived in a relatively affluent neighbourhood of Seattle for 20 years that in fact she is fairly comfortable. Additionally, if she’s like most Americans, she likely considers herself a “Have.” But even just seeing poverty can trigger the scarcity response, the dehumanizing response, and so, create defensiveness and disgust.

These are survival reactions, but that doesn’t mean that they’re justified, or that they’re healthy, or that they’re acceptable. Our job as human beings — as neighbours, as people with hearts and souls — is to acknowledge these reactions, consider them and then override them. So why don’t we?

How we perpetuate negative perceptions of poor people (and make them seem OK)

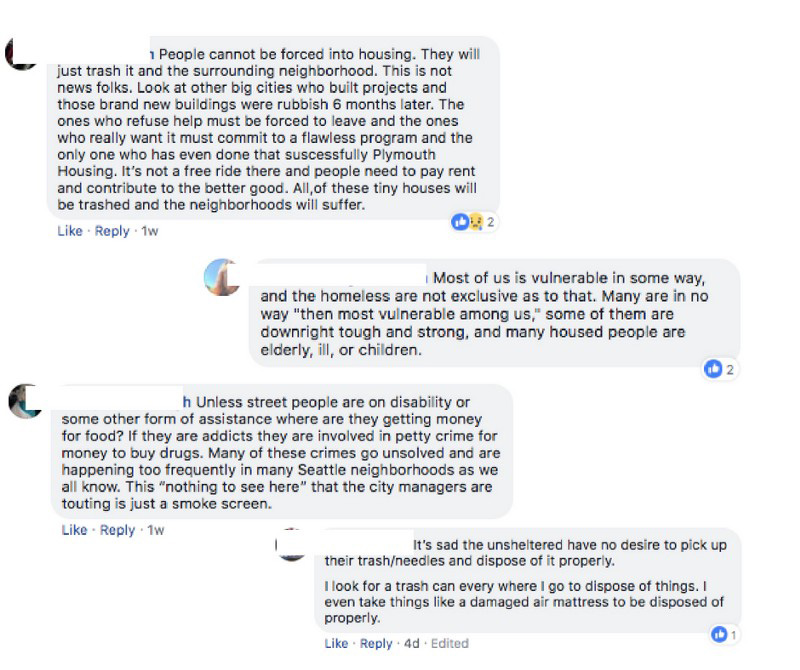

Bias toward the very poor is, in many ways, tolerated and even fostered in communities. The jogger in Seattle can rest easily at night knowing that she is not alone — her testimony in the Facebook group where she left it received accolades and nods of approval.

Disgust and contempt toward the very poor is, in reality, very common across the board, even among those who are poor. For many years, people of all income levels have been told, both implicitly and explicitly, that the poor are bad people and they should be looked down upon. And the message has been received.

This is not a supposition; it’s clear in data that’s been collected for years.

The Los Angeles Times conducted a survey of their readers in 2016 to gauge the collective opinion of lower-income individuals and families. What they found was a split opinion: 46 per cent of respondents above the poverty line said they believed the poor lacked basic skills. Only 31 per cent living below the poverty line believed that to be true.

Meanwhile, 61 per cent of respondents who lived above the poverty line believed that welfare benefits “make poor people dependent and encourage them to stay poor.”

Our collective perception of the poor hasn’t always been this way.

In 1985, the Los Angeles Times found that just 25 per cent of total respondents believe that welfare recipients want to stay on welfare. In 2016, that number had shot up to 36 per cent, with 38 per cent of respondents above the poverty line saying they believed it to be true.

This is, in part, because there have been substantial changes to the way that social services have been delivered, as well as a massive shift in how those services are portrayed by lawmakers and the media.

It began with Ronald Reagan’s deep cuts to services and his rhetoric that government assistance made people dependent on the taxpayer. It continued with the Clinton-era welfare reform package, which gave complete control over to the states and paved the way for crisis pregnancy centers and other non-poverty-related programs. Today, the torch is carried by Paul Ryan, who seems to have little regard or understanding for the fact that millions of Americans work and are still poor, thanks to deflated wages and gutted unions.

There has, for more than 30 years, been a resounding refrain that poverty is the fault of the poor, and that if you are not poor, you are somehow better, stronger, more capable and more deserving of food, housing and peace of mind.

That same stanza has been echoed, too, in the news media. Who can forget headlines about poor people who still have cellphones? The “Welfare Queens” and the grifters who have never worked a day in their lives but still get to sleep inside, on a bed, like a person? “Americans in ‘Poverty’ Typically Have Cellphones, Computers, TVs, VCRS, AC, Washers, Dryers and Microwaves,” read a 2013 CNS headline.

News organizations are quick to jump on any and all stories about crimes that include the poor as perpetrators — yet rarely do they report on the realities of life in poverty.

The 6 o’clock news is never led with stories about how systemic racism and historical oppression have kept the racial wealth gap wide open. There is no above-the-fold headline about how domestic violence — not a lack of skills or laziness — is frequently the singular reason that a woman becomes homeless, and a major contributor for the disproportionate number of LGBTQ youth on the streets.

This, for lack of a less overused work, normalizes these stereotypes about poor individuals, and confirms the biases that many sheltered people already hold. Their beliefs — their fears, their disgust — is reinforced each and every time their local news outlets focus on these elements of life outside, wholly ignoring the rest of the picture.

In normalizing this worldview, the cognitive, implicit biases about poverty and the very poor are changed from latent reactions to a deeply held, earnestly believed ideology. One that feels true, but that is still a little too icky to say aloud.

And so we get community meetings where participants state that they “really care about the homeless, but... ” and end with a thinly veiled threat to lawmakers to give them a place to stay. We get Facebook groups where neighbours freely post photos of people living outside and pass judgement, declare them criminals, express disgust — and then feel insulted when anyone insinuates that maybe, just maybe, they are being a bit judgmental.

Most of these people would never say, in as many words, that they hate the poor. Or that they think that the poor are bad people.

But maybe they should. Because then at least we could have an honest conversation about what to do next. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: