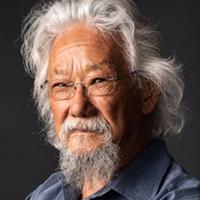

Walking with my grandson, Ryo, to daycare is one of my great joys. I get to remember how magical and wondrous the world appears through the innocent lens of childhood. In October as leaves fell, I explained how evergreens and deciduous trees differ.

“Bompa, are you a tree-hugger?” Ryo asked.

“Why are you asking that?” I replied.

“I dunno”, he answered. “One of the kids at daycare said his father calls you that.” Laughing, I told him tree-hugger is a term for people who love trees, and I would be proud to be called by that name.

He accepted my answer and turned his attention to other things. “What is that?” he asked, pointing to a dark clump in the naked branches. It was a bird’s nest. We spotted another smaller one in the same tree. “I didn’t know birds make their nests in these trees,” he said. As we began to search for nests in other trees, he mused, “I’m so glad the leaves fell off, because now we can see what the leaves covered up. Maybe we’ll see a squirrel’s nest.”

I tried to explain that the trees were shutting down for winter because the sun’s rays were getting weaker and, as photosynthesis slows, chlorophyll bleaches from the leaves to reveal other complex molecules that are red, yellow and other colours we see in fall leaves. (I didn’t use these terms because he’s only three!) So, I said, we get to enjoy the glorious foliage before the leaves fall. And then I explained what a wonderful gift autumn leaves are. People tend to treat fallen leaves as a nuisance, but as they decay, they return the complex molecules they’ve built up back to the soil, creating compost for themselves and a host of other organisms that will recycle those materials after winter.

As we rustled through the leaves, I described what a miracle trees are. Unlike animals that prepare nests in which to raise their young, trees spread their seeds in a variety of ways. Once a seed lands, it can’t pick up and move to a better place to germinate. Hiking through a forest, one can’t help but be amazed at trees growing out of rock, often jutting from a perpendicular cliff, with roots sent along cracks and crevices to find water and nutrients.

It’s humbling to think that each tree seed seeks the simplest of needs: air to provide carbon dioxide for the basic building blocks of the complex molecules (protein, nucleic acids, sugars, lipids) that will form its structures and carry out the basic metabolism of life; water to transport materials throughout the tree; and sunlight to provide energy that plants store in molecules for later needs.

Air, water and sunlight — what a modest inventory of primary needs. When I asked Ryo what we need to be happy and healthy, he started with food and water, then clothes, a house and toys. Soon, we wondered whether cars, phones, TV and computers are essentials. Ryo was amazed when I explained those undemanding trees also generate oxygen, a highly reactive element that transformed the atmosphere over hundreds of millions of years and continues to be produced by all green things in the ocean and on land so we can breathe. Ryo was boggled when I told him young trees are able to evade or tolerate insects, mammals and birds that eat tree shoots and leaves. I explained that trees may tower a hundred metres yet can withstand hurricanes, forest fires, earthquakes and floods. Ryo absorbed all this without surprise or the sense of wonder and gratitude I feel as an adult.

Before Ryo was born, his cousin, Ganhlaans, remarked when we were examining a large decorative plant, “Bompa, the leaves and stem are only the hair, you know. Most of the plant is underground.” I was amazed that, at four, he had such insight. Much of a tree is in its root system, which can be many kilometres in total length and, depending on circumstances and species, may extend far out laterally or deep down. I told Ryo that around each tiny rootlet of a tree is a gauzy wrapping of strands of mycorrhizal fungi that absorb water and nutrients and feed them to the tree in exchange for energy molecules made in the leaves. One tree’s roots also reach out to touch other tree roots, and they can help each other with water and nutrients.

He was excited when I said trees communicate not only with each other but other creatures, including us. “How do they talk?” he asked. I told him they communicate above ground through chemicals. “Here, smell these cedar leaves,” I said. He was amazed as I described how neighbouring trees can detect these volatile compounds in the air. They may signal danger from an attacking micro-organism or insect, for example, so the neighbours can prepare by making chemicals that bacteria or insects don’t like. Some of the chemicals resemble ones that act as signals in our brain or body.

That’s why Japan recognized shinrin-yoku or “forest bathing” as part of its health program in 1982. The Japanese have found that being near trees has a beneficial effect, stimulating the immune system, lowering blood pressure and heart rate, and relieving anxiety.

“Bompa, I’m glad you’re a tree-hugger, and now, I want to be a tree-hugger too,” Ryo concluded.

Children are plugged into their surroundings. Ryo is easily startled by noises I don’t even notice. “What is that?” he often asks as he smells, hears or sees things I no longer pay attention to. Like his mother when she was a child, Ryo likes to find the tiniest things — clam shells or crabs on the beach, tiny caterpillars or seeds in the woods. I long thought he possessed superior observational skills because he’s closer to the ground, but I know the reality is that I have grown older in a dense urban setting where I have damped down my senses to focus on what I’m doing. I see it on buses, where people wear earbuds, plugged into their phones, unconscious of other people or what’s going on around them.

When Ryo was about a year old, I spent a week taking care of him in Victoria, where my daughter and her husband lived. I had a routine walk of about three kilometres on a path shared by numerous bikers, joggers and walkers. One morning, I was delighted to see a large owl sitting on a low branch along the oceanfront. I got as close as I could to point it out to Ryo and to take pictures. Owls are marvelous animals that I have seldom seen, let alone gotten that close to in the daytime. Dozens of people passed by and not one paused to look up.

We live in a world shattered by the avalanche of information, entertainment and distraction provided by the digital revolution. But in this turbulent world, we neglect real people and the rest of nature.

Hence, my gratitude for my regular walks with Ryo. As is so often the case when spending time with children, I suspect he teaches me more than I teach him. ![]()

Read more: Health, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: