If you’d been a member of the British aristocracy a century ago, or a noteworthy recent political figure or – even better – a person well-connected to the Vancouver Parks Board, you’d have stood a chance, admittedly small, to have a Vancouver park named after you. From Great Britain’s Lord Stanley (Stanley Park) to a late Vancouver mayor (Art Phillips Park), there’s been a long tradition of putting important public figures’ names to places. However, there are categories of important people and organizations that tend to get ignored when prospective Vancouver park names are discussed. These are the people and groups that have stood on the wrong side of history: ethnic minorities, artists, leftists, popular celebrities and of course, women. It’s the way things have worked since Cheops got his pyramid.

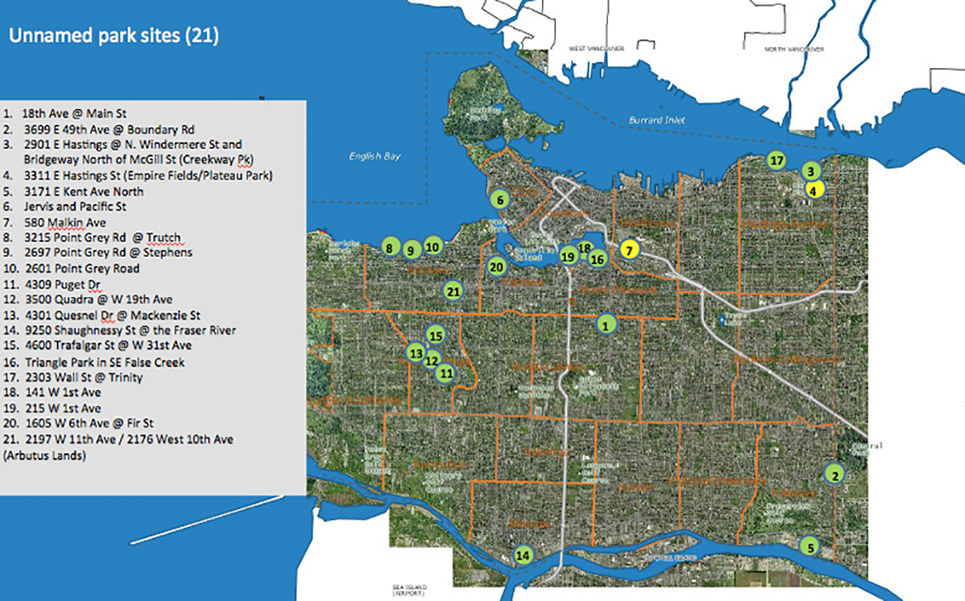

In order to rectify, in some small way, this imbalance between the insiders and outliers, the Vancouver Parks Board has just approved a Park Naming Committee, tasked to solicit from the public possible names for the city’s 21 currently unnamed civic parks. (See map below.) The process will begin with the selection of a new name for East Vancouver’s Empire Fields, known to most as the PNE. Then, in a multi-year series of subsequent public solicitations and Parks Board decisions, the remaining parks will acquire names.

In a five-page document dated July 7, the Parks Board laid out the process that will unfold in the years ahead. The document includes names of the Park Naming Committee’s proposed members (and its first neighbourhood advisory group), plus guidelines these people are to follow in selecting park names. The committee, it says, should first consider an easily recognizable geographic location – a well-known adjacent street, say, or a natural feature – in choosing an unnamed park’s name. Or, if these don’t exist, the committee can turn to the name of a historical event or important person, preferably, but not necessarily, one who’s being recognized posthumously.

But here’s where the guidelines get curious. A close reading of the committee’s mandate says choices should reflect the names of “persons important to the Parks Board,” or “persons having made substantial contributions to the Parks Board,” or “a living person who has a lifetime achievement consistent with the Parks Board mandate.” What if the person or event has had no connection to the Parks Board, but has had a monumental connection to Vancouver itself? Like Greenpeace, the world’s largest environmental organization, founded in Vancouver in 1971? What about architect Arthur Erickson? Or David Suzuki? Or the writer/broadcaster Chuck Davis, author of 11 books on Vancouver? Or Strathcona’s almost unknown Mary Chan who, decades ago, led a critically important and successful 17-year-long fight against a proposed freeway through downtown Vancouver?

Too often, as the current names of the city’s 200 or so parks demonstrate, the Parks Board choices have been similar to those made to select members for the Canadian Senate. Having political connections, good name visibility and demonstrated service to the ruling regime, then: Bob’s your uncle! Vancouver has, in fact, at least 10 parks named for Parks Board officials, plus 25 or so more named for local political figures and their provincial/federal pals. In Parks Board history and in its latest naming guidelines, the scale seems clearly tipped towards advancing those that have Parks Board connections.

Says Paola Qualizza, chair of the Vancouver Public Space Network and one of the Naming Committee’s members, “What’s been missing in the past are the names of ethnic people, First Nations and women. Especially women! We need to make up for all the park names which feature wealthy, white, male political people.” She believes that the city has today reached an important social turning point. And that – in a belated Occupy Wall Street sort of way – the time has come to recognize the contributions of the less-powerful and often overlooked 99 per cent, so that Vancouver’s street names, park names and civic facility names better reflect 21st-century class and multicultural realities.

‘Time to catch up’

In politics, however, it’s easy to be cynical. Good intentions confront special interests; optimism succumbs to realpolitik. In 2007, the Vancouver Parks Board established a Park Naming Policy that called for public input into future parks’ names. In 2008, two Vancouver parks’ names – Ebisu Park and Oak Meadows Park – were chosen based on an open, public naming process. Since then – during the last eight years – not a single park’s name has gone through this apparently abandoned public involvement procedure.

Parks Board chair, Sarah Kirby-Yung, cannot explain why her predecessors halted public engagement in the naming of Vancouver’s parks or why there are currently 21 unnamed parks. She says unequivocally, “There’s such a backlog! The board feels it’s time to catch up. The public should have a say.” She agrees with Qualizza that certain groups – for example, First Nations and their traditional sites – need to be commemorated more. This process will begin with a new name for Empire Fields (a.k.a. the PNE), to be announced this October. It will mark the resurrection of good Parks Board intentions belatedly re-applied.

In fact, planning is now underway – with a soft-launch tentatively planned in September at a new park at 17th and Yukon – to invite the public to join in the naming of future parks. In each neighbourhood where an unnamed parksite exists, local civic groups will be asked to solicit names that area citizens feel might be appropriate for the park. Parksites will be postered, asking for input. Online balloting will occur. The Naming Commitee will then shortlist suggestions for final board approval.

There is a lot to make up for. As Justin Trudeau said, defending the 50-per cent female composition of his new cabinet: “It’s 2015.” A thorough perusal of the list of the city’s current parks, including the origins of many of their names, reveals these not-surprising facts. The 50 or so Vancouver parks named after men exceed by a factor of 10 the number of parks – precisely five – named after women. The total number of park names attached to a significant Vancouver cultural figure is this: one. Delamont Park, located at 7th and Arbutus, is named for a much-loved, mid-20th century community bandleader. The total number of park names that reflect the city’s Asian communities – Chinese, South Asian, Filipino, East and Southeast Asian – is also one: Yaletown’s David Lam Park, named for the province’s former lieutenant-governor. (The one curious exception to these patterns is the brand new Jim Deva Plaza, at Davie and Bute, which honours the Little Sister’s bookstore owner/activist Jim Deva, who fought against government censorship and for LGBQ2+ rights for 20 years.)

One of the parks soon-to-be named – a process currently stymied in discussions with First Nations – is so-called Trillium Park, located on a three-hectare section of False Creek Flats just south of Strathcona. Had not Strathcona resident Mary Chan decided to fight the 1960s, eight-lane freeway proposed for downtown Vancouver – rallying hundreds of Chinese residents initially and later joined by thousands more concerned citizens – most of the city’s heritage districts would have been demolished. Instead of an elevated highway through East Vancouver, Strathcona, Chinatown, Gastown and along the Coal Harbour waterfront, ending in a massive bridge over Stanley Park, Vancouver is today the only major North American city not to have had an ugly freeway driven into its heart.

“She was born in the year of the Fire Dragon,” says daughter, Shirley Chan, of her mother. “She had fire. She was a battler. She believed in justice. She refused to accept the destruction of her community.” Mary Chan died in 2002, falling down the back stairs of the Strathcona home she’d once fought to save. And as irony would have it, the proposed freeway would have passed directly over the site of today’s Trillium Park. Were it to be renamed Mary Chan Park, it would mark a significant step in an overdue process to redress the omissions of the past. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: