My friend Hughes describes the ageing process not as a slope (however steep or gradual), but as a series of steps on a staircase. You're ambling along, feeling more or less stable, doing what you normally do, and... Ker-chunk!

What the hell was that? You ask, splayed out on your back, looking up at the step you once occupied. Then you realize that you now occupy the next step down, on the way to -- oh, let's call it the basement.

Don't get me wrong. This step down, this abrupt plummet, is not a preordained event. Proper exercise, diet, attitude, friends, pets, can lengthen the tread or lower the rise; the step can be less frequent, the drop less vertiginous.

But even so, the steps only go one way.

Nobody ever died of nothing. Habit, ignorance, DNA, bad luck or all four catch up with you at some point, and Ker-chunk! -- you're in the hospital.

Thanks to a population bulge and an increase in treatable ailments, more and more Canadians in their sixties are experiencing the Canadian medical system for the first time -- getting an inside look at the machine our parents created a half-century ago, when we were teenagers and Medicare became the law of the land.

My inner carbuncle

I recently acquired a new family doctor. Dr. M. is in her thirties, a former anaesthetist who took a less edgy position in order to raise three young children. She made me nervous: blood pressure easily up 20 systolic.

First, Dr. M took an inventory of ''pre-existent conditions,'' the ones that keep people from collecting on private insurance. Our next order of business was a general check-up, which Medicare pays for biannually. Out came the stethoscope, the blood pressure machine and a bit of poking, but mostly it concerned what the lab thought of my blood -- which came off rather well, swishing through open arteries, unhindered by plaque.

Only one test produced a question mark. It resulted in my first colonoscopy.

The current thinking in intestinal circles is that things called polyps are precursors to bowel cancer; that if you eliminate the little rascals, you can head off something very nasty.

Fine with me. Friends underwent the procedure, which sounded like vicarious spelunking. You're given something nice through a needle, then you get to watch a screen while a mini-camera prowls your intestine. If they find a polyp (sounds like a sea-creature), they ''snip it off.''

And so we enter the land of Dr. G, a gastroenterologist -- a neat, affable man who would look good in a bow tie, like a Harvard attorney.

A fortnight later I am not so well dressed. Dr. G has me on a long table in the foetal position, staring at a video screen, wearing a backless blue gown and thigh-length socks like a Shakespearian faerie while a nurse with an East European accent and a depressing resemblance to Uma Thurman assists Dr. G in shoving a camera on the end of a tube up where the sun never shines.

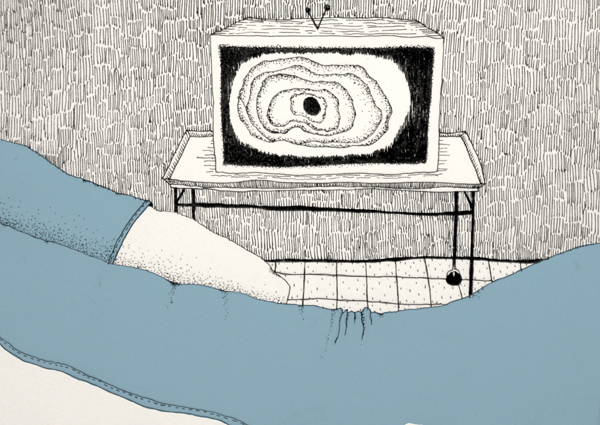

They gave me something pleasant enough that I would not be allowed to drive home, which lent a gauze of unreality to the monitor as the camera navigated a pink tunnel, like a worm hole from the Dune trilogy, twisting and turning this way and that -- and then paused before a dark red lump. (The word ''carbuncle'' came to mind. I had never actually seen a carbuncle, but read about them in Dickens novels, where they appeared on the noses of elderly drunkards.)

''My goodness, would you look at that,'' said Dr. G, and I knew this wasn't leading anywhere I wanted to go.

Lounging in the recovery room, fully clothed, slightly stoned, I watched Dr. G execute a simple drawing: Evidently, my polyp was located at the cusp of my small intestine, where they could not simply ''snip it off'' but would have to ''go in there.'' With a ball-point pen, he illustrated how the surgeon would cut out a section of small and large intestine, then sew it all back together.

''Do you have any questions?'' he asked.

''It looks like a plumber replacing a T-joint,'' I said.

''Exactly,'' he replied, pleased. ''It's a simple procedure.''

I recalled my attempts at do-it-yourself plumbing. Plumbing is seldom as simple as it looks.

''How will this affect my, er, personal habits?''

''Oh that will be fine. There might be a certain urgency.''

A certain urgency.

''Just to complete the picture,'' I said, ''what happens if I don't do anything at all?''

''Assuming it's not malignant, you might be fine but at some point your small intestine will become completely blocked, which would be an emergency. And you would be older, and maybe not in as good shape as you're in now.''

Older, and a few steps down the staircase.

We all know the ''complications'' that occur with the elderly. The heart stops because it can't take the anaesthetic, and you die; or you get an infection, a bug that a young man would flick off like a gnat, and you die; or you contract pneumonia -- no big deal for the young but the ''old man's friend'' -- meaning, you die.

Doctors present you with choices, but there always seems to be an obvious answer.

Dr. G assured me that my surgeon, Dr. A, was at the forefront of the laparoscopic technique, which has a faster recovery time. As soon as I got home, I did a search.

Laparoscopic surgery, also called minimally invasive surgery or keyhole surgery, is a modern surgical technique in which operations in the abdomen are performed through small incisions, as opposed to the larger incisions needed in traditional laparotomy. -- Wikipedia

Papillose

On the way home from a medical consultation, inevitably you think of something you wish you'd asked; in my case it was: Given the pace of medical innovation, why can't one put a bet on future improvement?

Seemingly you can't. The scientific method deals with established fact, evidence, calculations. Scientists don't place bets on future trends in science itself, the way hedge fund traders do with stocks. Put in TSE terms, when investing in a medical procedure, you can only sell short.

Within a fortnight I was sitting next to a computer desk with a general surgeon, Dr. A, a trim man with the affect of a compassionate technician -- the Italian mechanic who tells you that the new clutch for the car you worship will cost $9,000.

Dr. A took pen and paper and drew exactly the same drawing Dr. G drew. I pointed at the junction between the small and large intestine: ''I understand there's a valve there.''

''You don't need the valve,'' Dr. A assures me. ''Though there may be a certain urgency for a while.'' A certain urgency.

The ileocecal valve is a papillose structure...situated at the junction of the small intestine and the large intestine. Its critical function is to limit the reflux of colonic contents into the small intestine. -- Wikipedia

Health food websites say the ileocecal valve is crucial to prevent ''toxins'' from re-entering the system, while patient discussion groups complain of ''decades of sprinting to the bathroom.''

Medical websites say that's nonsense, other functions take up the, er, slack.

On this one I tend to believe the scientists, if only because these same ''alternative medicine'' websites envisage pounds of fecal matter plastered like fibreglass on the intestinal walls, necessitating enemas aplenty. Thanks to Dr. G, I saw my intestinal walls with my own eyes and they were clean as a whistle.

When our previous family doctor retired, for medical issues I started consulting Wikipedia -- the site for people who are only slightly interested in a subject, who just want the general idea. My friend Hughes thinks that consulting the internet about medical issues opens a Pandora's box of confusion and paranoia.

I agree with him but I do it anyway. I see it as part of the dialogue between science, which asserts a truth for everyone, and the individual, who seeks a truth that may only apply to me.

My new GP is an intuitive woman who knows more about me than she lets on. Even so, Dr. M is bounded by margins set by precedent and also by the calculations of the Canadian medical bureaucracy. Given her age, she would see this as the normal way to practise medicine -- less to do with direct observation than with the computation of actuarial statistics. She sends me to a lab, which analyzes my blood and reports the numbers; she then compares my numbers with statistical data and either does nothing, or prescribes something, or refers me to a specialist.

In the examination room, Dr. M often consults a machine like a fat pocket calculator, entering my variables and waiting for the screen to answer. It's not the art or science of medicine, more like the math of medicine.

According to the machine, I have a 20 per cent chance of suffering a heart attack in the next 10 years -- but is that good or bad? How does that compare with my chance of having prostate cancer, or slipping in the tub and banging my head? What does it mean?

The question snaps me back to the 1960s, when Medicare was a controversial topic, especially among physicians -- and it wasn't all about the profit motive.

Some doctors were all for Medicare -- particularly those who could remember the Depression, when they were as likely to be paid in eggs as in cash. Others held the view that Medicare would effectively change their status, from a self-employed professional to an employee under contract -- which, in turn, would gradually transform the patient from a person into a number.

This view of medical practice goes back to an era when Canadian doctors for the most part worked in villages and towns. They attended church and the curling club and the Rotary Club supper. They knew their patients, having seen them not only in the examining room but also on the street, and a whiff of rumour reached a doctor's nose as soon as anyone – towns are full of secrets that everyone knows.

Of course the small-town model was unsustainable -- our population has doubled since the 1950s, cities are the economic and cultural drivers, and who knows one's neighbours? It would take a genius of social engineering with a computer the size of Manitoba to design a system that might translate the small-town relationship into another context.

Meanwhile, as pundits debate ''wait-times'' and ''individual choice,'' Medicare has evolved into Canada's existential statement to itself and the world: Everybody gets sick or injured. The wait-list is everyone.

But where is the wait-list when you want one?

My surgeon, Dr. A, dated my wait-time at six or seven months. Fine by me, with no symptoms and in no hurry to be cut open.

Then a week later, I received an unexpected phone call: Could I come in for my procedure in 10 days?

Tomorrow, the second in this three-part series: The Procedure: In Hot Polyp Pursuit. In which our narrator contemplates the great beyond while a team probes his not great behind. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: