Each year our city plays host to 10 times more tourists -- six million of them -- than our year-round population. They come to see what we who live here see everyday: Stanley Park, Gastown, gleaming glass towers and nature at its most spectacular.

But do those of us who live here see the city through a different lens? Are different parts of the city more important to us than the tourist attractions? The 17 students in our class wanted to find out.

A warning before we start: there is nothing quite so arrogant as making the claim that you understand what makes a place special to someone else. Each person has their own perceptions, perceptions influenced by their own routine, their own history, their own joys, their own struggles. For one person, walking four blocks along Commercial Drive for the thousandth time and through perpetual drizzle might induce an uncontrollable burst of hate for this raged city, its expense and its perpetual gloom; but at the exact same moment a different person, with a different life and a different mindset, might delight in what they perceive as the Drive's eclectic collisions of cultures, ages, lifestyles and culinary attractions -- the drizzle-sheened sidewalks making the reflected storefront neon all the more vivid.

Nevertheless, as is the case with most deadline-driven studio projects, students do what they can within the time allowed. With that extensive caveat in place, and on behalf of the class, we offer the following "rules" they came up with -- rules for protecting our "common place."

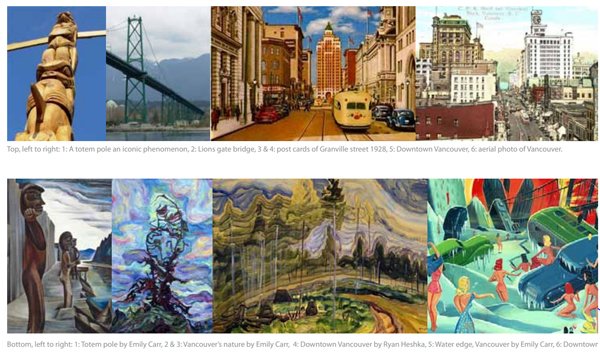

1. Vancouver, the City of Nature, by Neda Roohnia:

First a quote from the late Kevin Lynch, who wrote about what makes cities special in The Image of the City: "At every moment there is more than the eye can see, more than the ear can hear, a setting or a view wanting to be explored." While not speaking specifically about Vancouver, he could have been. Because of its voluptuous landscape setting, Vancouver always presents more than we can take in. It's so obvious, but so true: in the words of the slogan, Vancouver is spectacular by nature. The rule must be this: keep a balance between the human built forms of the city and the spectacular forms of nature. But beyond that? Change things slowly. There are so many little things, intimate places, that ordinary residents connect to. While it seems like a contradiction, somehow we must make changes slowly to this fast-changing city.

2. Favour the "exchange" city over the "mobility" city, by Patrick Chan:

Richard Florida, author of many books about the life and purpose of cities -- the most famous of them being The Rise of the Creative Class -- claims that the most successful and most exciting cities to live in are "exchange cities." Exchange cities are the opposite of mobility cities. Mobility cities you just move through without friction. Exchange cities slow you down. They have many more intersections, places to connect, places for accidental meetings, places for businesses to start, deals to be made, lovers to meet. In our city we have some mobility streets, like Kingsway. But right now it's not the best place for exchanges. Kingsway has long blocks and fewer crossing points. It has too many strip commercial sites where parking gets in between sidewalks and front doors. Kingsway is too noisy, designed for cars, not people.

On the other hand we have many good exchange streets, like Main Street. Main Street has very short blocks and very frequent intersections, creating hundreds of places to cross, catch a bus, or enjoy the sun. Our rule is protect these exchange city qualities in streets where they exist, and add them to streets where they don't.

3. Respect the corridors, by Mary Wong:

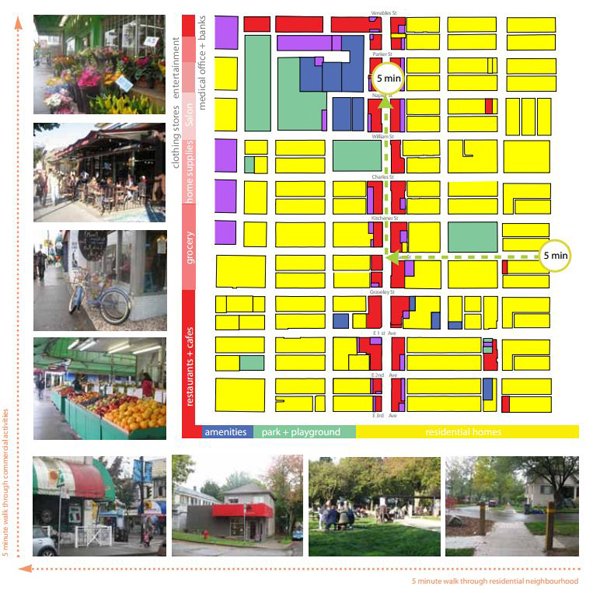

Corridors are showcases for what a neighbourhood is. Quiet neighbourhood streets all flow to the corridors. The corridors are the centre of life for the residents who live within a short walk, a walk they repeat thousands of times. Continuous commercial strips are like a dance with flowing music. The "music" of human activity flows out of the commercial spaces and blends into the street. Where two corridors meet, a pronounced place of gathering is created. Restaurants wrap their seating around corners framing an entrance to the surrounding neighbourhoods. Buildings include recessed spaces with engaging store displays enhancing the pedestrian experience. Some store owners happily colonize this space by spilling their goods and services onto the sidewalk.

4. Emphasize the centres in the system, by Peiqi Wang:

Some places in our city are special centres of activity, revered by their users and lucrative for merchants: Granville Island, the intersection of Burrard and Robson, Kerrisdale's vivid "Main Street" at 41st and Yew. The best of these are marked by a gateway, creating an inside and outside and a centre within the centre. Think of wide West Boulevard providing a green gate for Kerrisdale, or the underside of the Burrard Street bridge making an oh-so-obvious gateway for Granville Island. For the most part, in our city built around the streetcar, our centres occur as places of special energy in a consistent matrix of evenly-spaced arterial streets.

5. Make places that we can attach to, by James Godwin:

Places don't need to be tourist attractions for us to attach to. What we need is a variety of services and experiences as part of our everyday world. In our city almost all of these common places are on arterials. Some work better than others. Commercial Drive is a classic example of a place to attach to. Residents are passionate about "The Drive" and identify with it deeply. Other places like East Broadway do not attract that degree of affection. Why? Perhaps it is the subtle things, like the length of store frontages, the interruption of the sidewalk for parking lots, the width of the street and the difficulty in crossing it. The noise. Perhaps if it was easier to cross, if there were more storefronts, if the sidewalks were wider, if the cars had to stop for pedestrians instead of the other way around, we'd feel more attached.

6. Respect the symbols of place and the settings they rest in, by Lisa Lang:

The symbols of place range from the monumental scale of the North Shore Lions that claim the terminus of almost every view to the north, to the giant bowling pin at the Ridge Bowling Alley on Arbutus and 16th Street. Symbols of place are the hardest things to identify and protect, as the more intimate ones are often commonplace items that we have lived with for decades. Historic structures are an obvious example of this precious connection to the past, but not the only ones. Finally, all too often we forget that symbols of place always have a setting. The Cenotaph at Victory Square depends on the setting of the tree-edged grassy triangle of Victory Square park for its power. It also depends on the buildings that surround the square on all sides. Absent this enclosure, it would have fallen victim to the feeling of abandonment that afflicts the Terry Fox memorial at BC Place Stadium.

7. Accommodate the changing lifestyles of the young and the new, by Cindy Hung:

Our city is changing in dramatic ways. Vancouver has proportionately more single people than almost any other place in B.C. We also welcome immigrants from around the world. Our culture, once characterized by the privacy of the home and the primacy of the family, is now shifted to one where more and more of our time is spent in the public realm. Young people now haunt cafés at all hours, staring at laptop screens in seeming isolation, but in actual fact feeling a human connection to others of their tribe. Asian grocers spill their wares out into the street. Sidewalks, once places for a minimum of polite interaction, are now a riot of teenage enthusiasm, al fresco dining and cultural collisions. Our streets, buildings and especially our sidewalks can barely contain the din. Give over more space to this, and ensure a free flow of space and activity between buildings and streets.

Back to the streets

These seven rules are our humble contribution to an ongoing conversation about what makes this place special. Our study left us with more questions than answers, but with at least a few insights worth sharing. The reader who has plowed through our first four articles may see a pattern emerging here. Perhaps as a consequence of our previous studies -- focused on the most practical locations for affordable housing, zero-GHG transit and sustainable energy use -- our gaze kept returning to our city's arterial streets.

Our study reinforced the notion that our sense of place and how we define ourselves by neighbourhoods has a lot to do with our commonplace arterial streets. Both the physical arrangement of our arterial streets and the activities that now line them are a legacy of the streetcar period. We completed the study more convinced than ever that our many arterial streets constituted the very heart of the sense of place for city residents, and that we should do everything we could to ensure that they are protected and enhanced.

Next week: The conclusion to this series -- four big "convenience truths."

[Tags: Urban Planning and Architecture.] ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: