When salmon feedlots came to British Columbia, a pound of fresh salmon was worth $9 in mid-winter. This triggered gold-rush behavior, which devaluated farm salmon to a low-priced commodity. It is easy to see why people got into raising salmon, but when I began to investigate the relationship between salmon feedlots and the Fraser sockeye crash, I made an unexpected discovery. B.C. feedlot salmon cannot meet world market standards for sustainable practices, they have too many secrets. When government made it possible for salmon feedlots to operate outside the Constitution of Canada, it sealed the fate of both the industry and the wild salmon, both of which they were tasked to protect.

The first step set the course to disaster

Salmon feedlots should never have happened to Canada because they violate the Constitution by privatizing ocean spaces and exerting ownership over fish in sovereign marine waters. For reasons we are left to guess, government decided to overlook this and began beavering away on a patchwork of poorly considered fixes to overcome this inconvenience.

In 1989, the then federal minister of fisheries, Tom Siddon, and the provincial minister of agriculture and fisheries, John Savage, signed an unlawful Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) transferring salmon feedlot management to the provincial government, even though the industry clearly exists in federal jurisdiction -- the ocean. While this disguised them as "farms," a few outstanding irregularities persisted. A farmer doesn't need a hunting licence to recapture his cow, but a salmon "farmer" needs a federal fishing licence to recapture his livestock. This means they don't own the fish, they are not a farm and should have to abide by the Fisheries Act.

The Pacific Fishery Regulations 1993 fixed this little problem by exempting provincially licensed aquaculture from all the fishing regulations in the Fisheries Act. This allowed the industry to drift further from the legal standards set in Canada to protect wild fish for all Canadians. The Federal Fisheries and Ocean Canada (DFO) was effectively forced to stand down when they were assigned the dual mandate to protect wild fish and promote (not just tolerate) salmon feedlots. This meant that every time push came to shove, wild fish lost because the corporate feedlots were more powerful than members of the public.

In 2009, the B.C. Supreme Court struck down the unlawful MOU transaction and gave government a year to put salmon feedlots back where they belonged into federal hands. But government and industry have been outside the law for so long bad habits have become entrenched and they missed the deadline. The court granted an extension, but the problem is even bigger. Salmon feedlots cannot meet even the most basic international requirement to report certain diseases and this is impacting their markets. The Canadian public should consider itself warned when this powerfully profit-motivated industry accepts a "lesser market" in exchange for secrecy

Government cover-up and the Fraser sockeye

Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis (IHN) virus is called Sockeye Disease because it is deadly to this species. In feedlots, animals sharing body fluids spread pathogens rapidly, super-charging the surrounds with disease at levels wild animals have never survived. When a feedlot is wiped out by disease, they are replaced, but when wild fish are wiped out, they are lost.

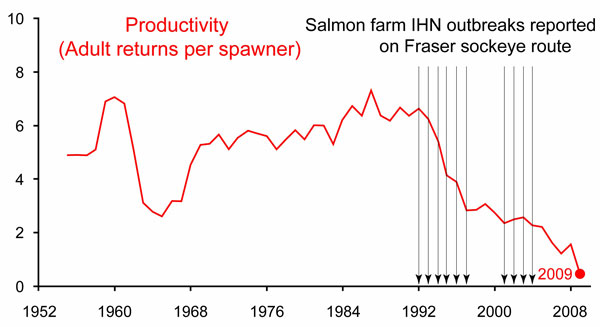

IHN epidemics began in the salmon feedlots in July 1992 in Okisollo Channel, one of the narrowest migration passages used by Fraser sockeye. This is the same year the Fraser River sockeye began declining.

Government emails suggest a marine feedlot site in Okisollo Channel was stocked with IHN infected Atlantic salmon smolts from a Vancouver Island Hatchery. The provincial Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food (now named the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands) and provincial Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks had an agreement to share fish disease information, but the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food kept this epidemic a secret.

When the province's Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks found out two months later, they wanted the DFO, a department of the federal government, to protect the sockeye and the steelhead in the area. But as per the unlawful MOU giving the province jurisdiction over salmon feedlot management, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food ruled, DFO stood down and they let the diseased salmon stay in the feedlot. The virus spread to 13 feedlots within 20 kilometres in four years (St-Hilaire et al. 2002). As eight generations of Fraser sockeye swam through this viral soup their numbers fell rapidly.

Eight months into this epidemic, DFO published research on IHN virus (Traxler et al. 1993) reporting:

- IHN "has caused severe losses among sockeye"

- Sockeye can become infected by "cohabitation" with infected Atlantic salmon

- Introduction of "infected fish to netpens should be avoided"

While these findings had to be a red flag, Traxler wrote "problems due to IHN in netpens have not yet occurred." How could a fish pathologist observe Canada's most valuable wild fish stock swimming through a viral epidemic that was spreading to millions of Atlantic salmon and report there was no problem? This paper should have triggered mandatory reporting, inspection and culling of IHN infected feedlot salmon. Instead, DFO and the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food did not inconvenience the feedlot owners. Northbound sockeye passing through the feedlot effluent would have become IHN carriers into Rivers Inlet and Skeena stocks.

There have been "four waves" of IHN outbreaks, according to Canadian Food Inspection Agency, in feedlots on the Fraser sockeye migratory corridor right to the central coast. Saksida (2006) reports "Farming practices themselves contributed significantly to the spread between farms." While the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food and DFO did not acknowledge the threat to wild salmon, somehow the B.C. Supreme Court understood, issuing an injunction preventing vessels carrying the IHN-infected feedlot salmon from entering the Fraser River.

The public record chronicles a group of men in the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks who tried to protect our wild salmon from the feedlots. As soon as the BC Liberal government achieved office they began disassembling the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. Today, there is no ministry championing the people's salmon.

The pattern of the Fraser sockeye decline is stark. Only the Fraser stocks that migrate past salmon farms are in decline. The Fraser Harrison sockeye, which migrate via the Strait of Juan de Fuca thus avoiding salmon feedlots, are thriving. The neighbouring sockeye stocks that do not encounter feedlots are also thriving (Sproat Lake, the Okanagan and Columbia Rivers). Salmon feedlot disease records are essential to understanding why the Fraser sockeye are in free-fall.

Disease reporting, not at all what we asked for

The B.C. Salmon Aquaculture Review in 1997 recommended legislated, comprehensive disease surveillance of salmon feedlots with "First Nations, industry, community fishers and wild fishery organizations."

The Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans in 2001 recommended "early detection and mandatory reporting of diseases for farmed aquatic animals."

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food and DFO have clearly been told public disease reporting must occur. But imagine if First Nations and fishermen had been aware that IHN was raging through the migratory corridors of the collapsing Fraser sockeye? I think some did consider this. In 2001, Bud Graham of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food and the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association signed a non-binding "Letter of Understanding" outlining a voluntary disease reporting scheme, outside any legislation, into a database "with restricted access and a series of firewalls to maintain individual company confidentiality."

Salmon feedlot disease became so top-secret the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food's own inspectors were cut out of the loop. How could they audit the feedlots without this basic information? The agreement did give access to the provincial vets required to write drug prescriptions.

The Freedom of Information fracas

When the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands (formerly known as the Ministry of Agriculture, Fish and Food) had its salmon feedlot disease records requested under Freedom of Information legislation (FOI), the ministry stalled for six years. When the FOI Commissioners Office stepped in and investigated, the feedlot companies threatened government -- if the FOI was honoured, they would never report their diseases again. The Freedom of Information Commissioner prevailed and forced the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands to release the information. So, are the feedlots owners making good on their threat? A second FOI request came in for the recent disease records and this is going to test the unraveling regulatory mess. What are the feedlots to do now? The Ministry of Agriculture and Lands bought time by flatly refusing the FOI, even in the face of the recent decision. And the stand-off continues.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency takes a swing at this

Twenty years after stepping outside the Constitution of Canada, the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands is diligently protecting the feedlot owners, most of who are Norwegian, from the public.

But what about the world community and their pesky demand for sustainability? The Canadian Food Inspection Agency reports that Canada has not fully met "any" of the fish disease reporting requirements set by the World Health Organization for Animal Health, to which Canada is a signatory. As a result, they report, Canada is now subject to a lesser market due to a lax regulatory framework.

Oops.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency stepped into this battlefield in December 2009 listing 23 aquatic pathogens as "Immediately Notifiable Diseases," including IHN, which the OIE has always considered a reportable disease.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Lands refuses to answer if IHN is now reportable or not.

This can't be about fish

There is a major fault line opening here with no internal fix possible. While the salmon feedlot industry has taken the stand that it will not report disease, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency regulated mandatory reporting of 23 fish diseases to meet market standards. While the federal government is going to inherit this mess, they are not ready and so it remains adhered to the BC Liberals, like a sea louse.

An industry that cannot respond to its own market is not viable. All of this raises the question, what is going on in these feedlots that they are so scared of telling us about? And how will the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands respond to the Cohen Inquiry which cannot make a credible assessment of the Fraser sockeye decline without the ministry's salmon feedlot disease database.

As the lump under the carpet keeps growing and is now crawling around, the BC Liberals and federal Conservatives keep telling us this is good for us. They like to say this is about jobs, even though the salmon farmers are mechanizing away those jobs away to lower costs. Government never mentions the 40,000 people that depend on wild salmon through the $2 billion fishing and wilderness tourism industries.

I would like to suggest none of this is about fish. It looks like a mistake with no exit strategy. Someone did not do a full risk analysis on that first step off the tracks in 1989. Wild salmon are in the way of massive industrialization by foreign companies and someone probably thought the public could be weaned off wild salmon with feedlot salmon.

The solution

The salmon feedlots are in a catch-22. Either they release their disease information and take their place among sustainable seafoods but risk being found responsible for the sockeye collapse, or they can try and defy the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Cohen Inquiry and World Health Organization for Animal Health, keep their secrets and be content with lower prices. The answer is simple, close the barn door.

There are Canadian businesses rising to the challenge, developing closed, land-based aquaculture offering jobs and leading technological development. They have been marginalized by government, possibly because they compete with the Norwegian industry, but they could be better managed.

If a thriving B.C. economy is the goal, the solution is simple:

- Order all fish feedlots out of the ocean, no more ill-conceived "fixes"

- Encourage wise development of Canadian land-based aquaculture to replace the jobs lost from closing ocean feedlots

- Allow us to use what we know about wild salmon to restore them to the benefit of BC and Canada

The only losers in this scenario are foreign shareholders, those taking B.C.'s rivers for private power generation, logging, mining, and oil companies who would put our coast in jeopardy from tanker traffic. In a world of failing food security, toxic oceans, and frail economies, wild salmon are far more precious to B.C. than any single industry.

Canada's mismanagement of the salmon feedlot industry is a building scandal on the world stage. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Food, Labour + Industry, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: