Biking 20 kilometres to and from her classes at Langara every day was the norm for Juliet in the months before she fell ill with COVID-19 in December.

Juliet was too sick to get a test for COVID when she got sick. Multiple close contacts later tested positive, but she couldn’t get out of bed, “let alone stand outside for hours with a bunch of sick people.” Her underlying lung issues made the illness even worse.

Now, nearly a month after her initial symptoms resolved, she has to take a break if she tries to walk three or four blocks. The fatigue and brain fog have been relentless, and lingering chest tightness sent her to the emergency room earlier this week where they gave her an inhaler to alleviate the pain.

“I literally caught this on the last day of finals and fell off the cliff,” said Juliet, who asked to use her first name due to privacy concerns. “I was supposed to be job hunting last month, not lying in bed.”

The East Vancouver mother of two is one of tens of thousands of British Columbians who have or will develop persistent COVID-19 illness, known as long COVID, during the Omicron wave.

But many — or most — won’t have proof of their initial illness because of extremely limited testing access and an overwhelmed system.

Advocates are concerned that without positive PCR test results, long COVID sufferers won’t have access to the already limited timely and targeted treatments, financial supports and other necessities to improve their quality of life.

One organization is saying people should be able to access B.C.’s four post-COVID recovery clinics without positive PCR tests because thousands of people are ill but ineligible for testing under the province’s current guidance. The clinics, all in the Lower Mainland, bring together specialists from all areas to provide co-ordinated, individualized care to people experiencing long COVID symptoms in B.C.

“It’s tough for a lot of people who don’t have those results in their hand that confirm they were sick with COVID-19,” said Jonah McGarva, a sound engineer who founded the advocacy group Long COVID Canada. “They’re not able to get the help that they’re needing.”

B.C. is currently testing about 15,000 people each day, but only those over 70 or working in high-risk settings like health and long-term care.

People have waited up to six hours in lines for testing centres in Metro Vancouver.

Independent modelling estimates that about 13,000 people are becoming infected with Omicron every day, about eight times more than is reported by the province daily.

Much is not yet known about long COVID, a post-viral syndrome that an estimated 10 to 30 per cent of people who recover from COVID-19 develop in the months after their initial illness. It affects both vaccinated and unvaccinated people of all ages, and can develop after asymptomatic or extremely mild cases too.

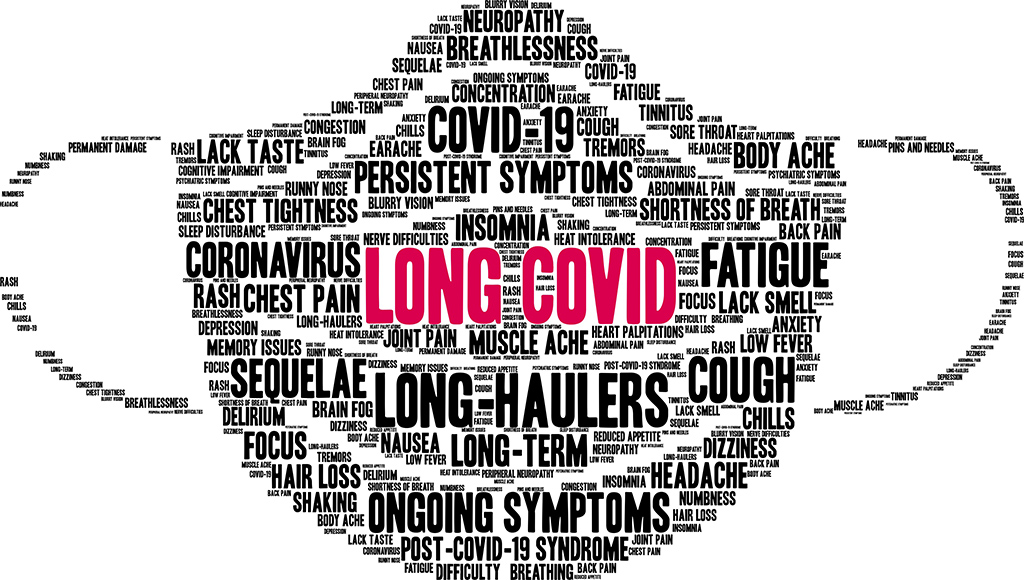

The symptoms are varied and include brain fog, muscle soreness, extreme fatigue and exhaustion, long-lasting loss of taste and smell, chest pain, shortness of breath and mental health effects like anxiety and depression. Many longhaulers report not being able to work or study, connect with friends and family or do many things like exercise.

Conservative estimates say up to 150,000 people in Canada have long COVID. McGarva says a lack of awareness of the syndrome among health-care providers and the public means many more are likely impacted but don’t recognize their symptoms as a result of COVID-19 infection.

“It’s creating a mass-disabling event of epic proportions,” said McGarva.

McGarva became ill with COVID-19 in March 2020, before testing was scaled up or available to the public. It took 18 months and three doctors until his referral to the post-COVID clinic in Abbotsford was accepted, which he credits to the persistence of his physician and his own advocacy work.

But many others who couldn’t access testing or never got a confirmed positive result in the early days of the pandemic are nearing two years without supports despite debilitating illness after their infection.

Elle Read, who lives in Kelowna, had suspected COVID-19 in March 2020 and took a single PCR test which came back negative. While PCRs are the “gold standard” for tests, they still don’t detect all infections at every stage.

The 37-year-old then developed more severe symptoms and a “textbook case” of long COVID. She was denied further PCR tests and her referral to a post-COVID clinic was recently denied because she did not have a positive test result.

But after her acute illness was over, she developed many concerning symptoms, ranging from tremors in her legs and body to memory and cognitive function loss and extreme fatigue.

Read said she was brushed off and dismissed by many doctors when she described her symptoms. As someone who also has myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome, she has had doctors refuse to treat her and suggest that long-term symptoms from viral infections are not likely.

“With the new restrictive testing guidelines unrolled this week in B.C., I worry others will be denied referrals to the long COVID clinics or even care from their doctors and future specialists, when they don’t have a positive PCR test history,” Read wrote in a message to The Tyee.

“Even with all the evidence, receiving care and acknowledgement for post-viral illnesses in B.C. is an uphill battle.”

B.C.’s post-COVID recovery clinics have always required a positive PCR test result for referrals for the sake of easy administration and ensuring the research that comes out of the clinic is based on patients recovering from COVID-19, explained clinic lung specialist Dr. Chris Carlsten.

“I’m very aware of the issues that poses, and as a group we’re very cognizant of the fact that we need to do better in terms of those that may have had COVID and long-term sickness and may not have had a test,” said Carlsten in an interview.

The challenge, Carlsten said, is broadening the diagnosis criteria beyond a positive PCR test while also ensuring people aren’t misdiagnosed with long COVID and go untreated for other chronic conditions missed. That’s made even more difficult by the syndrome’s very non-specific and diverse symptoms.

“But that challenge shouldn’t dissuade us, because what COVID’s done is show the reality of a debilitating post-viral syndrome,” he added, noting the clinic’s long and growing waitlist. “We can’t turn away from this challenge.”

McGarva stressed that the research challenges shouldn’t be answered at the expense of a community of people who have had to fight for very basic recognition.

“The PCR requirement creates stigma and further ableism and discrimination on our communities,” he said. The requirement for a positive test extends to things like disability, welfare benefits and employer accommodations for ill workers, he added.

Canada is already “so far behind the eight-ball” in terms of recognizing the detrimental impacts of long COVID and the need to support sufferers, McGarva added.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has advised a PCR test positive result is not needed to diagnose or treat long COVID. In other jurisdictions like the United Kingdom, guidelines on diagnosing long COVID have been released that include several other indicators, like blood oxygen depletion, alongside PCR test results.

McGarva hopes that Canada and British Columbia will catch up as Omicron magnifies the scale of support that many survivors will need.

Juliet, who has already experienced some relief from her inhaler, is still nervous about what not having a test result will mean for her as she applies for jobs and requests accommodations in the future. Her oldest child, who is 26 and has developmental disabilities, also relies on her for many necessities.

She did not qualify for any COVID-19 income supports because she was in school when she fell ill so didn’t technically lose income. Juliet is living off her small savings from scholarships and light part-time work and hoping she can get a referral to the post-COVID recovery clinic if her symptoms persist.

Juliet still wishes there had been a way for her to get a test in December, and that the system hadn’t been overwhelmed.

As she starts to apply for work in the future, a PCR test result would allow her “to be taken seriously as I am actually unwell and it’s not just that I’m lazy and out of shape.”

She’s seen her son’s diagnosis with autism help him gain access to needed supports, and worries about her future grappling with long COVID.

“I don’t know where this is going to go from here.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: