The letter was just four lines, and the second one stunned Alli Anderson. It said her father was dead.

“Regretfully, I have been informed that Francis Jordan recently passed away and I would like to express my condolences,” wrote a consultant at the Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia.

Francis Patrick Jordan had in fact died a week earlier, on July 1, while in Peace Arch Hospital in White Rock, B.C., but this was the first Anderson and her mother Margaret Jordan knew about it, because they were never told by the hospital.

Now Anderson was staring “in shock and disbelief” at a business letter addressed to her mother. It said the trustee who had been referred to help Francis Jordan manage his financial and legal affairs was closing the file.

Shock then turned to frustration for Francis Jordan’s family. Over the next week they tried to figure out what had happened and give Jordan a proper burial, but said they were “iced-out” and made to feel like they had no right to act on his behalf and make arrangements.

They were caught up in a bureaucratic journey that reveals challenges families with complicated dynamics face when dealing with the health system.

And there are questions about a possible added layer. Francis Jordan was not Indigenous, but Alli and Margaret, who are, wonder if systemic racism played a role in denying them access to information.

It would take days of calls and an in-person visit to the hospital to get any answers. During that agonizing effort, the body of Francis Jordan, whose family called him Pat, would lie in the morgue for 15 days.

Out of the loop

Alli Anderson and her mother had been estranged from Francis Jordan for about eight years, though as far as they knew Margaret remained executor to his will.

In April, they learned from their family doctor that Jordan had been admitted to Peace Arch after suffering a stroke. Anderson said she and her mother spoke with a hospital social worker in acute care about her father and explained their family’s complicated relations. As far as Anderson was concerned, that placed her in the loop regarding her father’s condition.

In May, she says, she called the hospital operator and learned her father had been moved from acute care to the Dr. Al Hogg Pavilion for long-term care — the last she would hear from the hospital while Francis Jordan was alive.

After Anderson read the letter to her mother mentioning her father was dead, she started seeking answers.

She called the Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia and social workers at Peace Arch, but says no one could tell her much.

Anderson said she eventually got a call from a nurse who worked on the floor where her dad had been treated, who said Jordan had started to deteriorate on July 1 and likely died after another stroke.

The nurse also told Anderson that her father’s body was still in the morgue after eight days.

“It’s absolutely disgusting to do that to anybody, despite the circumstances or familial relationships,” said Anderson.

Why wasn’t Anderson or her mother contacted to make funeral arrangements?

A social worker team lead eventually called her back to say that her father had provided the hospital contact information for only one family member, who had been informed of his death. Hospital protocol was followed — even if protocol apparently failed to sound an alarm that no one was stepping up to claim Jordan’s body.

The family member the hospital contacted was a person Anderson and Jordan hadn’t spoken with in years and say they have no way of contacting.

And somehow, even though legally Margaret Jordan had the right and responsibility to make any decisions about Francis Jordan’s final arrangements as the executrix in his will, she was left in the dark.

How long would Francis Jordan’s body have remained in the morgue had Anderson not continued to question the hospital? What would have become of his remains?

Those troubling questions remain unanswered for Anderson and her mother. In fact, in their first efforts to reach out to the hospital for guidance, they were not told they could access the body and weren’t given any information on what to do next, they say.

“We feel like our closure was stolen,” said Anderson. “I’m just absolutely frustrated; completely. There’s nowhere to go. No answers, no one will talk.”

‘We could not believe we were excluded’

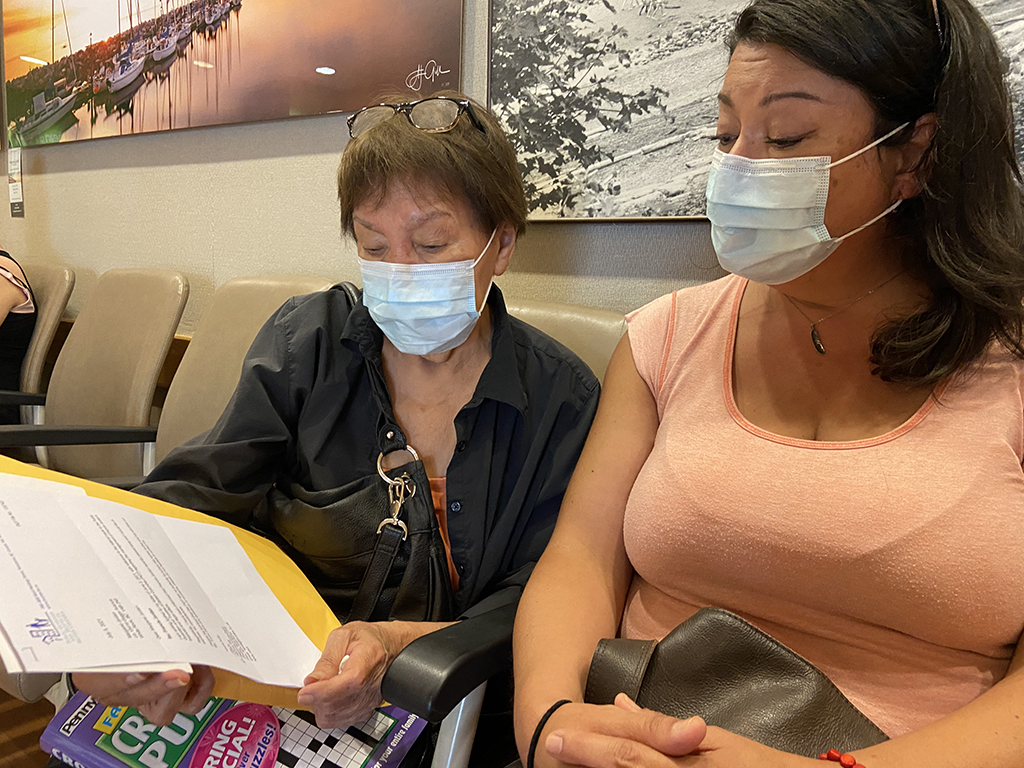

Finally mother and daughter, who both live in White Rock, decided to go in person to Peace Arch hospital on July 12, nearly two weeks after Jordan’s death.

Margaret Jordan arrived at the main entrance armed with an envelope full of documents, including Francis Jordan’s will that named her as the executrix — and a big crossword book to pass time during the long waits she anticipated.

As they spoke with receptionists, a registrar and social workers, they pieced together that Anderson’s contact information might not have been shared between units after Jordan was transferred from acute care to long-term care. They also confirmed that Margaret Jordan had the right to start making final arrangements.

Margaret Jordan, who is Inupiat, and Alli Anderson, who is Inupiat and Scottish, also can’t help but wonder if their Indigeneity played a role in how they were treated.

“Being Indigenous in Canada is not easy, especially in the health-care system,” said Anderson. “As an Indigenous person, one can’t help but think, ‘Did this play a part in this situation?’ You can’t help but ask, ‘Would this happen to a Caucasian Canadian?’”

There is widespread Indigenous-specific discrimination, racism and stereotyping in B.C.’s health-care system, as laid out in Dr. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond’s 2020 report, In Plain Sight.

The report, launched by the B.C. Ministry of Health, found that some of the most common discriminatory behaviours were long wait times, denials of service, lack of communication or failure to provide appropriate information.

“That is every single box ticked in this situation,” said Anderson, who noted her mother spoke with an accent.

Thinking about those interactions now, they both wonder if subconscious, systemic racism contributed to delays in getting information. “A lot of the times, I think they don’t realize that this is related to hidden prejudice. It’s subconscious until they’re made conscious of it.”

Anderson has filed a complaint with Fraser Health’s Patient Care Quality Office.

Fraser Health wasn’t available for an interview. In an email statement, a spokesperson said the authority is looking into the family’s concerns and will “determine whether there is an opportunity to modify our process moving forward to meet the needs of each family.”

The email said generally the next of kin who is responsible for patient care is the one notified if that patient dies, and then it is up to that person to update other family members and work with the facility on further arrangements. In this case, Fraser Health says staff followed their current process around a death notification.

What is that process, and where can it fray? In a hospital, a patient’s listed contact for health decisions is not necessarily the same contact who is responsible for final arrangements if that person dies, said founder and owner of KORU Cremation, Burial and Ceremony, Ngaio Davis.

“It can cause a bit of confusion,” she said. As a funeral director, part of her role is to communicate with the hospital about when the deceased person can be moved from the hospital morgue and complete the registration of death.

The person who has the right to start making final arrangements is determined by B.C.’s Cremation, Interment and Funeral Service Act. If there is a will that names an executor or executrix, then that person has the right to move the deceased from wherever they’ve died and give permission for the disposition, said Davis.

If there is no will and that person is an adult, the next person responsible is the deceased person’s spouse, adult children, adult grandchildren, parents, adult siblings then adult nieces and nephews. If there is no one, then the Public Guardian and Trustee of B.C. could take over.

Normally, if a death isn’t suspicious, it doesn’t take more than a few days to move someone’s body from the hospital morgue to a funeral home.

“As funeral providers, we have to go down that list to make sure that we’re working with the correct person,” said Davis. Any health-care facility is also obligated to follow the same section of the law, and most of the time that happens, said Davis.

But there can be some tense situations, “where the person the hospital has listed as the point of contact is not the person obligated to take control of things after the death.” (See sidebar for more family resources.)

In the Jordan family’s case, those two people were estranged and not in communication. Anderson said she doesn’t have a way to contact the person listed as her father’s health contact.

The Tyee has seen a will for Francis Jordan dated 2014 that lists Margaret Jordan as the executrix.

Navigating complicated family dynamics happens quite often, said Davis. Still, the law makes it very clear about who should be responsible for someone’s body after they die. And that was Margaret Jordan, assuming the will has not been changed.

“Although we are estranged, it’s a horrible thing when a parent passes, or when a husband passes,” Anderson said. “My mum was married to him for over 50 years and is the sole executor in his will. We just could not believe we were excluded.”

‘So many hoops’

The labyrinth that prevented Margaret Jordan from knowing about Francis’s death and following through on her duty to take care of his remains is an example of what Davis sees as a bigger systemic issue. “The death-care system isn’t really in sync with the health-care system. Like they’re two completely different systems. And there should be some overlap.”

With more overlap, perhaps someone at Peace Arch would have noted that Francis Jordan’s body remained unclaimed in the morgue for over a week, and retraced some conversations with Alli Anderson and Margaret Jordan and let them know.

Davis sees room for more conversations and education around what happens after someone dies. She suggests that there be someone on staff at every hospital who has a basic understanding of death care and could provide resources to family members. “They just need to know: here are the laws now that somebody died, and they could be quite different from what they’re guided by when someone’s alive.”

As Jordan and Anderson were wrapping up their last conversation with a social worker at Peace Arch Hospital on July 12, they shared that Jordan is a residential school survivor. Jordan said the confirmation of hundreds of unmarked graves on the grounds of these so-called schools has been heavy in her mind and heart. At the end of a long afternoon of trying to find her husband’s body, she teared up as she shared a quote that had been on her mind: “The children are saying they have finally found us.”

After leaving the hospital, the family was able to contact a crematorium and make final arrangements. They now have the ashes of Francis Jordan — but only after his body lay in the morgue for over two weeks.

“It was closure that should have come sooner and without so many painful hurdles and hoops to jump through,” said Anderson. “For it to end so bitterly is tragic.”

She and her mother hope that the hospital will take a fresh look at how members communicate with family members of the deceased. They hope a new process goes beyond a checkbox list of to-dos, and that there are resources for anyone with questions about what happens next.

Said Margaret Jordan: “I don’t want that ever to happen again to someone else.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: