Illicit drugs are usually bought in the shadows, and then often consumed alone. But as Canada’s black market drug supply has become increasingly tainted with unstable mixes of fentanyl and benzodiazepines, both are increasingly deadly activities.

Activists gathered Wednesday in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood to show how bringing drug use into the light could help save lives.

The protest came as British Columbia entered its fifth year of a public health emergency because of rising deaths due to poisoned drugs. The group, the Drug User Liberation Front, staged a similar event last year.

At Dunlevy and Hastings streets, members of the Drug User Liberation Front set up a table and gave out heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine in small cardboard boxes. The boxes were clearly labelled with what was in the drugs and at what percentage — for instance, 40 per cent heroin, 60 per cent caffeine.

The group said the drugs had been tested before distribution and did not contain “fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, benzodiazepines and many other harmful cuts, buffs or adulterants.”

Mary, a Downtown Eastside resident who picked up a box of heroin, said she had overdosed several times. She marvelled at the small box in her hand, with its label showing what exactly she would be taking. “We don’t do heroin — it’s fentanyl down here, or whatever somebody makes us in a bathtub,” she said.

Mary has tried prescribed safe supply in the past, but it hadn’t worked for her because her doctor was not allowed to increase the dose of her prescribed opioid.

Scott Joinson said he’d never had unadulterated cocaine, and he wanted to know what it was like. He said he had overdosed several times.

“If it was done with government backing, then we would know what’s in our drugs. If it was sold in stores, people would know as consenting adults,” he said. “Take a look at what’s going on — the black market is forcing us to take adulterants, which is killing us.”

Eris Nyx, one of the organizers of the event, said the drug handout was limited to people over 18 who already use illicit drugs. The group bought the clean drugs on the internet using cryptocurrency, she said.

She said the event was modelled like a compassion club and showed that the model could work to supply people who use drugs with safe products.

“Anyone can reproduce this model,” Nyx said. “It is a model that could be expanded immediately by drug users all over the country, if the government was ready to regulate it.”

Drug-testing services and Overdose Prevention Society staff were present at the event.

Dr. Mark Tyndall, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health, said he supports the demonstration.

The only way that supports for drug users seem to happen is when they take action, he said.

“Somebody said at the rally last year, ‘Nobody’s coming to save us,’” Tyndall said. “I think these are sort of important demonstrations, going against regulations and just showing what can be done.”

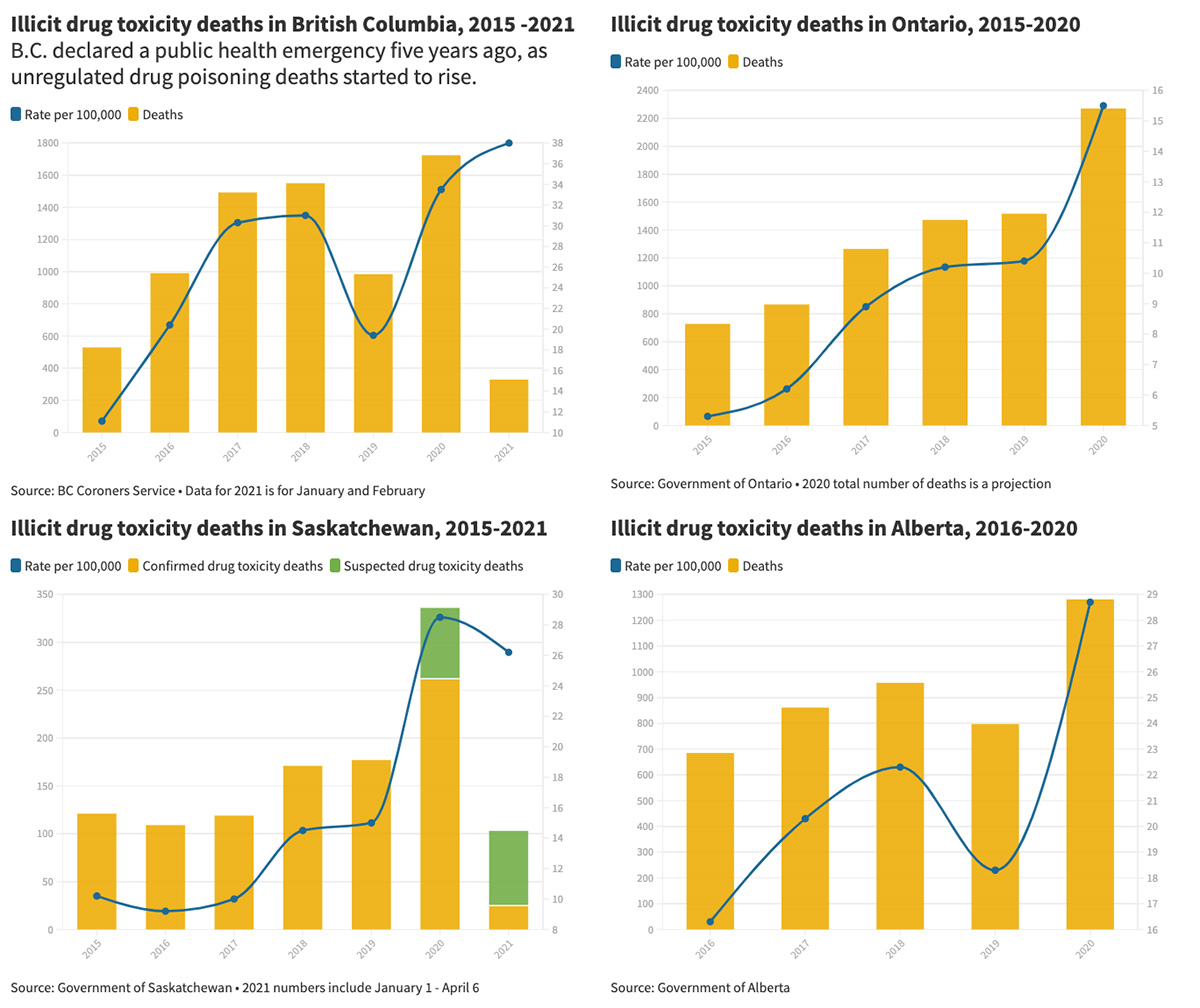

In 2016, community activists set up overdose prevention sites, which were technically illegal at the time. Faced with soaring death rates because of the increased use of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, the provincial government quickly moved to approve the model.

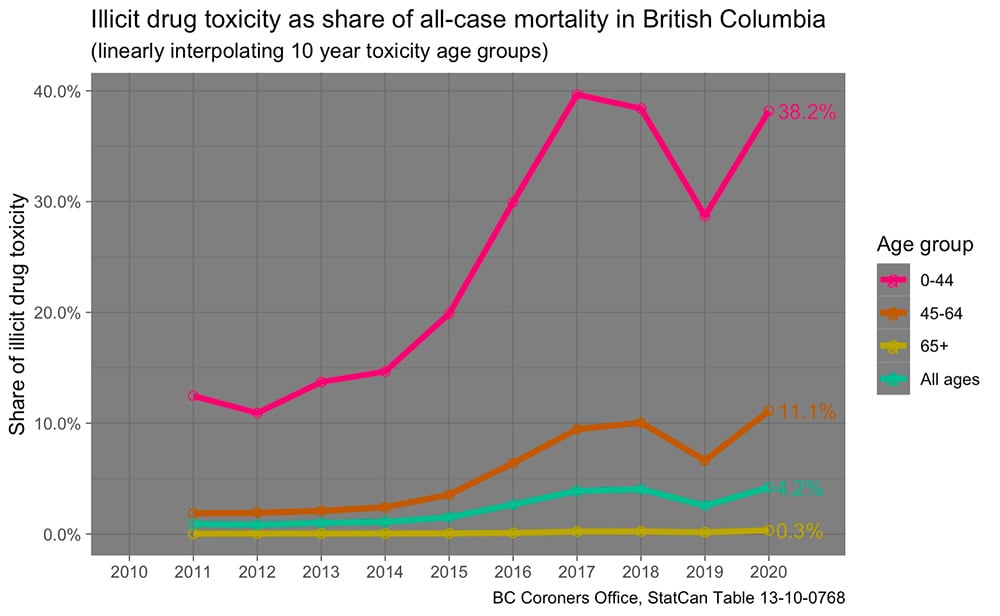

Death rates finally began to fall in 2019. But all that progress was erased in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic brought more toxic drugs onto the streets, and more people used drugs alone as community connections were severed.

In B.C., just over one-third of all deaths of people under the age of 44 last year were caused by poisoned drugs. The province had the highest number of deaths ever recorded from illicit drug toxicity in 2020 and is on track to continue that trend. Other Canadian provinces have seen a similar increase.

While the provincial health officer created new public health orders to expand access to safe supply, advocates in B.C. have been frustrated by delays to the rollout and ongoing barriers.

Tyndall said many doctors are still reluctant to prescribe prescription opioids. Just a few years ago, regulators were scrutinizing doctors who over-prescribed opioids to patients. There is skepticism that safe supply is the right treatment for people who are addicted to illicit drugs, as well as liability fears.

“Although there are guidelines now, they’re just guidelines,” Tyndall said.

“Physicians are still concerned that somebody they’re prescribing to will have an overdose and they’ll have the prescribed drugs in their system. They may very, very likely have other drugs in their system too. But there is quite a liability that physicians feel by doing this.”

Tyndall, who created a vending machine system called MySafe that dispenses opioids, said safe supply needs to be seen as a harm reduction public health measure, not something that necessarily needs to be overseen by a doctor.

“When we medicalize these things, the expectation is this is a stepping-stone to addiction care and treatment and detox and people want to make this a comprehensive kind of care package,” he said. “Many people aren’t ready for that or have failed that many times.”

Dr. Andrea Sereda, a physician in London, Ont. started prescribing the prescription opioid Dilaudid in 2016 and now treats 300 patients. She said doctors in Ontario face similar barriers, but the idea has become more accepted over several years.

“We’re different from B.C. as well in that all safe supply programs are pretty rigorously embedded in primary care,” Sereda said.

Sereda said other doctors have come on board after she presented data “showing that we were keeping people alive, we were preventing a lot of infectious complications related to injection drug use of our clean supply,” as well as preventing HIV and controlling existing infections.

Tyndall and Sereda said there needs to be a wider range of prescription alternatives provided to people. For instance, in Ontario Sereda can’t prescribe liquid hydromorphone at the concentration that patients who have developed a very high tolerance would need. She’d also like to see heroin and more fentanyl products made available to prescribe.

Activists at the Downtown Eastside rally called for fentanyl and benzodiazepines to be added to safe supply. (Benzodiazepines are a depressant increasingly added to illicit opioids and stimulants and that can cause dangerous blackouts and breathing problems.)

For political reasons, Tyndall said it’s trickier to advocate for a safe supply of stimulants and benzos. But he doesn’t disagree with the call to provide safe and regulated drugs of all types as an alternative to the current dangerous, unpredictable supply that is controlled by organized crime.

“So many people are dying of too many opioids and contaminated products and especially fentanyl,” he said. “So I think that needs to be our main focus, but I do think a lot of the activist community may not even use opioids, they use other substances. Why should they be buying mystery drugs when we should be regulating them all?”

In other parts of Canada, safe supply to prevent drug poisoning deaths isn’t yet part of the mainstream conversation, Tyndall said.

In many provinces, setting up overdose prevention sites is still an uphill battle, even as death rates soar.

In Saskatchewan, the government refuses to fund the only overdose prevention site in the province, located in Saskatoon. In August, the Alberta government cut funding to a site that had operated in Lethbridge and had been the busiest site in the country.

For those politicians who are reluctant to fund or allow safe drug consumption sites, safe supply could actually be a more politically palatable alternative, Tyndall said.

“Part of my epiphany about all this is spending time at overdose prevention sites and just watching a parade of people overdose every day,” he said.

“The same people bring in the same stuff and overdose, and all we can offer them is naloxone and oxygen and work to save their lives, when we could be offering them drugs that they would use that won’t kill them.

“Maybe these places that are still stuck on supervised injection sites could just open up clinics where you can give people a safe supply of drugs.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: