Someone knew laughter and joy in the past,

Someone knew sorrow, suffered and cried,

Memories now sadly locked away fast —

Someone’s a person still, deep down inside.

— From Paul Gregory Leroux’s poem “Someone”

In 2010, Paul Gregory Leroux started tripping and falling. Two years later, he was diagnosed with the debilitating disease inclusion body myositis. The neurologist told Leroux to expect losing the use of his arms and legs over the next 20 years. The deterioration happened sooner; by September 2017, he could no longer walk and was confined to a wheelchair.

A year later, as his neck muscles weakened, Leroux suffered two significant choking episodes that required use of the Heimlich maneuver. In December 2017, when he moved to Extendicare Medex, a long-term care facility in Ottawa, he was among the youngest there at 59. Most of the residents were 80 or older.

He was an unusual resident for another reason as well — he was an out gay man.

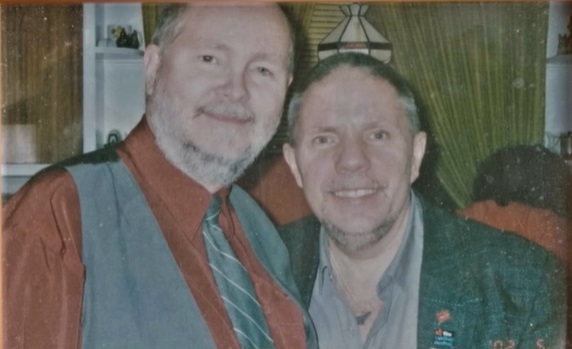

And that is how, last year, I came to meet Paul Gregory Leroux. I was working on Forget Me Not, a documentary for Vancouver-based OUTtv about how generations within Ottawa’s LGBTQ2S+ community relate to each other, and how younger members think about their predecessors’ sacrifices and activism.

Finding elder members of that community living in a retirement or nursing home proved to be a challenge, and not only because of the lockdowns associated with the pandemic.

I had been warned by veteran members of the LGBTQ+ community that few in those living arrangements for the elderly would be willing to appear on camera, because they typically re-closet themselves for fear of homophobia among other residents.

But Leroux had from the beginning been out and proud at Extendicare Medex, openly kissing his husband and life partner Alex Wisniowski when he came to visit. (No one seemed to bat an eye, by the way.)

I asked Wisniowski if he and Leroux would be part of the documentary, and over the past many months our relationship moved beyond journalist and subject.

Now Leroux’s condition has taken a sharp turn for the worse. He has very little time to live and knows it. Our friendship has grown as he has shared this thoughts and writings with me. In such revelations, he offers a glimpse of one inner life among thousands hidden from public view and facing mortality in Canada’s long-term care facilities.

“I feel myself drawing away from everything. I don’t know what awaits me beyond this life. My world has become smaller and smaller,” he said in a final testament of sorts that I recorded for him on video in my most recent visit earlier this month. “I hope that I’ve achieved some good in my lifetime.”

“When I was young, I wanted to be famous or have a following. And my reach has not been very extensive in my influence. I don’t know whether I will be remembered by many people for very long.”

I felt overwhelmed by the privilege of bearing witness, as well as the difficulty of focusing my camera — and breathing — while wearing a mask and face shield. Our visit stretched on, lasting nearly three hours.

I was wearing a hoodie under my hospital gown. “You look like a monk,” said Leroux, a fellow Catholic, who told me that he once considered the monastic life. I replied that when I was 17, I did too — very briefly — at a Long Island novitiate, but the lure of the bright lights of nearby Broadway ended that after a week. Leroux laughed.

He asked me to take his personal writings and see what I could do with them. They include this poem he entitled “The Sea and the Shell.”

When you look

With your eyes

You see only the shell

Of the person I used to be

Empty, hollow

Cast away

On the far shore

Of Life

But if you hold me close

And listen

With your soul

You will hear

The roar of the ocean

That echoes yet

Within me

The person I am still

Deep inside.

Born in Montreal, Leroux worked as a translator for the federal government. I learned about him via a 2018 Ottawa Citizen story that explained Extendicare Medex had held its first Pride Week celebration thanks to Leroux’s efforts.

He came out as gay five years after the 1969 Stonewall riots, and openly and from that day on uncompromisingly embraced his sexual orientation.

At the celebration, there was rainbow-coloured Jell-O, a Pride cake and Leroux sang, a cappella, a selection of songs, including “I Am What I Am” from La Cage Aux Folles, and Frank Sinatra’s signature “My Way,” written by Ottawa native Paul Anka. Leroux dedicated “Endless Love” to Wisniowski, which became their “theme song” after dancing to it on one of their first dates in 1981.

They married in 2005.

Leroux is grateful they have each other. Many Extendicare Medex residents are single, have lost a spouse or have been abandoned by family.

Nevertheless, staying connected has not been easy for the couple. Wisniowski faces a 90-minute commute one way — through a combination of buses and light-rail — to travel from the east-end, one-bedroom apartment he and Leroux had shared for 35 years. Wisniowski serves as the building’s manager.

The pandemic has also affected the way the couple interacts. For seven months last year, long before they received their vaccines this year, the couple could not kiss or even hold hands when COVID-19 was running rampant through long-term care facilities across Canada. During the five outbreaks that hit the home between March and December, Leroux was confined to his room and Wisniowski had to don full personal protective equipment while physically distancing from his spouse.

Leroux, who never contracted COVID-19, made the most of his alone time, writing poetry, short stories and an opinion piece for the Citizen during a two-week period in isolation last July. “While always introspective by nature, I did not turn inward upon myself,” he wrote. “Through my open door, I watched and listened to others out in the hall. I felt the pain of fellow residents who were having a harder time adjusting to our new circumstances.”

“I was sorry I couldn’t do anything to help them.”

In an interview for the documentary, he reflected on how the three years he spent in long-term care has broadened his outlook on life.

“I am not so focused on my own needs,” said Leroux. He explained his shift was one from “diversity” to “commonality — what we share as human beings aging together.”

In the op-ed he wrote for the Citizen, Leroux described how, for him, long-term care “became an uplifting experience. Little did I know that my best days lay, not behind, but ahead of me.… I was about to embark on an incredible journey of personal growth and spiritual rebirth.”

He described witnessing “tender moments between spouses, happy occasions uniting families,” and feeling that his relationship with Wisniowski had grown “deeper and stronger.”

“I have learned the importance of common courtesy, simple human decency, kindness, gentleness. It takes so little to make others feel they matter: greeting people by name, expressing gratitude, welcoming, listening. Lending an ear, a hand, a shoulder, creates a bond of trust and can open the door to the sharing of confidences.”

The power of advocacy that Leroux learned living through the rise of the LGBTQ+ movement and the AIDS epidemic, he has applied within the walls of his care facility. “But now I use it not so much for myself as to advocate for others,” he told me. He and Wisniowski established a family council at Medex. Leroux notes, “It’s ironic that it took two gay men to do that.”

He hasn’t played favourites in who he seeks to help or make allies. “In a world where people are polarized and choose camps, and are not able to see another point of view, I’ve tried to see both sides of the coin,” he told me during that early-March visit. “I have friends at completely opposite ends of the political spectrum.”

When I last visited Leroux, I could see he’d lost a lot of weight. Given his difficulties swallowing, he was living on Mr. Freeze pops and whatever liquid he could take down.

On a table, next to his hearing aids and eyepatch, lay his two favourite books: the Bible (“one of the foundational texts of western civilization,” in his opinion) and The Forsyte Saga, written in the 1920s by English author John Galsworthy about a British upper-middle-class family. Leroux discovered the series of three novels and two other short fictions, which lay bare the emptiness of materialistic morals, when he was 10 years old. He has reread it many times not only in the original English, but in the French and Italian translations.

Leroux's humanity and resilience reminded me of my father, who, as I have recounted in these pages, died in an Ottawa hospital two years ago. Despite enduring pain, suffering, discomfort, disorientation, separation anxiety, loneliness and neglect through the health-care system, my dad always had a kind word for a nurse. But at the end, he was not able to share the kinds of reflections offered to me by Leroux, because by then my father was in the full throes of dementia. At times he would shout out, the result of confusion or exasperation at being left strapped into a chair alone in his hospital room.

My pa was like a lot of people Leroux lives with and advocates for now. Leroux reminds me that many in the facility are “unable to express themselves. And yet you can tell that there’s a human being in there.”

In the blue binder full of writings Leroux gave me is a poem he wrote in December 2017, the month he moved to Extendicare Medex, called “Dreaming My Way Home,” which includes these words.

In dreams at night, unaided, on two feet,

I find my way back home, walk up the street,

Without a cane, a walker, or a chair,

Open the door, see my beloved there.

While being filmed for Forget Me Not last October, Leroux said that he dreams a lot. And in those dreams, like too many of his waking hours, he is separated from Wisniowski. “I’m trying to find my way home,” Leroux said, as he choked back tears. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Coronavirus, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: