If Lisa Wagner had known having her son learn from home this school year meant the Grade 7 student would only be graded on one-third of the subjects he studied, she would’ve made a different decision.

“There was never any time that I recall being told that if you have a child in Option 4, that your child will only learn one-third the subjects that a child would learn if they were in class,” she said.

Unique to the Vancouver school district, “Option 4” was a last-minute addition to the district’s back-to-school plan last fall.

When the plan was unveiled in August, students had three enrolment options for the 2020–21 school year: in-class instruction; online distance learning through the Vancouver Learning Network program; or withdrawing from the district altogether to be home schooled.

But choosing distance learning or home schooling meant students would give up their spot at school and might have to transfer when they return to class. Many families had joined lotteries or sat on long waitlists to get their children into the school of their choice.

For families like the Wagners, who were unable to send their kids back to school for health reasons, it felt like they were being punished for prioritizing their health in a pandemic.

Just days before schools reopened last fall, Option 4 was introduced as a temporary solution for students in kindergarten to Grade 7 to learn from home without losing their seat at school.

A teacher would check in on students weekly, but parents and guardians would be ultimately responsible for their children’s education.

The expectation from the district was that families selecting Option 4 would gradually return to in-class learning. Originally intended to run for one month, the program has been extended many times: to the end of December, then the end of March, and most recently to the end of this school year.

The district has yet to make a decision on whether Option 4 will be available next year. The number of students choosing the approach has dwindled to just over 1,800 students, down from more than 4,000 in September.

But when mid-year report cards came out at the end of January, many Option 4 families were caught off guard.

Wagner’s son, who is taking Grade 8 math and hopes to get into one of Vancouver’s mini school enrichment programs next fall, received a report card assessing him on only three of his nine subjects. And the grades he did receive were much lower than normal.

“My son literally brought the report card home in tears,” Wagner said, adding the family is embarrassed to send the report card to the mini schools he is applying for. Mini schools consider Grade 6 and 7 report cards, among other criteria, when evaluating applications.

“I don’t feel that any child who is staying home because their family thinks that that’s the safest thing to do should be penalized educationally for making a choice that was offered by the school board.”

The issue, says Jody Polukoshko of the Vancouver Elementary School Teachers’ Association, is that the school district created a new way of learning with Option 4 but didn’t hire more teachers or provide new learning resources.

“What happens in report cards, that’s a byproduct, not the problem, in my view,” Polukoshko said, adding she understands parents’ frustration and disappointment around report cards.

“There’s a systemic problem with the way that Option 4 is being provided. And that comes down to lack of equity, provision of service and of responsiveness from the district.”

‘Insufficient evidence of learning’

The Tyee spoke with four families upset with their childrens’ Option 4 midterm report cards. Each experience was slightly different.

Claude Martins' eldest child, Cate, in Grade 6, has the same concerns as Wagner’s child about getting into a mini school after her midterm report card only evaluated her in one subject, English language arts.

“Cate has done math assignments every week since the beginning. The line in the mathematics section is just that boilerplate ‘Due to participation in Option 4, no proficiency scale indication at this time,’” Martins said.

“And I feel like if someone just looked at that at a glance, they may get the impression that she did no math work across the whole school year, which is not the case.”

Kieran and Shufen Tether were already having issues with Option 4 before they received their six-year-old’s midterm report card.

Despite Option 4 promising 1.5 to 2 hours of weekly check-ins with a teacher, the Tethers would get at most 30 minutes. The work they submitted to the teacher was never assessed, either, they said.

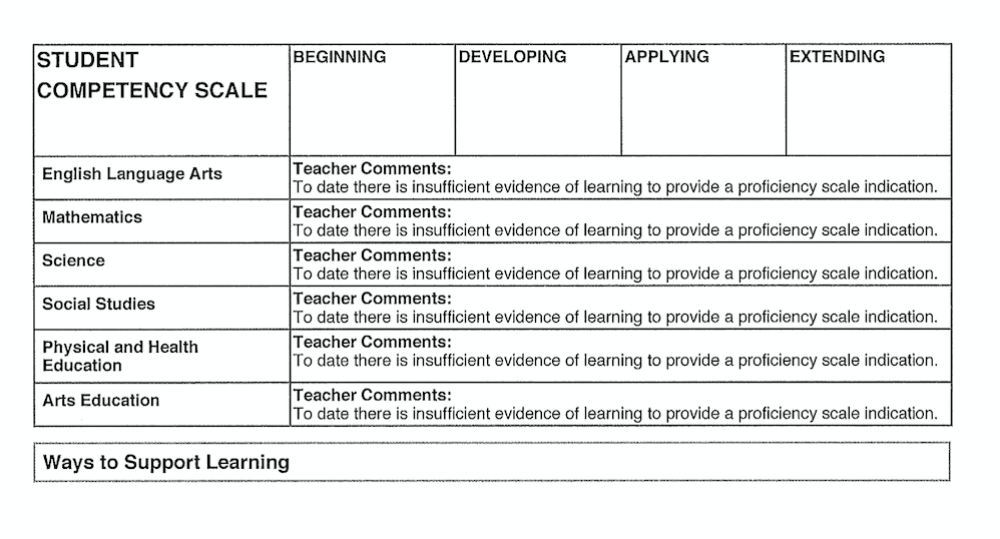

When their child’s report card came home, it only said: “To date there is insufficient evidence of learning to provide a proficiency scale indication.”

Yet their friend’s child, who had transitioned back to in-class learning from Option 4 a week before report cards came out, received a full assessment based on work completed at home.

“It feels like there was no thought put into what would happen to anybody that stayed at home,” Kieran Tether said.

After complaining to the teacher and principal, the Tethers will receive a new midterm report card. But they have decided to transition their child into the online Vancouver Learning Network for the rest of this school year and for next year.

Chris Raedcher’s children have had very different experiences with Option 4, despite attending the same school.

One teacher is going above and beyond in terms of reaching out and assigning work, “sometimes after school hours,” Raedcher said, while the other has spent far less time with their child and didn’t provide assignments.

The Vancouver School Board’s website says while parents are ultimately responsible for ensuring their kids do their school work in Option 4, a teacher is supposed to provide assignments and monitor students’ progress.

While one of Raedcher’s children received a report card that assessed them in everything but physical education and social studies, the other was only assessed in math and language arts.

After complaining to the teacher and school administration, communication from the latter teacher improved. But that doesn’t solve Raedcher’s overall issue with Option 4.

“I would like to see somebody say, ‘This is what we should expect.’ So that there’s a standard that everybody is aware of, because that is just not clear,” he said.

Option 4 ‘essential,’ but lots of barriers

Teachers are in favour of Option 4, said Polukoshko of the Vancouver Elementary School Teachers Association, calling it “essential” during a pandemic.

But they are not in favour of the expectation that classroom teachers will monitor both their students in class and in Option 4.

No additional resources have been made available for additional resources or teaching staff. However, a motion to use $3 million in unspent federal COVID-19 grants on Option 4 is winding its way through the board.

Introduced by trustee Barb Parrott at the Feb. 25 board meeting, the motion was referred to the district’s personnel committee, which doesn’t meet again until April 7.

The Vancouver Elementary School Teachers Association also doesn’t like the fact there has never been a long-term plan for Option 4 learners beyond hoping they would transition back into the classroom, Polukoshko said.

“When the program was extended to December, we raised really serious concerns and said, ‘What is reporting going to look like? What does instruction look like? How are we getting additional services, like counsellors, learning assistants or teacher psychologists to these students?’” she said.

“And there was just no movement from the district about doing things differently.”

Some schools, like the one the Tether’s child attended until recently, have seconded a resource teacher to monitor and interact with all the students in Option 4.

But resource teachers, who include teacher librarians, English Language Learner teachers and special needs teachers, have responsibilities to other students in the school. If they’re working with Option 4 students, Polukoshko said, that means there are students who are missing out on their services.

Due to an ongoing shortage of teachers on call, resource teachers are often pulled away from their jobs to fill in for another teacher who is out sick.

No matter who is assessing the student, it isn’t possible or even ethical to assess students in Option 4 the same way students are assessed in class, Polukoshko said. For one thing, not every student in Option 4 is meeting with their teacher or completing assignments.

“Teachers, also, when they receive a piece of work, they don’t know how much of that was done independently by the students,” Polukoshko said.

“If the students misunderstood the criteria, they’re not going to penalize students for that, because they’re obviously working independently.”

Report cards, which students receive at the end of January and again in June, are not the only forms of student assessment. Any communication from the teacher to the parents or marked assignment is considered an assessment.

“Sometimes there is a focus on report cards as being the key piece, but it’s one part of a bigger picture,” Polukoshko said.

The Education Ministry, which is responsible for student assessment requirements, should have cancelled report cards for students in Option 4, she added.

“The district and the ministry should have had a longer view on this piece. And could have anticipated many of these problems.”

The Tyee requested an interview with Vancouver school board chair Carmen Cho or Deena Kotak-Buckley, one of the district’s directors of instruction, but neither were made available.

But an emailed statement from a district communications person echoed Polukoshko’s point about the mid-year report card being just one of several forms of assessment students receive.

“The mid-year written report is not summative and is not required provincially. It is used locally only and is not entered into the MyEd provincial student information system,” the statement read, adding that any families with concerns about their report card should talk to the teacher.

“It is to be viewed as one of many communications of learning shared with parents to inform them of their child’s progress to date with a view to supporting their learning over the remainder of the year.”

The email also referenced assessment guidelines for Option 4 that were developed in collaboration with the Vancouver Elementary School Teachers’ Association.

The guidelines call on teachers to use their “professional judgment” when assessing students and to not measure students against a proficiency scale when there is insufficient evidence of their progress.

But that doesn’t mean teachers can’t say anything about the student’s progress. “Teachers can, for instance, comment anecdotally on the student’s participation and engagement in posted assignments and in the check-ins as well,” the guidelines read.

At a Feb. 10 meeting of the district’s student learning and well-being committee, Richard Zerbe, another director of instruction, said the district is aware of concerns, specifically for Option 4 students in Grade 7 who are transitioning to high school next year.

“We’re going to be putting extra focus on supporting those students,” Zerbe said at the meeting, including providing video and virtual high school tours.

That’s good for Grade 7 students, said Martins, but what about kids like his daughter in Grade 6?

“If we had more time and energy and ambition, we’d probably take it to the province,” Martins said, but instead they’re taking their questions and advocacy for Option 4 students to the district.

The extra focus on Grade 7 students is too late for Wagner. While her son’s principal has offered to contact mini schools to advocate on his behalf, Wagner decided to move her son to the digital distance learning program, the Vancouver Learning Network, last month.

The difference between the two programs is stark, she said.

“They’re so clear: they even explain, when you hand in your work, what would be graded as a one out of four, two out of four, three out of four,” she said, adding her son has a dedicated teacher available any time via email, plus video meetings.

“There’s a rubric for them to understand how they’re going to be marked.” ![]()

Read more: Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: