Challenging, lonely and exceptional. These are the three words former Liberal MP Celina Caesar-Chavannes uses to describe being a Black woman in politics. Why? Because “representation matters,” she tells me.

During her time in office, Caesar-Chavannes was forced to push back against the status quo and lobby for legislation that would encourage equity. In return, she says she was met with sexism, racism and tokenism.

In the end, after a reportedly “explosive” conversation with a possibly tearful Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the Whitby MP resigned from the Liberal party caucus in 2019 and decided not to run again.

Was this not the same government that peddled intersectional feminism as its brand of politics? Was this not the same government that claimed it would do politics differently?

“Well,” says Caesar-Chavannes, “they weren’t woke yet. That’s all I can say. In 2020, they got woke. They didn’t get the coffee brewing. They didn’t get the eggs over easy. I laugh about it, but seriously, [anti-Black racism] wasn’t the thing to talk about at that time.”

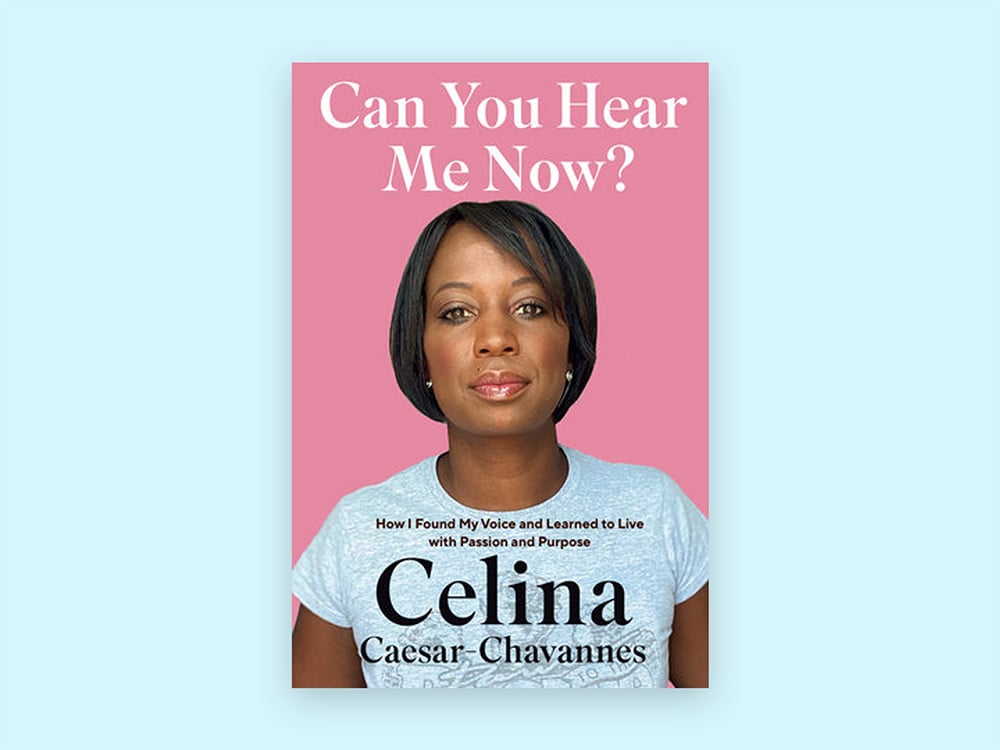

It’s being talked about now, and Caesar-Chavannes’ new book, Can You Hear Me Now? offers a front-row seat to the conversation.

It also represents her first step in a journey of vulnerability, self-healing and empowering others.

Her favourite chapter is titled “Get Off the Damn Bus and Out of Your Own Way.” It invites readers to analyze how they hinder their own progress, happiness and growth, and encourages them to ask themselves how they can do better. It’s a process Caesar-Chavannes is familiar with and one she had to embody to get to this point.

Equally important, the book is a chance for her to set the record straight.

Caesar-Chavannes’ time in government included a tense professional relationship with Trudeau. When she resigned and accused Trudeau and his office of repeated incidents of tokenism, Caesar-Chavannes claims Trudeau blew up at her. (The Prime Minister’s Office has denied any hostile exchange.)

She responded by asking him, “Motherfucker, who the fuck do you think you’re talking to?”

Another time, she called out former Conservative politician Maxime Bernier for extolling a “colour-blind society” over social media. Snapped Caesar-Chavannes: “Do some research... as to why stating colour blindness as a defence actually contributes to racism.” Then she added: “Please check your privilege and be quiet.”

Such fierce, unapologetic energy also resonates throughout her book. Whether she’s reflecting on her childhood as a Caribbean immigrant growing up in a cold, foreign country, or as a Black woman in government, Caesar-Chavannes refuses to back down from addressing difficult issues or calling out problematic people. Even more so, she understands the importance of aligning purpose with accountability and action.

When I ask her the one piece of advice she would give to her younger self, she tells me, “Don’t change a thing, Celina. Every single part of this journey has been an opportunity to learn and you’ve learned. And if you could see where you are now, it’ll be quite OK.”

I connected with Caesar-Chavannes last week, when her book was released. The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: You were the parliamentary secretary to the prime minister from 2015 to 2017. What were your first impressions of him and how did that view evolve over the years?

Celina Caesar-Chavannes: As a colleague, my impression of him was what he was selling, which was related to his politics, and not necessarily to his personality or to him as a person. But he was selling a product — a bold, transformative, open government that was going to do politics differently. So I’m not sure if that was him, necessarily, but it was the brand that he was peddling.

And it sounded good. It sounded like something I’d be interested in. It sounded like [the Liberals] were interested in looking at issues and policy from an intersectional feminist lens. Because of course they kept talking about feminism and they kept talking about diversity. And you put those two together, that’s what you have.

So I thought, “OK, this is pretty cool. I guess I could get on this train.” And then I kind of realized as I kept driving along on the train that perhaps they weren’t as intersectional feminists as I thought. Maybe it was just the word feminism and just the word diversity, and not much more substance underneath that.

You left the Liberal party disillusioned with Trudeau’s brand of politics. What pulled you to the Liberals initially?

It was exactly that. It was that brand that they were selling. And previous to that, my parents came to Canada with the previous [Pierre Elliott] Trudeau [in power]. And there’s always been this affinity towards the Liberals and the Trudeaus. I’ve always voted Liberal.

And quite frankly, I have this allegiance — or had this allegiance — to the Liberal party, irrespective of thinking through whether or not they learned about what they were talking about. And then this whole idea that they were going to do government differently, and that they were actually about diversity and about feminism. And that was something that I really want to be a part of.

Those three years of Trudeau Liberals’ politics obviously rubbed you the wrong way. What particular policies did you want to see in action when you went to Ottawa that didn’t happen?

The one that I continue to talk about is repealing mandatory minimums [on jail sentences], which was a 2015 promise. When we look at our federal prison system, the Indigenous population is eight per cent in Canada, but it comprises 25 per cent of those incarcerated in federal prison. The Black population is 3.5 per cent in Canada and occupies around 10 per cent of prisons. You would think with that glaring disparity — someone who takes a knee, someone who is apologetic about blackface — would do something about that and would take that into consideration and not further try to destroy families and destroy lives.

The second would be the increase of more Black individuals within the federal public service. Right now, we see that there’s a class action lawsuit that was filed by Black employees related to the harassment and bullying that they’ve received in the federal public service. And again, if we’re just going to keep writing on pieces of paper that we need to make changes to our federal public service, we need to comply or explain why boards don’t have enough diversity.

But within our federal system, [Black people] are still not benefiting from those promotions or from those advancements. What are we really doing? And I think those challenges were the ones that I really took to heart the most.

After speaking so much about these particular policies, why didn’t they happen?

I think it’s about power. I think that whether we’re talking about mandatory minimums, the last first-past-the-post [election], bringing equity into Black communities, or giving Indigenous nations the right to self-govern, it’s about political expediency. Will we poll well? Will we win the next election if we do the right thing? And sometimes doing the right thing is not politically expedient. It will not poll well. It will not put them in the favour of winning the next election. And so it’s not done.

How do you reconcile that? How do you reconcile that as an individual within government, someone who has not only sold a bag of goods around “politics done differently,” but also went into the 42nd Parliament with a 180-plus majority?

If we wanted to repeal mandatory minimums, if it was a priority for us, it would have been done. If we wanted to have this election as the last first-past-the-post, it would have been done. The fact that it’s not done really makes you question, “Why wouldn’t you do it? What would have been the sudden change?” The prime minister didn’t just drop into politics on the day of the election, he was born into it. So he had time to study it. All of a sudden you get there and it’s like, “Oh no, no, no, this is not good for me.” I mean, people really need to think about that.

Can you name a specific moment when you decided enough was enough?

It would have been after the situation with Maxime Bernier. There was a three-week gap between me telling Maxime Bernier to check his privilege and be quiet, and the hashtag #HereforCelina, where the support for me and calling out racism went viral. It was a three-week gap. Then everybody said, “Oh, we support Celina.”

But what happened in those three weeks before? I challenge people to just look at the record. Just look at how many Liberals supported me during that time when I was gaslit, when I was being called “the most racist MP,” when I was being criticized by mainstream media and when I was being thrown to the wolves. Where was the Liberal party? Where were these “diversity and feminism is the best thing ever” colleagues that you would think would support the one Black woman not just in their party in government, but in Parliament? Where were they? Where were the tweets of support? Where is the moment where someone said, “Let’s not just support Celina, but support the budget. Let’s support this investment in Black communities.” Where was that?

It didn’t happen. And that was the moment where... I talked about it in the book about that Nina Simone song: “You’ve got to learn to leave the table when love’s no longer being served.” My job was now no longer to appease the party, but to work for my constituents.

Party politics always seem to disproportionately affect women and people of colour. But why do you think your white colleagues have such a tough time with you speaking about anti-Black racism?

Well, they don’t have a problem speaking about it now. They weren’t woke yet. That’s all I can say. In 2020, they got woke. They didn’t get the coffee brewing. They didn’t get the eggs over easy. I laugh about it, but seriously, it wasn’t the thing to talk about at that time. So, they’re not going to talk about racism when it’s not cool.

It literally is like a high school where everybody’s jockeying for the teacher — who’s the prime minister — to pay attention. “Pick me. Pick me to be minister. Pick me. Pick me.” Nobody wants to do the thing that is going to create waves. Nobody wants to do the thing that’s going to actually be awkward to talk about. You want to sort of talk about diversity in general and feminism in general, but when I talk about things like intersectional feminism, there’s, “Oh, you know, intersectionality is such a hard word. My constituents don’t understand that.”

What was the spark that woke them?

George Floyd. When the whole world is now talking about racism, of course. But in 2018, when I’m talking about it as someone who’s a Black woman within their political party and talking about racism from a Canadian perspective, it’s, “No, no, we don’t want to talk about it. We could talk about it when it’s U.S.-focused. But we’re not going to talk about it now.”

Look at the modern-day lynching of George Floyd. You have individuals who cannot articulate what systemic racism is. You have individuals who are still denying that it exists within the very institution [policing] that was created on exclusionary policy, in the same institution that excluded women, that excluded Black people and excluded Indigenous people. “Oh, it doesn’t exist,” and “I don’t know what it means.” Why don’t you just point to the Indian Act? There are so many things to point to. They just refuse. Now that it’s a global conversation, they want to talk about it. But in 2018, they weren’t ready.

You’ve mentioned before that colleagues of yours, namely Liberal MP Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, have been able to criticize the government, but received little punishment in comparison to female MPs. Obviously, privilege plays a huge role in politics. How do we combat that moving forward?

I would say something as simple as get more women elected, but I just don’t know that that’s the formula. Because if you get more women elected, but you add women and maintain the status quo, then what’s the point? I think we need to get more individuals who understand electing those who are actually going to act.

When we talk about being anti-racist, it’s about the act of ensuring that every decision you make is one that creates equity. So we need individuals who actually understand how to act towards equitable outcomes.

I just don’t know if saying “elect more women” or “elect more women of colour” is going to do that. We need people who are going to act, who are not afraid to challenge the status quo on issues that never get talked about and are always pushed to the side.

How do we hold them accountable when they push issues to the side?

The whole meaning of democracy, from the Greek word, is power of the people. And the people have the power to make those changes happen. Democracy is the power of the people to make change. Now, whether we are deciding that this issue is important enough to rattle the cages and sway political will is a different story.

The power has always been with the people. It has never belonged to a politician. And I think that’s what I want Canadians to understand, especially on this issue. Especially when people were blacking out their Facebook pages and their social media and putting #BlackLivesMatter. We need to act.

We can’t have a class action lawsuit within the federal government and Canadians not totally rallied around that. We can’t have disproportionate numbers in prison systems and Canadians not rallied around that. We can’t continue to have racism that impacts our children in a child welfare system that has 40 per cent Black children housed in the city of Toronto and not have everybody rally around that.

It would seem that a lot of Canadian politics centres around performative allyship. Why do you think that is and why has it been able to persist?

A couple of weeks ago, a number of different Black organizations across the country received a letter from Employment and Social Development Canada that indicated they were not receiving funding because they couldn’t demonstrate that the leadership of the organization was Black, basically saying, “You have to prove that you’re Black or you’re not Black enough to receive this funding.” These are organizations like the Ontario Black History Society, Black Lives Matter Ontario, Operation Black Vote and many others. Clearly the leadership of these organizations [is] run by Black people!

There is an absolute disregard for Black communities within our federal system. And that’s probably the reason why I’m going to bring up this class action lawsuit again, because Black individuals have been barred from receiving promotions. Some working within the federal government for 20 or 30 years... never receiving one promotion.

So now, when you’re looking to fund these organizations, you don’t have people around the table to say, “Yes, I know Ontario Black History Society. Mrs. Henry? I know that she’s Black and at the head of that organization. I know Velma Morgan is Black from Operation Black Vote.” No, you can’t. You don’t know any of these.

That’s because our system is so diseased with systemic racism that in order for it to change, you actually have to deconstruct it and build it back up again. That’s why I think that this lawsuit is so particularly important, because it actually makes the federal government sit up and pay attention. They’ve never been held accountable. That’s why it continues.

You left very close to the SNC-Lavalin scandal, which resulted in fellow Liberal MPs Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott being expelled from the Liberal caucus. Did the scandal influence your decision?

The scandal did not influence [my] decision to leave... the decision for me to sit as an independent was influenced by some of the actions of SNC. But the decision for me to not run again, that was made before SNC.

Why do you think the media lumped your departure with SNC? Why wasn’t your story told separate from that?

Because it’s easy. It’s lazy. The second [reason] is that I was very vocal and supported Jody. We had just come out of a #MeToo movement where we support women, where we say if women are being harassed or bullied, we need to believe them. And then all of a sudden, the Liberals are leaving her. But it wasn’t politically expedient for them to stay with her or believe her. So me speaking out and supporting Jody... of course it makes it easy for people to lump it in and say that one has to do with the other.

But to be honest, the ability for them to dig into my story a little bit more was there. I made it very clear that my decision was not related to SNC. But SNC was the story of the day. So you lump it in. And that’s why it was important for me to write my book and my own story, and make sure that the issues that I had were on the record. I couldn’t trust that history would be kind enough to tell that version.

Did writing the book come from a place of fear of not having your story told or having your story told incorrectly?

It’s interesting because the Ontario Black History Society did a campaign around #BlackedOutHistory. They looked at a history textbook that would be used in schools. And they blacked out all the pages that didn’t have any references to Black history. The book was over 200 pages long. They blocked out close to 99 per cent of that and found that only 13 pages had any reference to Black history.

So when we talk about having our story not told, our stories have always been erased from the consciousness of Canadians and from the textbooks of Canadian history for as long as we’ve been here.

So me having the opportunity to write my story was critically important. I think when writing the book, it was less about politics, to be quite honest. Politics has been such a small part of my life but has been blown up, of course, because I’m a public speaker.

Writing the book was more about telling the story of making mistakes, dusting yourself off and getting back up. And I really wanted people, especially women of colour, and in particular Black women, to see themselves in the story, and to know that I see them.

This exercise of being in politics has opened my eyes to so many injustices that women in our community face, that I really didn’t have a choice but to document that experience and give records to not just people who are living now, but those who come in the future. These are some of the things that may happen. These are some of the lessons that I learned. And these are some of the ways in which you can navigate the space, such that you could preserve your mental health and build your resilience. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Federal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: