A first-of-its kind safer supply clinic in Vancouver’s downtown will begin to offer flexible, individual-centred care to people who use a variety of substances as early as this spring.

The $5-million, four-year Safer Alternatives for Emergency Response program was one of four B.C. safer supply projects to share $15 million, the federal government announced today.

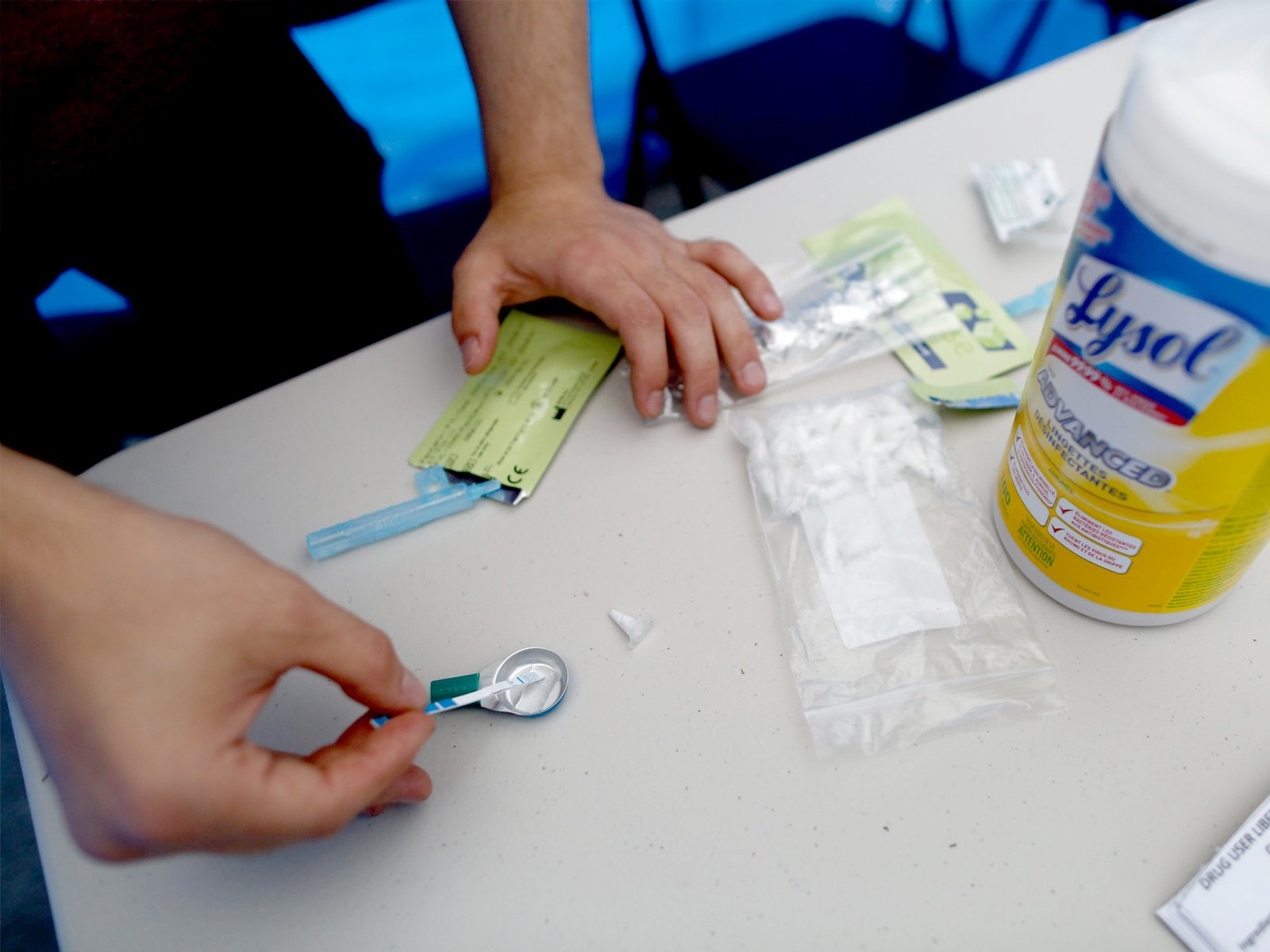

The projects will provide pharmaceutical-grade medication as an alternative to the poisoned illicit supply.

“This can help not only Vancouver Coastal Health, not only B.C., but the rest of the country in identifying new models for preventing overdose deaths,” said Coastal Health chief medical officer Dr. Patricia Daly.

The government also announced funding for three similar projects, two in Vancouver and one in Victoria.

Over the next three years, $3.6 million will go to the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Providence Health Care Research Institute to run a safer supply and support services program in the Downtown Eastside.

The Kílala Lelum Urban Indigenous Health and Healing Cooperative will receive $2.8 million over three years to operate safer supply and Indigenous Elder-led cultural healing programs at the co-operative in the same neighbourhood.

And about $4 million over three years will go to AVI Health and Community Services in Victoria for safer supply programs.

Safer supply programs aim to reduce overdoses and deaths by providing substance users with alternatives to the increasingly toxic illicit drug supply by prescribing pharmaceutical-grade substances to users.

The four-year SAFER project will be run in partnership with Portland Health Services, Vancouver Coastal Health and the BC Centre on Substance Use in order to develop new models for successful safer supply delivery.

PHS’s director of programs Susan Alexman said there are a number of barriers that make current safer supply models difficult for some people to access.

“Is [the difficulty] coming into the clinic all the time, is it that you had a reaction to it, is it that the dosage wasn’t right?” said Alexman. “It’s looking at all those types of factors and working with the individual to prescribe something different and work on something better.”

Daly noted some clients may be able to take doses home instead of coming to the clinic multiple times per day. But solutions will differ depending on client needs.

SAFER will also embed peers with current or past experience with substance use in all parts of the operation in order to reduce the effect of stigma many substance users experience when seeking care.

Wrap-around supports for housing, employment and other health needs will be integrated into the clinic.

“Our goal is to really look at the individual in totality, not just in terms of their safer supply needs, but also ensuring they have access to other needs and that they continue to be successful,” said Alexman.

Daly and Alexman said the model aims to be flexible and scalable for other communities in B.C. and across Canada and provide lessons as the BC Centre on Substance Use completes its ongoing evaluation of the pilot.

“We want clients to be able to tell us they feel safe and listened to and that they had some choice in the medical care they were given,” said Alexman. “And that they have power over their own prospects and their decision-making and their health.”

The federal government’s financial support for safer supply initiatives comes a week after it agreed to discuss decriminalizing possession of illicit substances for personal use within Vancouver city limits.

“People can and do recover, if they have the right support, but the first step is to keep them safe,” said Vancouver Centre MP Dr. Hedy Fry. “Meeting someone where they are ensures they get the physical and mental help they need.”

Fry also said securing a domestic supply of pharmaceutical grade heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine, is “at the top of the list of things being looked at by Health Canada.”

Daly said diacetylmorphine can be an essential alternative for people with high tolerances or who are addicted to the powerful opioid fentanyl.

A wider variety of available substances give individuals more choice and the opportunity to find a routine that works for them, making them less likely to access the street supply, Daly and Alexman said.

“Right now, to determine what works best for someone, that is also based on what other kinds of pharmaceuticals are available,” said Alexman.

But the programs will all be waiting for action on B.C.’s September announcement, days before the provincial election, that it would vastly expand the types of substances and eligibility for safer supply.

More than four months later, that hasn’t happened.

Currently, eligible substance users are most often prescribed opioid substitute hydromorphone in tablet form. Most then crush, dissolve and inject the substance.

The province said about 23,000 people have availed themselves of some form of prescription alternative in the last year, including 3,348 people who were prescribed hydromorphone as of December. Research from the BC Centre for Disease Control in 2012 estimated as many as 83,000 people in the province were opioid-dependent almost a decade ago.

For those who hydromorphone doesn’t help, injectable suboxone, methadone or limited amounts of diacetylmorphine may be used.

Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson said doctors, pharmacists, nurses and their colleges are working toward implementing the province’s promise of expanded safer supply.

“We are not going to be moving forward until we’re confident that patient safety is at the forefront,” she said.

Alexman and Daly hope SAFER will benefit from an increased array of substances as they seek to give substance users the same level of autonomy and choice as people with other health conditions.

“We’re not telling people, ‘You’ll use injectable hydromorphone.’ Now we’re saying, ‘What might work better?’” said Alexman. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: