For corporations like Telus and Well Health moving into providing primary health care, the real opportunity may be in using their new relationship with patients to build other parts of their businesses, particularly as providers of digital health records.

That’s the assessment of Rita McCracken, a family doctor who practises in East Vancouver, who provides care in a nursing home and teaches at the University of British Columbia. She sees a longer-term strategy playing out.

“Do you think Telus thinks it’s going to get rich on the fee-for-service fees, or do you think they’re much more interested in the incredibly rich health data that they’re able to acquire through acquisition of primary care?” she asked.

Like other family doctors interviewed for this series, she observed that clinics are so marginal financially that it makes little sense for corporations to make acquiring them a priority.

“I think it’s part of a much larger strategy,” McCracken said. “It is not just to turn the doctors into fee-for-service generators, but rather it’s to create an interface that allows for collection of data to roll out new products, to engage in corporatized research, like around personalized genomics, personalized medication plans, personalized cancer treatments, personalized screening programs.”

Already medicine is moving towards providing care for everything from diabetes to Alzheimer’s disease that’s tailored to individuals, particularly based on their genes.

It’s much more likely that corporations see those possibilities — and the possibility of immense profit — as the reason to get into primary care, McCracken said.

There’s no question that corporations have been growing the parts of their businesses dedicated to collecting personal information in health databases.

Those databases would include some of the most sensitive information about people, details many would want to remain private, including about their mental health, addictions, sexually transmitted illnesses and whether they’ve had an abortion.

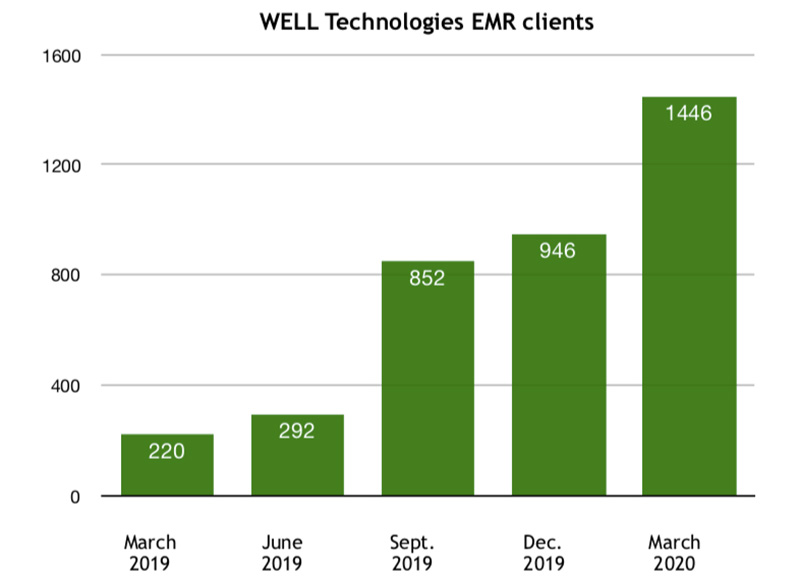

A year ago, Well Health said it had become the third largest provider of electronic medical records in Canada. Since that time the number of clinics it provides EMR services to has increased by 70 per cent.

Telus also has a major electronic records business and provides services to about 45 per cent of community-based physicians in Ontario, for example. The company advertises itself to doctors as “the nation’s largest digital health-care provider.”

The involvement of corporations in holding sensitive medical records is a concern for at least some patients. On the Apple App Store, many of the reviews of Telus’s Babylon telehealth service express distrust about how the company manages digital records.

As one user wrote in March, “Copy of all your video conversations with doctors — check. Data stored in unfriendly regimes and forever — check.”

Another user suggested reading the terms and conditions carefully. “They sell your medical information,” the user said. “No thank you!”

In Alberta, the province’s privacy commissioner Jill Clayton announced in April she had launched two investigations into Babylon to see if the app complies with the province’s privacy laws.

Telus provides the app in Canada in partnership with Babylon Health, a company based in the United Kingdom that has some 2.3 million registered users. In June Babylon admitted to a privacy breach in the U.K. where some users could watch video recordings of other users’ consultations with physicians.

Marcy Cohen, a community researcher who has worked on issues around primary care and community care for two decades, said there needs to be greater scrutiny and more regulation of Telus’s health businesses, starting with how the company collects and uses data.

“I think the strongest and most obvious argument is the extent to which you have to sign consent forms,” she said. “Those consent forms are setting it up so that your information can be shared and sold and manipulated and analyzed, and it’s really an opportunity for profit seeking.”

The company is acting in an environment where the privacy protections are relatively weak, she said. “In Canada we don’t have anything like the health data protections they have in Europe, so once someone has your data, as they possess it they own it, they can share it, they can sell it and we never know anything about it.”

While there are some strong privacy controls within the public health authorities, she said, “in this part of the health system it’s the wild west and people have no knowledge of that and no awareness of that.”

Telus forwarded requests for comment to a public relations company that responded on the company’s behalf.

“Protecting patient data is the cornerstone of our health-care business,” they said, adding the company takes “every necessary precaution” to make sure people’s personal information is secure.

“The health and medical information that users share and receive through our services, including symptoms, treatments, test results and consultations, are stored in Canada and securely transmitted using encryption mechanisms that meet, and in some cases exceed, the highest industry recognized standards,” they said.

According to the spokesperson, the data the company collects through its services are only used to provide care and is shared only in cases where it is permitted by law or the patient has consented. “These include necessary medical purposes, such as suggesting a best course of action, diagnosis and treatment, or for example, sharing clinical data upon a patient’s request with another health-care provider,” they said.

“Personal data is never shared with any other organization without a user’s explicit consent and are held with technical and organizational security in compliance with the maintenance of Canadian health records.”

The detailed privacy policy for Babylon is posted online and in relatively plain language explains how the company uses and retains people’s personal information, including both to provide them a service and to look for ways to improve the products it offers.

Well did not respond by publication time to detailed questions.

Well’s financial filings acknowledge that it’s difficult to ensure privacy of digital records, noting employees and consultants with Well and its subsidiaries necessarily have access to clients’ medical histories.

“There can be no assurance that the company’s existing policies, procedures and systems will be sufficient to address the privacy concerns of existing and future clients whether or not such a breach of privacy were to have occurred as a result of the company’s employees or arm’s-length third parties,” it said.

“If a client’s privacy is violated, or if the company is found to have violated any law or regulation, it could be liable for damages or for criminal fines and/or penalties.”

B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix said there are benefits to moving to electronic medical records, but they come with risks no matter who owns and manages them.

“Every single day, every minute of every day, people are probing those systems to find weaknesses,” Dix said. “Health-care records are the subject of almost constant efforts by people who are seeking to steal them.”

Keeping records electronically means patient data can be accessed by caregivers in different locations and errors can be reduced, he said, and patients can see their own records. But providing that kind of relatively wide access creates a security challenge.

“How do you open up systems so that you can see your test results, not just have to see them interpreted by someone, but see your own test results, and on the other hand how do you protect those records?” he said. “It’s going to be an everyday job for health systems for the next, well for the rest of my life and well beyond that.”

Dix said he was less concerned about the possibility of providers like Telus or Well selling people’s records. “That wouldn’t and shouldn’t be allowed in almost any jurisdiction,” he said. “There are obviously strict rules around privacy around those questions.”

Still, whether in the public or private sector, there are breaches, Dix said. “There are risks to electronic medical record systems of all kinds, there’s no two ways about that.”

In B.C., there have been long-standing concerns that the province’s laws aren’t robust enough to protect people’s sensitive health information.

An April 2014 special report by the province’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner made 21 recommendations for the government to implement.

“B.C.’s current legal framework for the use of personal health information is increasingly strained in the digital era,” then commissioner Elizabeth Denham wrote in the introduction to A Prescription for Legislative Reform: Improving Privacy Protection in BC’s Health Sector.

“The current laws have developed incrementally over the years and are spread across many statutes. The result is a complex web of rules and regulations that are, in some cases, difficult to understand and result in a lack of transparency for the public about how their information is being used or shared.”

The government never acted on the report’s core recommendation to introduce a comprehensive health privacy law, and there still appears to be a patchwork of at least eight laws that apply.

Like his predecessor the current commissioner, Michael McEvoy, supports comprehensive stand-alone health privacy legislation, a spokesperson for his office said.

Jason Woywada, the executive director of the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association, said the government should implement the commissioner’s recommendations so that people can clearly understand how their sensitive health information will be handled.

Given the patchwork of legislation and the history of breaches like the recent LifeLabs one, he said, “We’ve got to find a way to restore that trust between appropriate access to information and protection of people’s privacy.”

Consumers using a health-care service like Telus’s should be given an opportunity to provide informed consent to how their personal information may be used, and they should avoid using a service if they’re not sure their privacy will be protected, he said.

“Informed consent is under a lot of scrutiny right now, and what constitutes ‘informed consent,’” Woywada added. A wide variety of people use health services and they have differing abilities to understand what they are consenting to. “Unfortunately, one document doesn’t meet everybody’s needs to give informed consent.”

A Doctors of BC document updated in August 2017 lists various uses for health information, including not just patient care, research and quality assurance, but also commerce.

“Protecting patients’ personal health information is a priority for physicians because it is fundamental to maintaining the physician-patient relationship,” it said.

“If patients do not have confidence that their physician has adequate safeguards in place to protect their personal health information, they may refrain from disclosing critical information, refuse to provide consent to use personal health information for research purposes or not seek treatment.”

It cited a Canadian Medical Association survey that found 11 per cent of patients withheld information from a health-care provider because they were concerned about with whom it would be shared and what it would be used for.

Regardless of whether people’s information is actually at risk or is being misused, the concern about it is enough on its own to affect what people will tell their care provider — and that will affect the care they receive and ultimately their health.

A confusion of laws won’t ease their concerns. Nor will entrusting that information to Telus, Well and other corporate providers. ![]()

Read more: Health, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: