Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Vancouver company Well Health Technologies Corp. was growing rapidly and had ambitious expansion plans.

Some investors saw an opportunity. But other people saw a threat to public health care.

Well had, over a couple of years, acquired 21 primary care clinics in B.C., become the electronic medical record provider to another 1,446 clinics across Canada and dedicated a significant marketing budget to promoting its services.

Well is something new, a Canadian company focused on providing direct health-care services and traded on the stock market.

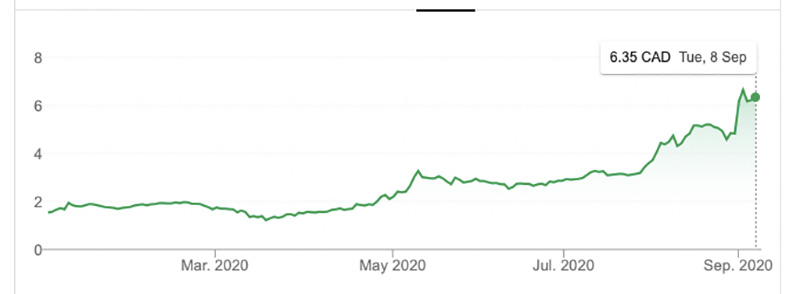

Investors have been enthusiastic, bidding up Well’s stock price. Shares that were worth 25 cents a little more than two years ago had risen to about $2 by early this year. The COVID-19 pandemic brought more interest, and shares topped $6 by Sept. 1.

By September, Well was worth about $790 million and looked set to keep growing.

But what may be good for investors is likely going to be bad for patients, said Marcy Cohen, a community researcher who has worked on issues around primary care and community care for two decades.

“They’re obviously trying different strategies about how and where the profit possibilities are,” Cohen said. “Because they’re a corporation, their responsibility is to their shareholders. They are looking at health care as a revenue generating opportunity, so they’re looking and experimenting with all the different ways they might be able to make a profit out of health care.”

Private entities have been providing health care in Canada for years, but they have tended to be small and run by physicians who put the priority on patients, not shareholders, she said.

With Well’s establishment, Canada is entering a new world of marketing, advertising and corporatization in health care.

“I think it’s potentially a huge shift and very problematic and is the reason there are so many mainstream physicians’ organizations trying to respond,” Cohen said.

Nobody from Well was available for an interview.

Pardeep Sangha, the company’s vice-president of corporate strategy and investor relations, asked for detailed questions by email but didn’t respond to them by publication time.

Sangha did send a June presentation for investors and reports on the company from three stock analysts, all of which focus on the strength of the company as an investment. There’s also a wealth of documents filed with regulators on the company’s finances and plans.

According to that financial reporting, Well sees itself as part of the solution to improve health care. “Well aims to positively impact health outcomes by leveraging technology to empower and support patients and doctors,” it said in its most recent quarterly report filed May 15.

Well also sees a business opportunity. Health-care delivery in Canada was worth $242 billion in 2017 and 15.4 per cent of that, about $37 billion, was spent on physicians, it told investors.

“The company’s overarching goal is to consolidate and modernize primary health-care assets using digital technologies and processes that improve patient experience, operational efficiency and overall care performance," it said. “Well intends to address the issue of fragmentation in the Canadian health-care system which management believes has led to a lack of digitization of primary health-care clinics.”

Observers suggest the approach is similar to what corporations have done in other industries, including veterinary hospitals and funeral services.

Well has officially existed since 2010, but it’s only since 2018 that it has focused on primary care clinics and related services, discontinuing its previous endeavours Canada Yoga Inc. and Shakti Yoga Apparel LLC.

Company materials highlight the investment Li Ka-shing of Hong Kong, the 35th richest person in the world according to Forbes Magazine, has made in the company.

It also talks about the track record of chairman and CEO Hamed Shahbazi, who previously founded TIO Networks Corp. and grew it into a major provider of bill payment services before a sale to PayPal Holding Inc. in 2017 for more than $300 million.

Since 2018, Well has grown by buying clinics and electronic medical records companies. Well now owns and operates 21 clinics and provides EMR software and services to some 1,500 clinics. It also owns a 51-per-cent stake in SleepWorks Medical Inc., a company in the business of diagnosing sleep disorders and selling the equipment to treat them.

This spring, Well opened a dermatology clinic in North Vancouver under the brand name “Derm Lab,” where three doctors will provide medical and cosmetic services.

And in March, as the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Canada, Well launched VirtualClinic+ to connect patients and physicians using video, phone and secure messaging, allowing patients to avoid sitting in a clinic waiting room.

“These capabilities are designed to support continuity of care, improve accessibility to quality care and ultimately drive better health outcomes,” the document said.

Well now has hundreds of people providing care through its VirtualClinic+ program and can handle more than 1,000 appointments a day, which in turn has allowed the company to cut costs and increase its profits.

“Going forward Well anticipates that physicians will be operating in a hybrid model of seeing patients in-clinic as well as using telehealth,” the company’s quarterly report said. “In this scenario, physicians aren’t required to be in the office as much; therefore, each clinic can support more physicians than before.”

It announced plans to close a clinic in Surrey and relocate the physicians to other clinics the company owns nearby, “thereby maintaining revenues and increasing the utilization in our other clinics and improving our overall EBITDA [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization] profile.”

In other words, it anticipated being able to close the clinic and consolidate services in other clinics, each of which would become more profitable.

In the three months that ended in March, Well had $10.2 million in revenue. The majority of that, $6.8 million, came from providing publicly insured services. Well says it pays staff doctors about 70 per cent of the fees received from the province.

Another $1.7 million was paid directly by patients or third parties for services not covered by the province’s Medical Services Plan.

Digital services provided another $1.7 million, 10 times higher than a year earlier, the company said.

The company’s documents are also clear about the ambitions for continued growth.

It intends to expand its clinics from B.C. into other parts of Canada and to continue expanding its telehealth program “not only as a defensive strategy to mitigate against any potential decreases in its onsite clinical business due to COVID-19 physical distancing requirements, but also as an offensive strategy to grow its share of the expanding telehealth market in North America.”

According to the company’s documents, there is a “strong pipeline of potential acquisition targets to drive its inorganic growth strategy.” Due to COVID-19, it said, it would likely increase its focus on investing in technologies and services that could be provided remotely.

Baldev Sanghera provides community care in Burnaby, including at a physician-owned clinic. A family doctor since 1997, he sees how Well’s corporate clinics are already changing the landscape.

“I think they’re a very big threat in that they have a lot of marketing behind them,” he said, adding neither the public nor physicians have recognized what’s coming.

Since buying clinics in the Lower Mainland, Well has laid off frontline staff and sought efficiencies, he said. Physicians working in the clinics have had to focus on seeing more patients, and are generally less satisfied with their work, Sanghera said.

For patients, the care they get is comparable to fast food, he said, though many won’t know what they’re missing. “If the only thing that’s been advertised to you is McDonald’s, then that’s a great meal.”

Ultimately, it’s a question of resiliency and how to deliver primary care in a way that puts the needs of the community first, Sanghera said. “The pandemic has shown us having a corporate outlook on community life doesn’t give you the tools.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: