Dario Adonias wakes up each morning to the sound of a rooster crowing outside his window, nudging him out of bed and off to the grocery store, where he works selling and packing items. The trip there, which he used to do by bus, takes about 25 minutes on foot, up and down hills on a narrow and now mostly deserted road. Most days he doesn’t mind the walk — it’s time he gets to daydream about life before the pandemic, when he thought leaving this life of struggle behind was possible.

Adonias is 19, though his small frame makes him look younger. His hair is short, black, straight, his eyes dark brown. He lives in a small house with his parents, two sisters and an aunt, in Cobán, a highland city in Guatemala’s central cardamom and coffee-growing region, where The Tyee is looking in occasionally as part of a project in partnership with TulaSalud, an initiative of the Tula Foundation, which funds rural public health work in that Central American country.

While most teenagers in Canada adjust to having their social lives restricted and school mediated through computer screens, in Guatemala, being a young person during the pandemic has tended to mean more wrenching changes. Thousands of young people like Adonias find themselves in the stressful position of being their family’s sole earner during the crisis.

“My father, my sister and my aunt used to work. Because of COVID, my sister and my aunt have lost their jobs. And for my dad, it’s really expensive for him to get to work because of our lack of access to public transit. [This] makes my work even more crucial for our survival,” he told The Tyee. Watch a video conversation with Adonias below.

Like many people his age, Adonias is the first in his family to dare to dream beyond what was once possible for his parents and others before them. He’s part of Guatemala’s new generation, who after a 36-year-long civil war ending in 1996, could see a brighter future. Then came COVID-19.

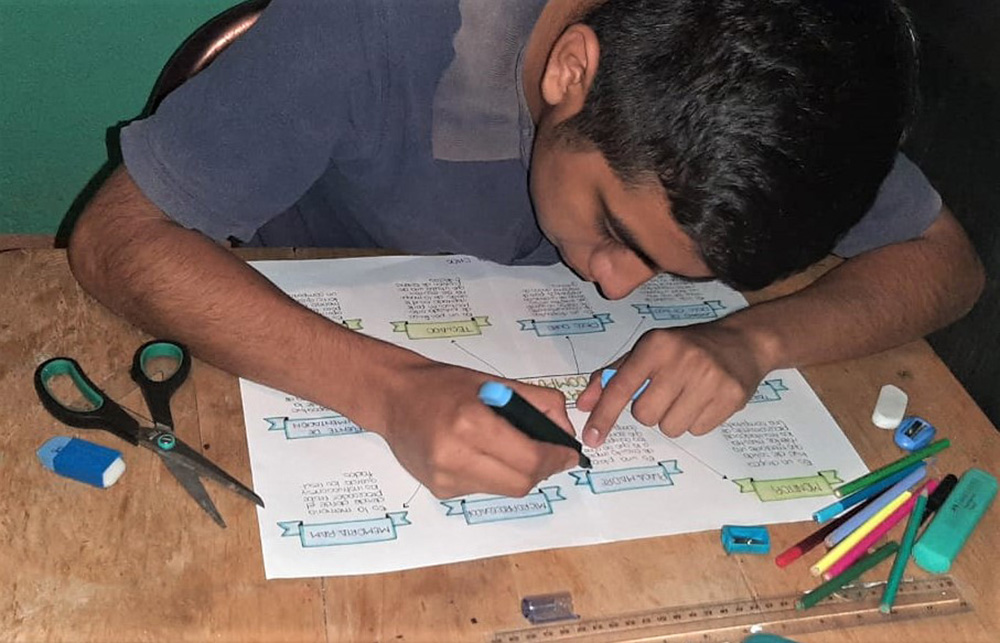

When the year started, the young shop clerk decided to enrol in a bachelor’s program in computer science by mail, after two years of being away from school due to financial reasons. “A lot of young people drop out of school to work, especially as they move up in grades. Many leave to learn a trade, where they can start to make some money early,” said Wilson Boche, a Guatemalan economic analyst who specializes in health.

Adonias’s dream was to complete the program and go on to university in the capital, where he could try for a professional career. “I wanted to keep on going, without stopping again. When I started studying this year, I thought I was ready to handle it, but then the pandemic hit, and it’s become really hard to go on. Now I’m not so sure I can finish it,” he added.

His story is one of millions among Latin America’s young generation, their lives put on hold by the coronavirus. As the pandemic whacks businesses, impedes mobility and strains governments’ capacities, youth must pitch in to support their struggling families. Many work in informal, unregulated conditions that put them at risk of contracting the virus.

And so, while Canada’s students prepare to return to school in September, many in Guatemala run the risk of dropping out entirely. For a lot of them, taking classes online is not possible. “There’s limited access to the internet, especially in rural areas, where connectivity is really low and sometimes pupils don't even have access to electricity,” explained Boche.

The social effects may ripple for years to come. “With families struggling to make ends meet, more and more young people will be pushed away from education, towards work. Many won’t finish the year. Who knows if that means they won’t come back,” added Boche. (Here is another video a young Guatemalan girl forced out of school by the pandemic.)

According to data from the 2018 census, a large proportion of Guatemala’s population are minors, as is characteristic of developing countries. About one out of three Guatemalans are between the ages of 10 and 24, compared to one out of six in Canada. For people over 65, the picture is reversed — about one out of 18 people are seniors in Guatemala, while in Canada it’s one out of six. These demographic differences help explain why the pandemic, in Guatemala and other countries in the southern cone, has tended to affect a much younger population than places like North America and Europe.

Another factor is the kind of jobs available to younger people. In Guatemala, observed Boche, “we have a young working sector who cannot afford to stay home if they still have their jobs. So, they go out and expose themselves to risk. These are people who are constantly on the move.

“What’s more, because many of these young people do not have sufficient nutritional levels to defend themselves against the virus, they become even more susceptible to complications. In the long run, this could have devastating effects to the country’s economy.”

Over the last few months, Dario Adonias has watched many of his friends lose their jobs. They, too, were working to bring money home to help their families. According to Fredy Argueta, a political analyst, it’s estimated that nearly one-third of the country’s work force has lost their jobs since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in March. The few who have been able to stay working are willing to go above and beyond to make sure that doesn’t change, even if it means putting their lives in danger.

That’s the predicament facing Adonias. “Right now, we don’t know who is infected and who isn’t. We run a lot of risk just to be able to work,” he explained.

“The truth is that I don’t have another option. If it were up to me, I would stay at home, but I have to work to help my family. I constantly think about the risk not only for myself but for my family too. This has been really hard for me psychologically, but this is a risk that I choose to take every day, taking all the necessary precautions. In the end, you have to go on.”

Starting in March, the Guatemalan government began imposing restrictions to battle the coronavirus, including closing regional and municipal borders, fining for citizens not wearing masks in public spaces and strictly enforcing curfews. Those measures intended to keep the lid on case rates have erected debilitating barriers for those already struggling. For Adonias, the curfew has cut into his work hours and pay. In a matter of weeks, he saw his income drop from 2,500 quetzales (C$436) a month to less than 1,800 quetzales (C$314).

“Pay reductions have significant impacts for poorer populations, in particular, those who might have been struggling prior to the crisis. Without an approximate date for when restrictions will be lifted, many more can fall under the poverty line, where half of Guatemalans already live,” said Argueta.

But young people defy pandemic restrictions at significant risk. If they are caught violating curfew, they may be fined or sent to jail, where overcrowding is tied to high rates of COVID-19. Last month, it claimed the life of a jailed former national health minister. But the cells continue to fill. As of early July, more than 30,000 people had been apprehended by the police and jailed for breaking curfew.

“At one point there were more people who had been detained than people who had been tested positive for COVID-19,” said Boche. Among the regions with the highest rate of police apprehensions is Alta Verapaz, one of the poorest provinces in the country, where Adonias lives.

“A lot of people have had to break curfew to get to their jobs on time or to stay until the shops close. Because the restrictions say you can’t leave your house, they don’t ask whether you need to work — they simply detain you. This is the fear most people who work have, that they won’t be able to get home in time. Unfortunately, these are the rules that are being enforced, and we try to follow them. There are instances where it’s hard to obey them,” said Adonias.

In Guatemala City, the nation’s capital, many have taken to the street to protest the strict restrictions. For now, though, there’s no end in sight to curfews.

“There’s great frustration because measures haven’t given the results that were promised,” anthropologist Mario de León told The Tyee. “People are really upset — at times aggressive, at times paranoid, at times anxious — because they need to work to survive. And most of them are working in the informal sector, where there’s a need to be face-to-face, in close proximity.”

In fact, more than 75 per cent of Guatemala’s working population participate in the informal economy. Often, these are people who are self-employed or work at odd jobs that are untaxed and unmonitored by the state. But the group also includes people like Adonias, who despite working full time at a grocery store, does not have a contract and formal status that would allow access to the subsidies and financial supports provided by government programs.

“Many of these young workers don’t have social welfare, they don’t have any protection. Only about five per cent of people between the ages of 14 and 29 have access to pension and employment insurance through social welfare. Often, these are young people, earning for a family of five or six, and that takes a toll on them,” noted Boche.

The pandemic and the shutdowns it triggered, experts have noted, are creating a shadow epidemic of mental health problems throughout the world. In British Columbia, a government survey found almost one-half of the province’s residents have experienced worsening mental health. Those aged 18 to 29 were hurting the most, mentally and economically.

In Guatemala, that age group is showing serious signs of breaking under the strain, said anthropologist León. He sees rising violence and despair. “With COVID, there’s been an increase in the rate of suicide among young people. This is possibly due to three factors: lower level of remittances from abroad, precarious work and study conditions, and the fact many have assumed the responsibility of feeding their families.”

David Beasley, head of the United Nations World Food Programme, says the COVID-19 crisis has dramatically increased the number of starving people in Latin America. Food insecurity in the region has risen by 269 per cent since the pandemic struck, he said. As of July 30, the Canadian Armed Forces have delivered multiple pallets of COVID-19 related supplies to Guatemala, in support of the UN food program and the Pan American Health Organization.

But Argueta is doubtful the aid will have the intended affect. Corruption will keep many supplies from reaching those in need, he predicted.

When Adonias looks ahead, the future he’d once anticipated with optimism seems to be dissolving before his eyes. “Things are getting worse in Guatemala, and in Cobán too,” he said. “What worries me the most right now is keeping my family fed. How will we ensure we come out the other end, if and when restrictions become stricter?”

In mid-July the government reacted to rising case counts by imposing a one-day lockdown. For Adonias and his family, the order meant reaching deep to fend off hunger, and find patience. “That’s one less day of work. We’ve seen a huge change in how we eat. All we’re focused on is making sure we have enough to eat.”

He paused for a moment, reaching for a note of hope. “I think we still have a bit more time before we can push through this.”

This article is part of a continuing series, found here. ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: