Perry Kendall wondered if it really made sense for British Columbia to create a stand-alone ministry to deal with mental health and addictions, as it did in 2017. The idea had “a great deal of political appeal,” he noted. But it might build in a disadvantage.

Why? Because “you have one ministry which is significantly smaller making policy for another ministry that has actually got the money.”

Kendall, currently the co-interim executive director at the B.C. Centre on Substance Use, brought to his perspective 20 years in public health. When the B.C. government declared the opioid emergency in 2016, he was the provincial health officer in charge.

Now, nearly three years after the creation of the B.C. Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, its critics say progress has been too slow, and it has failed to champion some of the more politically sensitive initiatives that would save more lives, particularly around the decriminalization of possession of illegal drugs for personal use and making the drug supply safer.

But the minister responsible argues that the ministry has accomplished a lot already and is making a difference, though there’s undeniably more to do.

There’s no question the ministry’s origins were political. BC NDP Leader John Horgan campaigned in 2017 on the promise of creating it so that there would be one person in cabinet who could focus on the crisis and be accountable for the government’s response.

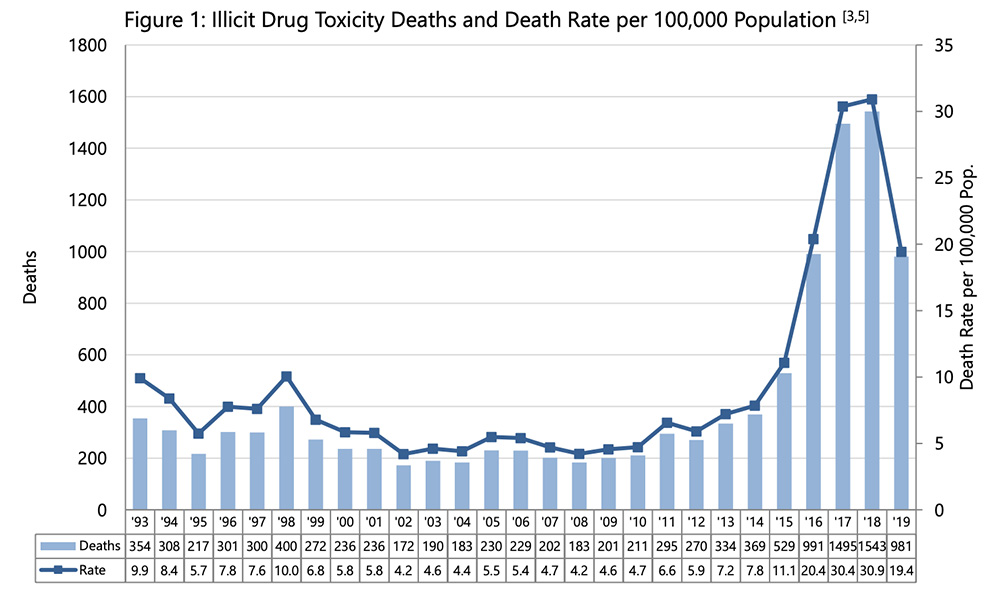

At the time, the number of overdose deaths were spiking upwards. From a few hundred deaths a year, it had risen to 529 in 2015, then 921 in 2016 (a number that has since been revised to 991 as investigations concluded).

The provincial government had declared a public health emergency and had expanded services including overdose prevention sites, supervised consumption services and the provision of naloxone, which reverses the effects of overdoses. It had also funded a joint task force on overdose response with the federal government.

But none of it was slowing the number of poisonings, and Horgan pledged, “I’ll do my level best to make sure those numbers never ever get as high as they were last year.”

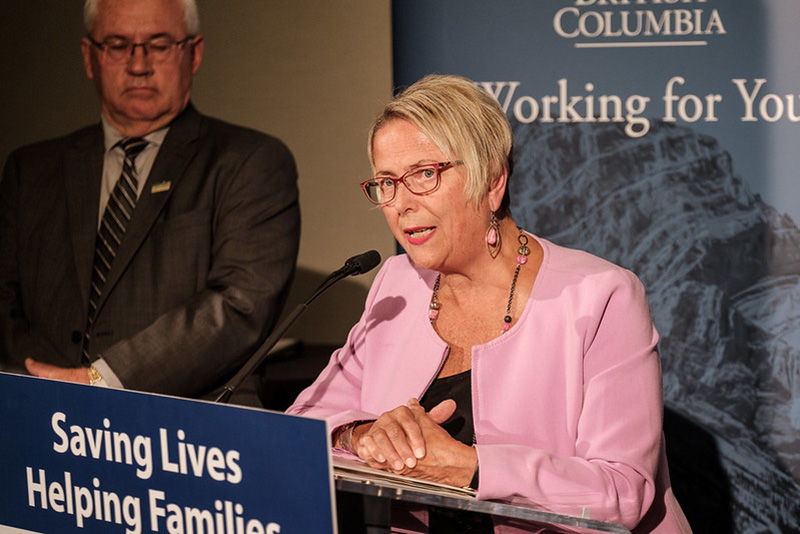

Once the NDP formed government and Horgan became premier, he appointed MLA for New Westminster Judy Darcy to head the new ministry and take the lead on the crisis.

The number of deaths kept increasing, peaking at 1,543 in 2018, before finally dropping last year for the first time since 2012. Still, the number of survived overdoses continues to rise. And even with last year’s drop, the 981 deaths last year remain higher than in 2016 when the emergency was declared.

The statistics speak to thousands of human tragedies, each of them affecting an individual and the people around them. As B.C.’s chief coroner, Lisa Lapointe, stressed in releasing the most recent numbers Feb. 24, “Those that died of drug toxicity this year were more than statistics, they were people. They were loved. They had hopes and dreams and challenges, just like the rest of us.”

Clearly, as the current provincial health officer Bonnie Henry observed, “This is a crisis that continues.”

As it rolls on, people on the front lines echo the concerns Perry Kendall has voiced about the creation of a standalone ministry.

“It’s so underfunded,” said Ann Livingston from the B.C. and Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, “and it’s been cleaved off from the Ministry of Health.”

‘Long way to go,’ says minister

Minister Darcy is clear the challenge remains huge. “We still have a long way to go,” she said in a mid-February interview. “I’m the first to say we have a long way to go.”

She also pointed out just how bad things were when the responsibility for the crisis became hers.

“We did inherit a system for mental health and addictions care that was not prepared to cope with regular needs of the population, much less a public health emergency, the worst one we’ve seen in decades in the province,” she said. “The overdose crisis certainly laid bare the cracks and the holes and the gaps in the system.”

Her job was to both fix that system and deal with the ongoing crisis, a challenge she regularly likens to flying a badly damaged airplane into a severe hurricane.

Two and a half years in, despite patches or improvements the government has made to the system, everyone agrees that the storm continues unabated.

Lance Stephenson, the director of patient care delivery with B.C. Emergency Health Services that manages the province’s ambulance service, said that the number of overdose calls had in fact gone up by two per cent with the agency responding to 24,000 such calls last year.

“While the death rate has gone down, the increase in calls have gone up,” he said. “I can only speculate that we’re doing a better job of saving lives of the people that are overdosing.”

Most of the deaths continue to be of people using alone, he said. “These calls come from all walks of life, from your neighbourhoods, from relatives, from friends. It’s not just about homelessness, it’s not just about mental health, it’s about drug abuse. It’s about abuse in the street and the drugs that we’re seeing in the field.”

Or as Kendall put it, “It’s a direct result of the toxic drug supply that continues to poison people.”

Among those who don’t die, there’s a high prevalence of brain injury due to the lack of oxygen reaching the brain between the time of overdose and when the person is revived. “We’re only just beginning to understand the full impact of this emergency and what the long-term effects will be on those who survive.”

In recent years there have been repeated calls to address the crisis by making the drug supply safer. In presenting the most recent statistics, coroner Lapointe noted the recommendation last year from provincial health officer Henry to decriminalize the possession of illegal drugs.

“We have the means to save their lives. What we have to demonstrate is the will,” Lapointe said.

Stressing that there’s no one solution, Henry said that while it would be ideal if the federal government were to take on decriminalization, the province has options too. In her report released last April, she identified options the province has under the Police Act including to set broad priorities for policing of people who use drugs.

“I’m not talking about legalization of drugs,” Henry said last week. “What we’re talking about is taking away that stigmatizing criminalization of an individual because they have a health issue, a dependence on drugs, and right now that drug supply is toxic.”

The stigma and the fear of being charged with a crime can keep people from seeking help, she said.

While expanding treatment and recovery are essential, the crisis is ultimately the result of the toxic drug supply, Kendall said. “We need to refocus on strategies to prevent overdoses from occurring in first place, however politically challenging that may be.”

That means a public health approach similar to alcohol or cannabis, where the supply is regulated and where there’s increased access to treatment and recovery, he said, adding there is a direct line from the war on drugs to the involvement of organized crime in providing the contaminated drug supply.

Pursuing decriminalization, as other countries have done, would be a move towards making that supply safer. That’s challenging for any government Kendall said, but even more so when there’s a minority government like B.C. now has.

“It seems to be a challenge that our elected officials are unwilling to take on at the present time,” he said. “I think a lot of the population are ahead of them in that area, particularly in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland.”

Speaking to reporters later that day, Darcy said the lives of the people who died mattered and that their deaths were a reminder of the family and friends who would be devastated and the front-line workers who would experience emotional turmoil that could last a lifetime. We’re only just beginning to understand the long-term impacts of the emergency, she added.

“We are working as fast as we can to fill the gaps in our system so that people will not continue to fall through the cracks,” she said. “We are not giving up. We are not slowing down. This is still a public health emergency, and our overdose response as a government will continue firing on all cylinders.”

That response has centred on the four proven pillars of prevention, enforcement, harm reduction, and treatment and recovery, she said.

“We’re making services more connected, we’re investing in early intervention for children and youth, we’re integrating mental health and substance use supports into primary health care, we now have rapid access to addiction services in every region,” she said.

“Our overdose emergency response centre is leading the charge as we continue to expand access to proven strategies, like take-home naloxone kits, overdose prevention services and greater access to treatment.”

Those interventions have averted some 5,000 deaths since the emergency began, she said, citing a figure from the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

The number of people receiving medication-assisted treatment, such as methadone or suboxone, is up 3,500 since the government took office. Some 300 people are receiving Injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment, a number the government intends to grow by 190 shortly.

And there’s more to come, Darcy said. “Very soon with our federal counterparts we’ll be announcing greater resources to scale up safer medication-assisted treatment for people most at risk of overdose.”

The provincial government has introduced regulations to improve the quality of care in supportive recovery homes, increased rapid access to addiction treatment, and expanded access to counselling for addictions and mental health, she said. More treatment beds have already opened and there are more coming this year.

There will soon be 19 Foundry centres across the province, building on the eight already open, aimed at getting support to youth early. Last June, Darcy’s ministry released A Pathway to Hope: A roadmap for making mental health and addictions care for people in British Columbia, a 33-page glossy booklet.

Recognizing that the crisis is disproportionately affecting Indigenous people, the government is working with the First Nations Health Authority and Indigenous communities to build two new urban treatment centres and to rebuild or renovate six more centres in rural B.C., an investment of $40 million, she said. The government has partnered with the health authority on overdose prevention projects in the 203 First Nations in the province.

The government is moving on all fronts at once, Darcy said. “There is no magic bullet. There is no single solution as Dr. Henry said. We need to expand all the tools in our toolbox.”

‘I haven’t seen anything change on the street’

A former ambulance attendant, Darren Gregory, says he’s struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and a substance use disorder for 25 years. He lives in Wynndel, near Creston in the Kootenays, and curates the Trauma Recovery Blog.

He’s complimentary about the effort Darcy has put in, saying, “She’s been working like a devil trying to get things done.”

The bureaucracy, however, hasn’t changed and there’s been no great influx of dollars into improving the system, he said.

“I haven’t seen anything that looks like magic from this new ministry,” he said. “I don’t see anything happening in the public system that’s productive and that’s going to turn the tide... I haven’t seen anything change on the street. Nothing.”

There’s good access to a mental health centre that Interior Health operates, but they don’t treat the trauma that underlies many people’s substance use, he said. “If you’re going to treat addictions you need to treat the trauma.”

There’s clearly a need to listen to people and keep doing what works for them, said Livingston of B.C. and Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, adding she has questions about how many people remain on injectable opioid therapy after a year, the expense of the Assertive Community Treatment teams, and the effectiveness of the Vancouver drug treatment court.

The province has spent money on those responses and has developed an industry around overdose prevention, but it has done little that would reduce exposure to the toxic illegal drug supply, Livingston said.

“Safe supply’s the thing,” she said. “If you have a safe supply, you don’t have to worry about people overdosing in their room at all.”

The ministry has become the face of fighting the overdose emergency, but it has an insignificant budget and no power to make policy, said Garth Mullins, the host and executive producer of the Crackdown podcast and a long-time opioid user who is now on methadone. “It’s creating the perception, the Potemkin village, of an emergency response, but it’s not an emergency response.”

In the province’s annual budget released in February, the ministry received less than $10 million, making it smaller than even the premier’s office and a rounding error on the main health ministry’s $22.2-billion budget.

There’s no across government co-ordination on the overdose emergency, and the ministry creates another layer between advocates and the people who actually make the decisions, Mullins said.

He drew a contrast with the international response to COVID-19, the coronavirus outbreak that has dominated headlines as public health officials have rapidly mobilized to prevent its spread. “That’s what an emergency health response looks like.”

The province’s representative for children and youth, Jennifer Charlesworth, said there have been positive steps, like putting prevention programs into the school system and expanding the Foundry centres, but not nearly enough.

“We’ve been looking for more robust investments in mental health and addictions for kids that are [using]... you know prevention is great, but there are kids that are using that are extremely vulnerable that have complex needs and so we’re not seeing that kind of investment,” she said.

Charlesworth said it’s been up to her office to research what addiction and substance use services are available for children and youth, work that could have been done by the ministry. “It’s hard to measure change if you don’t have a baseline, so hopefully now we’ve established the baseline of what is available in the province, but that was a lot of work we had to do.”

The representative’s office sees a few hundred critical injury reports a month and many of them are for people between the ages of 14 and 18 who are dealing with overdoses and everything associated with that, she said, including youth losing their housing, being sexually exploited or struggling with mental health issues. Nor does the residential care system handle harm reduction well, she added.

“It’s messy, and we can’t shy away from those kids who don’t fit neatly into a box,” Charlesworth said. Her office would have liked to see more progress in two and a half years, she said. “There’s some good things for sure, but we’re most concerned about those who are just so vulnerable and they’re falling between the cracks.”

‘The overdoses have not gone down’

The BC Liberal opposition critic on mental health and addictions, Jane Thornthwaite, said she supports the idea of having a separate ministry responsible and that the government has taken some positive steps, but she questions whether it’s effective enough to justify the expense.

“The main point is it is a ministry that does not offer services,” she said. “I support the idea of a separate ministry because I want somebody responsible 100 per cent on mental health and addiction, as opposed to kind of on the side of somebody’s desk in health.”

Started under the former BC Liberal government, the Foundry centres in particular are good, and it’s great that the government is expanding them, she said.

However, Thornthwaite said, her support for the ministry has to be balanced against what else could be done with $10 million dedicated to mental health and addictions. “I think what you have to look at is what is the result of that ministry,” she said.

It’s not clear that the issue is a priority for the government, she said, speaking the day after the province’s finance minister released the annual budget. “I don’t think Carole James said the word ‘opioid crisis.’ I didn’t hear it, and that really disturbs me.”

The closest James came in that speech was to say, “Soon every post-secondary student will have access, 24-7, to mental health support services. This builds on a province-wide expansion of Foundry centres to provide youth and families with a one-stop shop for mental health and substance use supports, because we know it’s crucial to reach out to people early, before challenges escalate.”

It’s not clear that the ministry is succeeding in its mandate, Thornthwaite said, noting that people are still overdosing at the same rate.

“The overdoses have not gone down, which means we’re not getting to the root of the addiction,” she said. “We’re not getting to mental health, we’re not getting to trauma, we’re not getting to childhood trauma, pain... and people aren’t getting the help they need to get off the drugs, even if they want to get off the drugs.”

She said she’s spoken to countless youth and adults who want to get into detox, but it isn’t available when they’re ready to go. “Or they get into detox and the next stage of the recovery is treatment, there’s a gap, so they have to go back where they came from, they go back to the environment of where their addiction started. This is a constant problem. This ministry has not helped that. The gaps are still there and I’m disappointed about that.”

The government has done an excellent job on harm reduction, which keeps people alive, but has fallen short on treatment and recovery, she said.

“The harm reduction is not the end, it’s the transition,” she said. “There doesn’t seem to be the concerted priority to get people well.... Once we’ve got them stabilized, let’s work on getting them well.”

Thornthwaite also said the government lacks an addictions strategy, and she was dismissive of the Pathway to Hope document. “There’s no checks and balances, no accountability. It’s just ‘we want to do this’ and half the stuff was already underway anyway.”

‘Decriminalization is a federal issue’

Darcy said that while her ministry doesn’t directly deliver services, it is leading the response to the overdose crisis and working in partnerships to build a better system for mental health and addictions care.

“A conscious decision was made at the beginning when the ministry was created, to not transfer all the services, to reorganize health care once again. It’s been done many times,” she said. “There’s no evidence it results in better outcomes for patients, but it takes a lot of time and a lot of money is spent on reorganization.

“We made a deliberate decision that our ministry would develop the strategy and the action plan and work in partnership with other ministries in order to drive it,” she said.

Her ministry’s budget may be small, but the government has invested $600 million over five years to respond to the crisis.

“We knew from the beginning that there wasn’t one simple solution,” Darcy said. “We’ve said we need many tools in the toolbox, because addiction has many and complicated roots and because every patient’s journey is different, and so we need a wide range of options for people.”

The ministry works closely with the health ministry, but also on various initiatives with the ministries of advanced education, children and family development and education. Darcy chairs a cabinet mental health and addiction working group that includes the ministers of health, housing, social development and poverty reduction, and children and families.

“We do work across government,” Darcy said. “When we develop these plans and we bring proposals forward to [the] treasury board that are included in budgets, that really is about us having done that collaboratively and it’s decided by government as a whole.”

On decriminalization, Darcy said the province is doing what it can within the federal laws, yet she declined to say to what degree the province has pressed Justin Trudeau’s government on it. “It’s been the subject of numerous conversations. I’ll just leave it at that.”

Solicitor General Mike Farnworth also insists decriminalization would be up to the federal government and avoided saying whether the province would like to see a change.

“We’ve made it clear that it is a federal jurisdiction and the feds are the ones that would have to move on it,” he said. “Decriminalization is a federal issue. We’ve been moving ahead on things that are under provincial jurisdiction.”

As for safe supply, on that as well the provincial government is doing what it can within federal rules to offer safe prescription alternatives within a medical model, Darcy said. “To me and to our government, safe supply is about increased access to safe prescription alternatives to the poison drug supply on the street and that’s what we’re doing.”

There are new initiatives coming all the time on the overdose emergency, Darcy said. “Nobody’s claiming victory by a long, long shot. We have a long way to go on turning the tide on what’s a terrible crisis, and we’re not taking our foot of the gas.”

Horgan, who campaigned in 2017 on setting up the ministry, said he believes it is doing what he intended.

“It was always more than political appeal,” he said. “It was to ensure there was someone at the executive council table that was getting up every day concerned not just about addictions, not just about overdoses, but also about ensuring that we’re delivering mental health services in a way that people in the 21st century would expect us to do so.”

Awareness of the impacts of mental health issues are higher than ever and it’s appropriate to have a minister making sure they remain at the forefront, said Horgan. “I believe Judy Darcy and the ministry that’s been constructed since 2017 have been doing great work on ensuring we’re delivering services in communities that are helping people.”

Some of the next steps will require co-operation from the federal government, he said.

The number of people dying may have ebbed, Horgan said, but it remains too high and the provincial government is committed to doing more. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Federal Politics, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: