The Trudeau government just ordered the CRTC to ensure it will better “promote competition, affordability, consumer interests and innovation” in Canada’s telecom industry. Earlier this month, the B.C. government made a throne speech pledge to tackle high cell phone bills.

If politicians are getting the message that Canadian voters are fed up with high cellular bills, it’s because they pay the worst rates for mobile services in the developed world, as yet another recent study confirmed.

It wasn’t even close. Canada landed dead last by a long shot when researchers compared how much mobile data $45 can buy.

If Canadians want a proven path to lowering our sky-high cellphone bills and boosting competition, we should acquaint ourselves with the example of Israel. In that country a government minister made cellular price gouging his crusade. By the time he was done an oligopoly had been shattered, users’ bills had dropped by two-thirds or more, and the economy barely missed a beat.

The story begins in 2009, when a Likud party politician named Moshe Kahlon was reelected to the Knesset and appointed minister of communications.

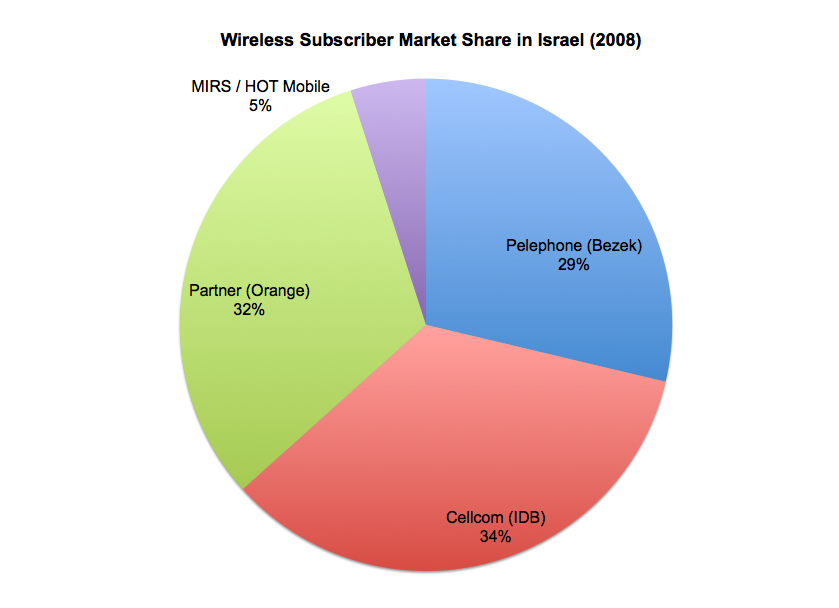

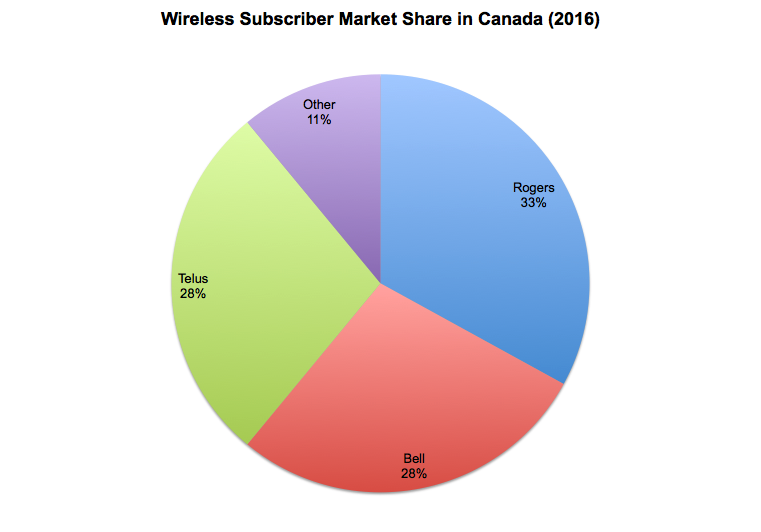

At the time, Israelis were also paying high prices for cellphone service compared to countries in the OECD. Commanding those rates were Israel’s “big three”: Pelephone, Cellcom and Orange (now called Partner). Canadians take note: Our cellular market is dominated by a big three too: Bell, Rogers and Telus.

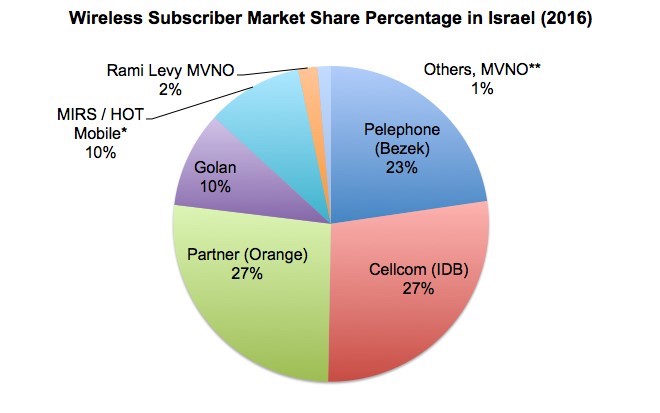

As minister, Kahlon pushed through reforms that made it easier for upstart competitors to take on Israel’s cellular oligopoly. (These policy changes are explained in some detail in the second half of this story under the sub-headline: How Israel chopped cell phone bills.) As new companies tried to steal away customers, the big three were forced to woo them to remain by offering new deals.

By 2011, typical plan prices had spiraled downward by 60 to 80 per cent. Plans that formerly ranged between 150-250 Shekels ($55 to $90 Canadian) reached rates as low as 29 to 99 Shekels a month ($10 to $35 Canadian). And they stayed there.

These weren’t the kinds of bare bones, data-only plans the Canadian government recently ordered our big three to offer in the name of providing affordability.

Israelis have their pick of various all-you-can-eat data and airtime plans at prices inconceivable in Canada today.

In this country, meanwhile, those ultra-basic data-only plans start at three times what the plans cost in Israel at $10.

Kahlon’s reforms, within three years, had saved consumers an estimated $6 billion (CDN) on their cell phone bills.

In Canada since 2009, by comparison, prices for desirable phone plans and market share among big players have remained among the highest in the world.

But of course any politician would be a fool to defy an oligopoly and the political might it wields, right? Not true for Moshe Kahlon. His reforms made him such a hero he started and leads his own political party, Kulanu, a member of Israel’s current coalition government.

“When Mr. Kahlon came into office he didn’t want to be a minister of communication,” said Amir Teig, a journalist who covered Kahlon for the Israeli business newspaper The Marker. The communication ministry was “third-tier” with low visibility, he told The Tyee.

Kahlon could have made friends with the big players in the mobile industry by turning a blind eye. Instead he took a very close look at them, and he didn’t like what he saw.

“It was a very concentrated market. The margins were some of the highest in the world. They paid huge dividends to highly leveraged stockholders,” said Teig. “You don’t have to be a professor in economics to see that this market had a huge problem. Prices were the high end of the prices in the OECD and profits were huge.”

Kahlon noted the cellular industry accounted for nearly five per cent of the GDP with very strong profit margins topping out at 40 per cent (as measured by EBITDA — earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization).

What struck Kahlon as out of whack in Israel remains the norm here in Canada. Our mobile sector has had even higher profit rates, averaging 45 per cent in 2015. The telecommunication sector as a whole in Canada was worth $48.7 billion a year and rising by 2016, representing about 2.4 per cent of the GDP.

After Kahlon’s reforms took hold, the bottom lines of Israel’s big three felt the shock. But the firms stabilized and, in the newly competitive market, reported EBITDA margins of about 10 points less on average.

Revolutionary lessons

What can Israel’s “cellular revolution” (as it’s now known) teach us in Canada?

Israeli governments had previously campaigned on reforms but had not succeeded in effecting much change. Then came Kahlon, “someone who remained connected to his modest roots, and was well-connected to the community,” Harvard Business School professor Joshua Margolis told The Tyee.

“He is a humble person who wants to do things that will benefit the general population — not in some grandiose demagogic way but rather in a way that can help the daily lives of people who were often neglected. He stayed connected to that so even when he had power as a minister it was important to him.”

Margolis specializes in business cases where leaders have faced strong headwinds and potential personal cost while making important decisions that advance a greater good.

Margolis has made a close study of Kahlon and Israel’s cellular revolution because, he said, “A number of other people had been in his position and shoes before and had blinked. He did not.”

Kahlon faced down the influence the big three wielded in the media and government. They could afford to pay lobbyists and buy advertising in all of the largest publications.

As his measures were scheduled to take effect, Kahlon fended off others in the government who asked him to back down and ignored attacks in the press. His own daughter once asked him if it was true he had declared personal bankruptcy as she had heard falsely reported on the television, according the case study Margolis wrote for the Harvard Business School.

“They will write whatever the companies that pay them for ads ask them to,” said journalist Teig of Israel’s larger media companies. One of the big three telecom players made moves to buy outright control of a major newspaper right as the reforms hit, according to Teig.

In Canada, the cellular industry has significant overlap with large media ownership. When cellular high prices get coverage, even in the public broadcaster CBC, telecom industry group talking points usually get prominent treatment.

Those talking points tend to be that Canada is a big country with sparse populations in many areas, so cellular customers are paying for investment in necessary infrastructure built by the big players. "We're paying for a Lexus, but it's worth a Lexus," is how the author of one conservative think tank report put it.

But critics point out not everyone can afford a Lexus, and, as a 2017 report commissioned by the federal government noted, Australia manages to have much cheaper cell phone service despite its vast, lightly settled areas.

Perhaps, then, as Harvard’s Margolis argues, the missing factor in Canada is political courage.

Kahlon’s boldness was bolstered by soured public perception of big telcos, and recent events in Israel. “There was a convergence of factors. You had someone like Kahlon that cared about it, and who was able to listen to arguments on both sides. You had some of the press which were mobilizing and willing to create cover on calls for reform,” said Margolis.

The reforms also coincided with Israel’s equivalent of an “Occupy Wall Street” movement triggered by high dairy prices. All of this added up to create a more receptive public, said Margolis.

Leading the pro-reform media coverage was the paper employing Amir Teig. The Marker is a popular center-left business print daily. At the time, Kahlon was part of the right-wing Likud party. “When I met Kahlon the first time,” said Teig, “we were laughing and he said, whatever he does, we as a leftish media group are not going to support him.”

Teig assured Kahlon he and his paper would cover reforms on the industry fairly. Teig later learned that his editor in chief said the same thing to Kahlon.

How Israel chopped cell phone bills

Kahlon’s approach, put simply, was to set up conditions in the marketplace that would aggressively incentivize fast market capture for new entrants, and to take aim at every practice in place that made it prohibitive for customers to switch between companies.

This meant he had to counter industry lobbyist arguments. He insisted, for example, that the companies — and Israel’s job market — were strong enough to weather the transition, Margolis explains in his case study. Indeed, the fallout of price wars caused the big three companies to shed thousands of jobs. But because the industry has a high turnover rate, this largely meant simply not rehiring.

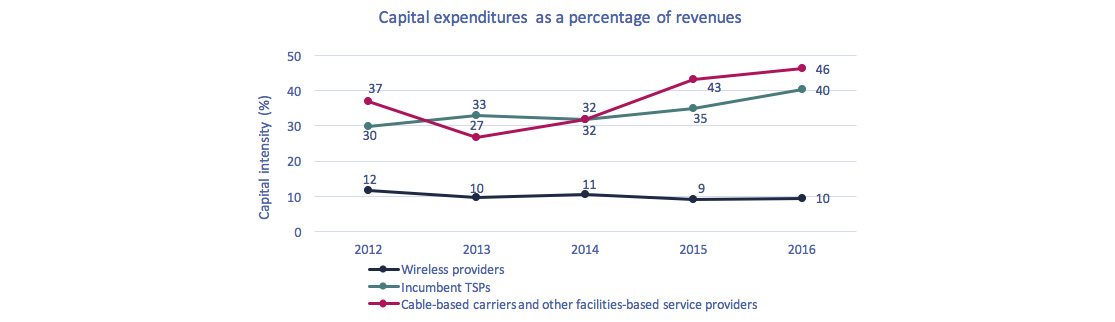

There were warnings and predictions of doom for the economy. Cell phone service companies were reliable sources of cash flow for larger companies that owned them and their dividend-earning investors. Companies threatened they would cease investing in infrastructure — a familiar warning from the big three to Canadian regulators when considering measures to increase competition.

But Kahlon persevered. And in fact, after reducing infrastructure investment the first year, the companies ramped it back up.

In 2014, the third year after the reforms took effect, Israel’s mobile sector spent the equivalent of 13 per cent of revenues on expanding infrastructure. This was higher than for Canada’s wireless industry, which has invested between 10 and 12 per cent in recent years.

Phone and service decoupling

Kahlon de-coupled monthly payments for the actual phones from service agreements. This meant that if a customer was unhappy with service or saw a better deal after pledging to pay down a new handset for two years, they could simply cancel their service plan and switch to a new company, while continuing to pay the original company the separated phone payments only.

In Canada, a customer would have to pay out any still-owing amount on their phone purchase price and part ways with the company entirely before leaving their rate plans, per their contracts. Therefore, they are likely to stick with their provider a full two-years — the government maximum term length set in 2013. When this locking-in was permitted in Israel, 90 per cent of customers would bear out their plans until the end, Kahlon pointed out, stifling competition.

This freeing of phone purchase payments from service agreements also, very significantly, curbed the tendency for companies to have exclusive agreements with hot handsets manufacturers like Apple, a major driver of consumer choice.

License tendering using long-range thinking

Kahlon anticipated issuing two new wireless licenses to firms aiming to compete with the big three companies, but wanted them to have a fighting chance. He aimed to ensure the new companies captured a meaningful share of the market on a set timeline. To accomplish this, Kahlon used a twist on one of the key tools governments have in bringing in mobile competition: issuing licences to use a newly available wireless spectrum.

Periodically, new spectrums of radio frequencies are made available to the cellular industry. The manner in which they are given out can have profound effects on the competitive landscape. Governments frequently award them to the highest bidders due to the massive boost the auctions can provide to national coffers.

Kahlon instead decided to set up a different scheme. He offered to completely repay the new cellular companies’ expensive license bids — essentially giving away the valuable spectrum — provided they reach market capture and tower coverage thresholds at set intervals.

The terms required capturing seven per cent of the markets within five years, and ensuring coverage of 90 per cent of the country within seven years. The coverage requirements were done with gradual threshold increases each year, and the license rebates were offered at one-seventh of the fee for each one per cent of market capture.

Two bid winners — Golan and Hot mobile — met those thresholds and became viable competitors, going on to capture a combined 20 per cent of the market at two million subscribers.

The government effectively sacrificed about $1.4 billion Shekels ($504 million Canadian) in license fees per the companies bids, to support the scheme that contributed to over 10 times as many dollars saved by Israeli households within five years.

Virtual operators

Kahlon greatly lowered roaming rates that the big three must offer to new entrants and forced them to lease their networks (at set rates that still produced profits) to MVNOs, “virtual operators” who have no physical infrastructure. He again ignored cries from the industry that this was unfair and would kill any incentive to continue investing in infrastructure — claims which proved untrue.

Kahlon touted the low rates that could be offered by these firms who needn’t recover infrastructure costs as a key part of the plan to effect change.

Several MVNOs became viable competitors. The only one reporting its numbers is Rami Levy at 200,000 subscribers or about two per cent of the market.

Meanwhile, back in Canada

Canada’s spectrum auctions during the period of Israel’s reforms and since primarily favoured accepting the highest bidders, earning typical short-term windfalls of millions or billions for government coffers on each occasion (a recent 2015 auction produced $58.5 million, another in 2014 produced $5.3 billion) but with some spectrum reserved for smaller companies.

While opening several new wireless frequencies over the years since 2008, Canada has required no commitments or incentives for any winners of the reserved spectrum to capture any specific market share or provide a specific area with coverage nor any measure that would seem to indicate the government is serious in ensuring new companies’ viability as competitors.

Canada’s regulators during this time have set a still-elusive goal of adding a “fourth competitor” in each of its provinces’ markets. The regulators’ method has been to set aside 40 per cent of the auctioned new spectrum for bidders that have less than 10 per cent of the market share.

The deep-pocketed big three predictably gobble up the remaining 60 per cent of the spectrum. And within years of said auctions they have a tendency to gobble up the new entrants, too. In one recent case they simply bought an entrant company’s still unused spectrum, sold to the big three buyer at a huge profit from the bidding price. Unlike in Israel where mergers have been blocked, the Competition Bureau in Canada allowed smaller companies that won auctions to sell out to the big three after a mere five-year legislated wait.

In March, the federal government will apparently take the same approach to auctions when it sells off the 600mhz spectrum

What about Israel’s approach allowing independent virtual operators (MNVOs) who do not have their own network towers to lease their network from large operators? The CRTC, as led by both Harper and Trudeau-appointed heads, has thus far accepted the industry argument that investment in infrastructure will be stifled if this is allowed.

Minister of Innovation Navdeep Bains did ask the CRTC to look for a second time at its most recent decision shutting down “Wifi First” MVNOs that use the big three’s infrastructure.

A reversal of the original decision would have enabled virtual operators to enter the market, as in Israel where they are viable competitors. But Trudeau’s CRTC, headed by a former Telus executive and telecom lobbyist, simply reaffirmed the decision to block the companies.

Another barrier for new entrants in Canada has been the inability to secure deals for the hottest phones that are critical to competition. This difficulty is by design due to deals for exclusivity aggressively pursued and enforced by the big three. They understand that access to a new discounted iPhone or Galaxy will dictate a choice in service providers for a large portion of consumers.

To overcome this barrier, Wind Mobile found a way to secure older iPhones from a vendor that refurbished them. But Apple forced the vendor to cut their supply off, after receiving pressure from big three vendors with whom it has had agreements.

Wind Mobile changed its name to Freedom mobile, which is now backed by western Canada television cable giant Shaw and occupies a distant fourth place in the market. Freedom has managed to obtain agreements with Apple.

Hot (again) file: telecom

This week’s federal government directive to the CRTC to act to make the cell phone industry more competitive has the ring of déjà vu. When the Trudeau government took power three years ago it made similar noises.

After Trudeau appointed Bains minister of innovation, the first item in Bains’ ministerial briefing under “priorities and hot files” was “Telecommunications Competition and Access.”

Found in Bains’ mandate letter from Trudeau is a now nearly four-year-old phrase that resembles the order given this week to the CRTC. Trudeau back then directed Bains to “increase high-speed broadband coverage and work to support competition, choice and availability of services, and foster a strong investment environment for telecommunications services to keep Canada at the leading edge of the digital economy.”

If Trudeau and his government are serious this time about making that happen in the cellular sector, perhaps a field trip to Israel is in order. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: