An agreement to close salmon farms in the Broughton Archipelago is a tentative step in the right direction, say industry critics.

But both industry and government “have a long way to go to really protect wild salmon,” says Alexandra Morton, a biologist and vocal critic of the foreign-owned fish farm industry.

After months of negotiation, the province and the ‘Namgis, Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis and Mamalilikulla First Nations announced an agreement to remove some fish farms in the Broughton Archipelago on northern Vancouver Island’s east coast. The plan, announced Friday, also gives First Nations more control over the monitoring of fish diseases.

Both Marine Harvest, a Norwegian firm, and Cermaq, a Norwegian-run subsidiary of Mitsubishi, have agreed to the plan and foresee no impact on jobs.

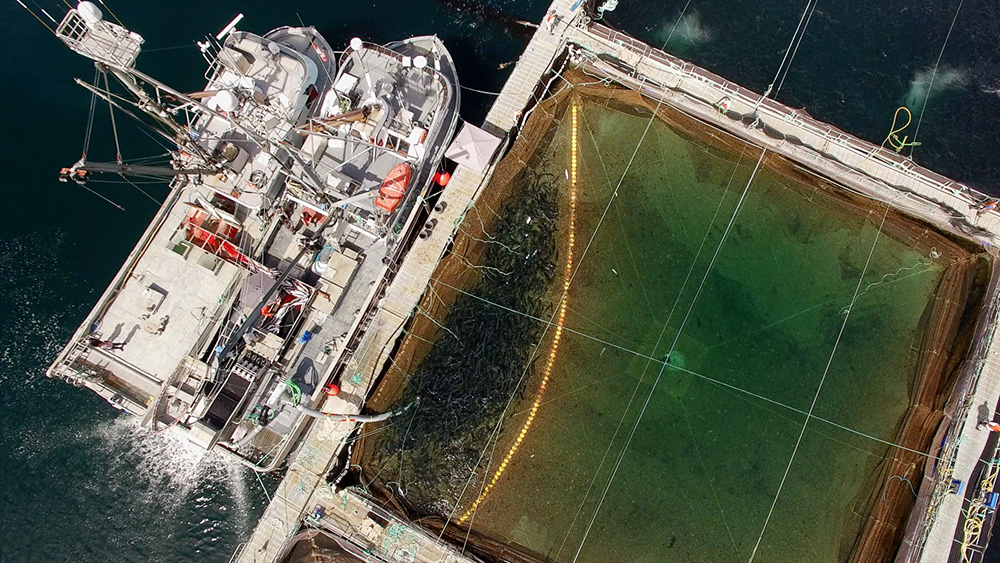

The companies currently operate 20 industrial open-net facilities in the Broughton producing Atlantic salmon for export markets. Not all are affected by the agreement.

The plan will see four farms close next year, two in 2020, one in 2021 and three in 2022.

Seven farms have the potential to continue operating if companies secure agreements with First Nations agreements and DFO licences.

But Morton said the government numbers are misleading. The agreement says four open-net Atlantic salmon feedlots will close in 2019.

“Yet three of those farms are fallow or haven’t been operating for years,” Morton said.

The only active facility that will close next year is Marine Harvest’s Glacier Falls farm — but its fish will move to other facilities, Morton said.

She said she’s been watching wild fish migrate out of the Ahta River near the farm for decades and has documented a substantial decline. “I look forward to seeing to fat and happy young salmon there next spring,” Morton said.

Still, with the planned closure of Cermaq’s Burwood facility and Marine Harvest’s Wicklow feedlot, Morton calculates that three key salmon rivers in the Broughton might be protected within three years.

“After that the picture gets cloudy and I’m not sure how many farms will be removed after that,” said Morton.

The agreement follows years of scientific debates and sustained Indigenous protests over salmon farms due to viral disease risks, the proliferation of sea lice and the colonial occupation of aboriginal territories.

A growing number of groups, including the BC Union of Municipalities and the Pacific Salmon Foundation, have asked that the industry move to closed containment systems to protect dwindling populations of wild salmon and their migration routes.

Ernest Alfred, a Namgis hereditary chief who participated in a 280-day occupation of a Marine Harvest farm, called it an historic day because “the industry has taken a big step back” and said he is optimistic about its implementation.

But many First Nations “are not excited about the timelines and how many years they are going to drag out this process,” he added.

The new agreement also calls for the creation of a unique Indigenous monitoring and inspection plan to oversee fish farm operations during the phase-out. The plan would give First Nations authority to monitor and test hatchery fish for pathogens before they are transferred to open-net feedlots.

Morton and the Namgis First Nation have launched separate lawsuits challenging the DFO’s decision to allow the companies to place fish with piscine reovirus (PRV), which can cause a deadly heart disease in salmon, in open net ocean pens.

Morton’s lawsuit alleges the DFO isn’t abiding by a 2015 Federal Court ruling that found it was failing to fulfill its responsibility to ensure fish introduced into the ocean were not carrying disease.

About 80 per cent of all farmed fish now carry the contagious piscine reovirus. The virus is a major killer on fish farms in Norway and, more recently, British Columbia.

In Norway, home of the Atlantic salmon industry, production has stagnated since 2012 due to sea lice plagues, stricter regulations protecting wild fish and growing coastal concerns about the industry’s impacts.

As a result Norwegian companies are pursuing closed systems in the fjords or open pens further offshore.

Last month the northern city of Tromso created a furor when it voted to ban any more fish farm licences in its territory. It also said “existing farming operations should not be expanded unless they are within closed, land-based facilities,” said one news report.

Earlier this month the Canadian federal government, a long-term booster of the fish farm industry, said it would look at new ways of doing business including a study on land-and sea-based closed containment pens and a move to “area-based approach” to management to ensure fish farms are not affecting wild salmon migration routes.

The federal government, which has a dual mandate to protect wild fish and promote aquaculture, also said it would uphold the “precautionary principle” to ensure what it called “sustainable management of aquaculture.”

But critics say the so-called new approach may just be a repackaging of the old approach, which emphasized industrial “growth” at the expense of wild fish stocks.

Will the federal government, which oversees the industry, actually respect the results of independent aboriginal testing and monitoring on fish disease? Morton asks.

Earlier this year Julie Gelfand, the federal commissioner of the environment and sustainable development, concluded the DFO wasn’t protecting wild salmon.

Gelfand found that “Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not adequately manage the risks associated with salmon aquaculture consistent with its mandate to protect wild fish.”

Marine Harvest Canada says in a news release that it doesn’t plan to decrease production because it will shift operations to other parts of the coast.

The company said it would seek to gain to “a number of licence and tenure amendments to shift production from sites that will be decommissioned to other sites.” Marine Harvest also said it plans to seek new salmon farming sites “where there is First Nations’ interest and consent.”

Morton said such plans mean the disease and sea lice burdens posed by industrial fish farming will simply move to other coastal waters on Vancouver Island.

Alfred said other First Nations would have to assess how this affects them. “Our neighbours will have to consider what they are now putting at risk,” he said.

He suspects that the expansion in other areas will increase the pressure on the Fraser River salmon run.

“It is going to take every nation along the Fraser River and the coast to start working together and say we want a clear path for our wild salmon in the ocean.”

The new agreement also does not include some of the fiercest critics of B.C.’s fish farms.

After fighting government for more than 30 years over fish farms, the Dzawada’enuxw First Nation launched a lawsuit earlier this year against the province, the federal government and two companies.

It claims that fish farm licences were granted in its territory without its consent and that “there is a serious issue regarding the constitutionality and legality of tenures issued under the Lands Act.”

The Dzawada’enuxw, whose territory includes Kingcome Inlet, are also seeking a court injunction that would prevent Marine Harvest and Cermaq from seeking renewals of their provincial licences in their territory.

Morton, who has documented the industry’s impacts on wild fish for 20 years, said despite is flaws the new agreement still represents a significant shift.

“The First Nations forced the government to do something and said get the fish farms out of the Broughton, but with this agreement the government has finally shown some respect. But the fight is not over.”

She added that wild salmon in the Broughton are still in critical condition.

“The next rung on the ladder is extinction.” ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: