[Editor’s note: This is one of a series of articles drawn from 'All Together Healthy: A Canadian Wellness Revolution,' written by Tyee legislative bureau chief Andrew MacLeod and just published by Douglas & McIntyre, that challenges assumptions about how best to improve health for Canadians.]

In a March 2017 report British Columbia’s Auditor General Carol Bellringer called attention to the ever-rising health care budget. Per person, the B.C. government spent $4,050 in 2016, which was slightly below the Canadian average. In a conference call with reporters, Bellringer said that the lower spending could be the result of a healthier population compared to other parts of the country, but that it could also be the result of fewer services being offered.

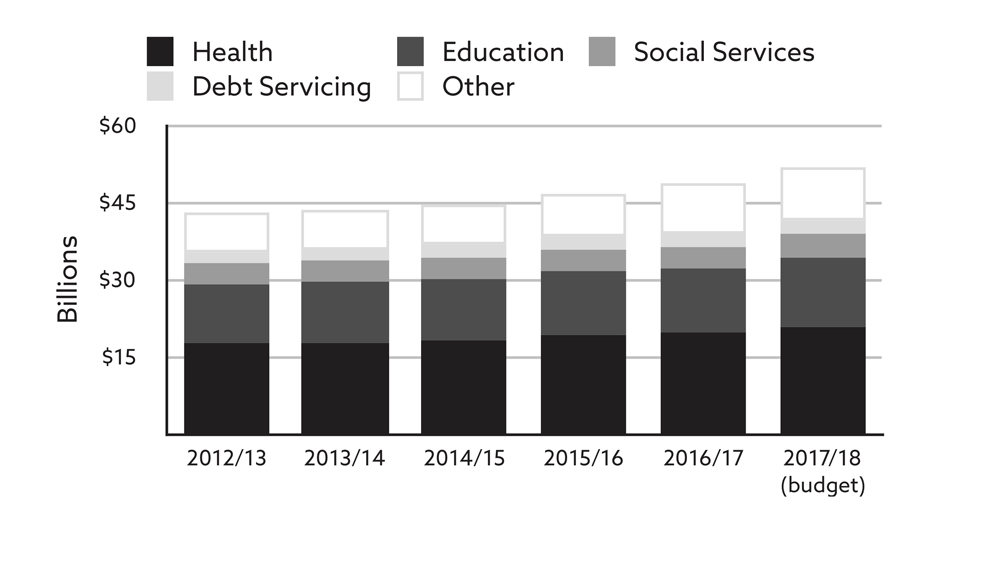

Still, health remained by far the largest draw on B.C.’s budget. The spending on health was already three times more than on education, the next largest ministry. And the increase the ministry was forecast to receive over a five-year period was equivalent to the entire budget of social development and social innovation, the third largest ministry. It was also equal to the money to be spent on the 11 smallest ministries.

Within the health ministry’s budget, some areas soaked up more spending than others. Since 2012, the amount spent on in-home nursing care had risen 14 per cent. An extra five per cent went to group homes for people with disabilities and residential care for seniors. Acute care — which includes emergency, post-surgical and critical-care services — was up 11 per cent. The increase for services to help with mental health and substance use saw a smaller increase, just three per cent.

Meanwhile, tellingly, public health programs aimed at prevention, screening and controlling communicable diseases actually saw a decrease. For those programs, the budget was cut back by a percentage point.

“The health sector has the greatest spending pressure in all of government,” Bellringer said. “While one-and-a-half per cent here and three per cent there may not seem like a notable difference, a one per cent change to a major health program could be representing millions of dollars.”

I asked Bellringer how much sense it made to cut spending on prevention programs when they might offer a way to contain rising costs.

She responded, “In terms of how much should be budgeted for an area, we leave that to the politicians. It’s a policy call and it’s actually something we’re not permitted to comment on.”

But without telling them what to do, would more commitment to prevention not be a logical way to contain costs?

“As a logical answer to that, of course, yes it would,” she said.

If politicians are looking for cuts in other health spending to put into prevention, drug spending is a prime place to seek savings.

New drugs, particularly for “orphan diseases” that affect relatively few people, can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. While the evidence on whether or not they work can be mixed, there’s often a push from those that feel they benefit to have them covered.

Lilia Zaharieva, for example, a 30-year-old in Victoria, received sympathetic media coverage as she sought to have the public PharmaCare plan pay for Orkambi, a drug for cystic fibrosis that Vertex Pharmaceuticals makes and sells for about $250,000 a year. “It’s very painful to think about what it would be like to lose Orkambi,” she was quoted saying.

She had received funding for the drug through the insurance plan available to students at her university, but that was ending. “The feeling of watching these magical pink pills dwindle away every time I take them is both terrifying and yet a call to action.”

The local paper characterized it as a “life-or-death fight” that could result in lung failure or the need for a transplant if unsuccessful.

It was left to B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix to explain that despite the “very serious situation,” both Canada’s Common Drug Review and the Drug Benefit Council had advised against funding the drug since they lacked evidence of its therapeutic benefits.

That hardly ended the issue. In July, after the book from which this piece is drawn was published, Zaharieva became a lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against the B.C. government, the federal government and the two bodies who, the suit charges, were “flawed” in their decisions against coverage for Orkambi. Zaharieva, who for now receives Orkambi for free from its maker Vertex on compassionate grounds, claims her Charter Rights have been violated. The lawsuit seeks damages of $60 million. “I see this step as an unfortunate last resort,” she declared before microphones and cameras at a news conference.

It was a dramatic reminder that any politician defending such a decision, even when seeking to take a responsible stance, risks appearing cold-hearted. And politicians face similar pressure across a wide range of diseases, often from patients’ groups with strong ties to the drug industry.

The forgotten success story

As University of Victoria biomedical ethics professor Eike-Henner Kluge put it, “Clear thinking tells us that funding untried or unverified health care — health care that has not been shown to be more effective than other types of treatment (or no treatment at all) — is to fund on the basis of hope. Which is fine, when resources are unlimited.” If resources are limited, then giving them to one person and not another needs to be justified, he wrote. “One should ask oneself... whether the particular individual for whom one is pleading is any more special than those others with whom one is not acquainted and of whose plight one is not aware.”

With limited public funds available, there is a choice to be made between paying for an expensive, unproven drug, providing a family with housing, or raising ten families above the poverty line.

The public discussions about drugs like Orkambi don’t tend to take into account what else the money might be spent on.

A better approach would begin with recognizing the underlying causes of the majority of illnesses and proactively addressing them. Norman Temple is a nutrition professor at Athabasca University. He has observed that the key determinant of most of the major diseases afflicting Western societies is lifestyle. Cancer and heart disease have much more to do with smoking and diet, which are both closely tied to income, than they do with the care that’s available.

As Temple put it, “There is now very little debate that most of the diseases that afflict our society are preventable. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of these medical findings, for they hold the key to effective action for disease prevention at the level of both the individual and the population.”

Prevention would in the long run be much cheaper than the current approach, Temple argued. “By its very nature, prevention is ‘low-tech’ and should therefore come with a modest price tag. Potentially, far more can be accomplished with far less resources than is typically the case with new ‘high-tech’ treatments.”

It’s also better for the patient to avoid being sick in the first place. “Even when an effective treatment for a particular disease is available, it is obviously far better if we can prevent that disease, or at least postpone it until later in life.”

There are many examples of prevention’s past triumphs. Temple pointed to the success over the past 150 years fighting infectious diseases. “What is often forgotten is that primary prevention was the driving force behind this great success story,” he wrote. “In particular, the widespread adoption of hygiene, after the importance of this was discovered, played a major role. Actual medical treatment, such as the development and use of antibiotics, played a fairly minor role.”

Temple was not, however, calling for a renewed commitment to pestering the population to make better choices. As noted in the first article in this series of Tyee excerpts from my book All Together Healthy, deeper forces underlie the choices that individuals make.

Temple argued that governments are in a position to prompt healthy behaviour in ways that go far beyond telling people to eat their vegetables. “Governments have the power to pass legislation and to manipulate prices using taxation and subsidies. These government powers have tremendous potential for influencing health behavior.”

Governments could also do more to set the conditions that would give more people the capacity to make better choices. In his 2012 book on the Canadian health care system, Chronic Condition, Jeffrey Simpson pointed out the need to combine health promotion with broader social supports.

“If governments and their citizens were truly serious about health promotion, they would confront the social determinants of health, which would include employment and working conditions, housing, standards of living, early child development,” Simpson wrote. Efforts to promote healthier living and prevent illness have achieved little success because governments avoid acting on the link between the social determinants of health and health outcomes. “It is easier, and less costly, to develop health-promotion programs and to pursue a wellness agenda than to tackle entrenched income inequalities.”

A $6.2-billion opportunity

The Public Health Agency of Canada put a price tag on health inequity in an April 2016 report. It used Statistics Canada data for 2007–2008 and looked at services that make up about a quarter of health care provided in the country. As a person’s income rises, both for men and women, the amount it costs to provide health care to them declines.

“For the services included in this report, socio-economic health inequalities cost Canada’s health care system at least $6.2 billion annually,” the authors found. “This represents over 14 per cent of total spending on acute care in-patient hospitalizations, prescription medications and physician consultations.”

In that inequity, however, the authors saw an opportunity. “There is potential to reduce these costs if all Canadians could match the health care usage patterns of the highest income group,” they wrote.

The biggest gains were to be found by improving the health of the people at the bottom of the income scale, the report said. Within the management of health care, governments have a role as gatekeepers, making sure the public pays for what works and avoids wasting money on what doesn’t. In doing so, more budget room would be created for needed action outside of the health care system, action with the potential to help many more people be healthier.

Part four: This series wraps up with a look at Canada’s opioid crisis, and the siren it sounds for our society. Find the entire series here. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: