Facebook’s response to the Cambridge Analytica scandal has made much of the claim a harvest of user data reaching beyond what each user authorizes to an app couldn’t happen today.

The corporation says the loophole exploited by a Cambridge professor and other app developers to vacuum up vast amounts of personal data on Facebook users and their “friends” was closed in 2015.

But a Tyee investigation identified three current vulnerabilities that make it easy for app developers to gather data on the Facebook friends of someone who downloads a quiz or game — the tactic used to collect information on millions of people for Cambridge Analytica.

Update: Facebook quietly closed the remaining vulnerabilities on April. 4, 2018. Covered in The Telegraph and The Tyee.

The key to harvesting data on large numbers of Facebook is gathering information about people who download an app, but also on their Facebook friends.

And despite Facebook’s claims to have blocked that kind of information gathering, The Tyee identified three vulnerabilities that still allow information on Facebook friends to be gathered without their consent or knowledge.

Facebook has fixed one vulnerability, saying it was already taking action when The Tyee reported the privacy weakness.

The corporation acknowledged that The Tyee investigation has led it to take action to fix another vulnerability that made it easier to connect friends handed over to Facebook apps to their public profiles, potentially opening them for data harvesting.

The Tyee agreed to allow Facebook to fix the vulnerability before reporting it.

A Facebook employee said it doesn’t plan to fix the third vulnerability, believing its safeguards are adequate.

But The Tyee investigation raises questions about the adequacy of Facebook’s privacy fixes after facing heat for its alleged role in the U.S. election outcome.

At the top of that list: how much information should be handed over about a Facebook user without their consent when a friend, perhaps unaware of the full implication, says it’s OK?

The Cambridge Analytica scandal

It helps to understand how the data was gathered for Cambridge Analytica to support Donald Trump’s successful presidential campaign before the original giant loophole was closed.

Imagine you wanted Facebook information on the 30 million Canadians over 15 for a political or marketing campaign.

So you created an app that would be attractive to users — a clever personality quiz or a game — or even paid them to sign up.

To download the app, they would be asked to give permission to download their Facebook information and the information of their friends. You could then harvest all that information — their likes, posts, activities — and store it in a database, constantly updating it.

The average Facebook user had 350 friends in 2014.

So, theoretically, to get information on every Canadian over 15, you would only need to persuade 86,000 people to download the app. (In reality, there would be some duplication and overlap, but you’d still have information on millions of Canadians.)

It was astonishingly easy to gather personal information on people without their informed consent. When Facebook users went to download the app, they simply had to click on a box like this in return for the chance to find out about their personality type or ideal partner.

Even when Facebook tightened the rules in 2014, it gave developers a year to keep gathering information on friends of people who had downloaded an app — a perfect impetus to grab and store as much information as possible.

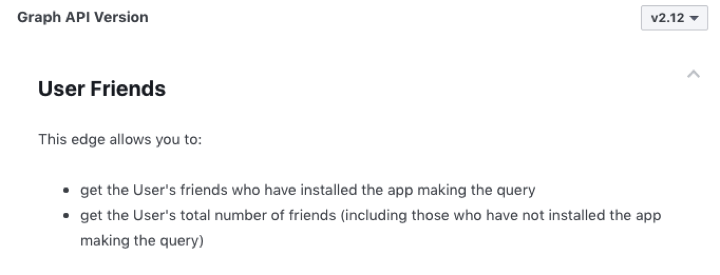

The policy change was supposed to end developers’ access to information on Facebook friends of users without their consent. Any company that wishes to make an app — web software that extends the functionality of Facebook and makes use of its network — has to use code from Facebook’s app cookbook called an API Reference. (API stands for application program interface.) Now the Facebook guide says:

So, in theory, you could get information about the number of friends of a person who downloaded the app, but not their friends’ personal information, unless they had also decided to do your survey or play your game.

But The Tyee found — and Facebook acknowledged to a degree — that it’s still possible to collect massive databases of largely publicly available data from profiles.

In 2015, Facebook limited developers’ ability to access information on all “friends” of people who downloaded an app unless they had also downloaded it.

But it’s still possible for developers to obtain information on a large group of app users friends, through the very same permission process.

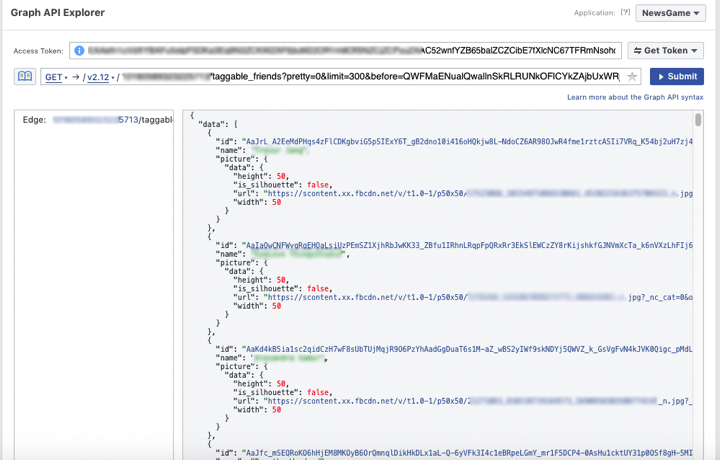

The first two security issues discovered by The Tyee concern the ability of developers to exploit a weakness based on their ability to access a list of “taggable friends.” These friends’ names are provided to the developer without being notified.

Taggable friends are typically the vast majority of a user’s friends — who isn’t willing to be tagged in a photo? Of my 420 Facebook friends, 381 are taggable.

App creators wishing to get this friend list must agree that they will only use the function to tag friends and must face a review from Facebook before they can launch an app that uses it.

However, once approved, app makers are not prevented from downloading data into external databases. After the data is on another server, Facebook can’t know what is done with it.

Even knowing people are an app user’s friends — based on what’s known about the app user — is revealing. Facebook is inconsistent in acknowledging the privacy implications in providing that information in its friend lists.

Once developers have the list of names, they are a step closer to extracting more data — any information on the people’s pages not set to private, including posts, likes, biographical information and more.

Facebook did limit the information developers get about these friends, and did not provide their unique Facebook IDs, which would allow more information to be fetched.

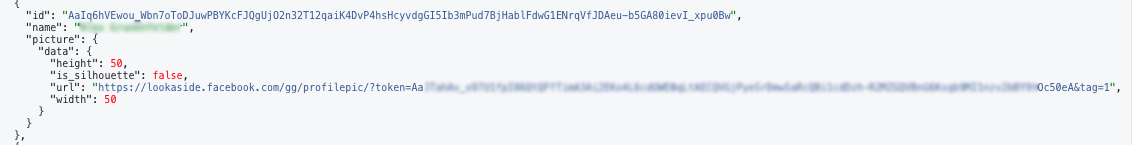

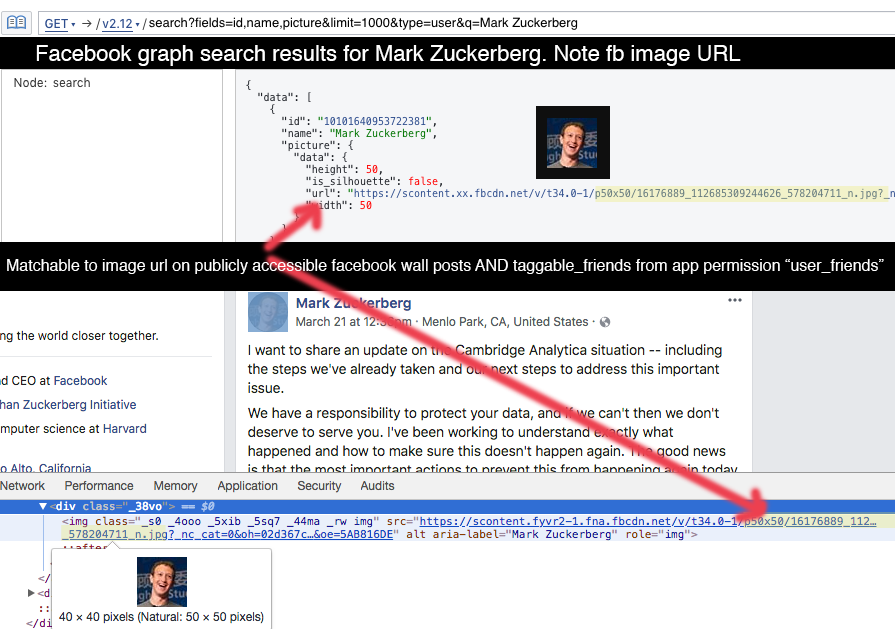

But the available information included full names and the web address of their profile photos. The address was long and, as The Tyee discovered, shared key identifying numbers and images used in the searchable Facebook user listing, making it possible to gather additional information.

With that information, even unsophisticated programmers could search for all the taggable friends, identify the address of the web photo and figure out the unique identifier of the Facebook user. With a little effort, they can confirm the ID and save all the public information on the person’s profile. It’s also possible to create a bot to do the searches and gather the information.

The Tyee reported the vulnerability to Facebook Saturday.

By the next day, Facebook had changed the way it provided the information on taggable friends. The photos are hosted on a new web domain, and the corporation removed the unique identifier from the image address and changed the format.

When the Tyee followed up, Facebook admitted that it had addressed some of the concerns.

“You're correct that we made some changes over the weekend to how we return profile photos on our platform (independent of your submission though). These changes have been in the works and are in the process of being rolled out right now.”

But the change didn’t fix the vulnerability. A programmer can still easily use the profile photos to search Facebook and harvest all the public information on people’s pages.

Facebook acknowledges the continued vulnerability, suggested that the complication and difficulty in gathering the information are adequate safeguards. Users have the option to set privacy settings to protect the information, the company noted.

Facebook pointed out that it has made efforts to educate its users about privacy settings and has set the default audience of new users’ posts to friends only.

But it will not change the way apps can obtain a secondary friend list, despite the 2014 recognition of the privacy questions raised by sharing names without users’ consent.

Facebook could easily make its policy consistent, providing developers with the names of only those friends who also installed the app while protecting the privacy of users who allowed tagging.

It remains simple to create a bot to search for a name given by the taggable list, confirm it’s the same person using the photo and save all the public information on their profile.

The third weakness concerns a publicly searchable Facebook user listing for developers that accidentally revealed a key unique ID about them used elsewhere, too.

Facebook fixed this issue, admitting it had no plans to before The Tyee brought it to their attention. This ID makes it easier to match these friends’ public profiles to the aforementioned “taggable friend” list.

What should you do?

If you’re skeptical about the information available, create a new Facebook account, visit your own page and consider how much a person or web-scraping bot could learn about you based on your information, posts, likes and photos. Or log out of Facebook and visit your profile to see how much even a non-Facebook user can learn about you.

The practice of systematically scraping publicly available web pages to build databases is in a legal grey area. Website owners want data to be available so that search engines will create traffic, but are reluctant to allow massive collection of data that’s valuable to them.

Owners — like Facebook — try to manage this with posted “terms of service” agreements limiting data-scraping.

Courts in the U.S have inconsistently enforced such agreements, but Facebook has been known to sue and cause anyone caught scraping to settle.

In B.C., a court awarded damages to real estate Company Century 21 after Zoocasa, a real estate site then owned by Rogers Communications, scraped content from real estate listings and posting them online in violation of the terms of service set by Century 21.

Zoocasa argued that it did not agree to the terms and that the reposting constituted fair use, however the judge rejected both arguments. The suit only cost Rogers about $31,000 — a pittance compared to the value of a large database.

Facebook and other sites also have algorithms designed to detect bot-like activity in order to block massive collection. They can force the visitor to fill out a “captcha” style form — typing in letters and numbers or identifying images — to ensure the visitor is a human, among other tactics.

But the information is valuable. That’s why Facebook is worth $465 billion. Collectors can learn to keep below the threshold that triggers such verification or even pay an overseas data farming operation to have humans browse and save data or defeat captchas.

It’s a game of cat and mouse — vulnerabilities will be closed and new ones exploited as long as there is valuable information to be had.

The important principle at play in all of this — easily understated but certainly well understood by Facebook and those that want its data — is that the more connections an app maker knows about between Facebook users, the more powerful the predictions and inferences it can make about any one “friend” in the database. Even if it may have little direct information about that friend.

Apps start with knowledge of one person. With access to information on taggable friends, developers know — at a minimum — about people connected to that person, people who did not consent to have that information shared..

Thousand of apps gather more data, more connections. Add to that all the public info that may be collected about those names, made easier by vulnerabilities only partly now addressed by Facebook.

In the end you have a very powerful database.

The argument that the data was already there on people’s Facebook pages doesn’t hold water. The information has meaning when you can identify relationships and have a starting point for gathering data.

It is no surprise that a firm like Cambridge Analytica collected valuable data from Facebook. Facebook exists to harvest this information and use it to target ads.

And it is in Facebook’s interest to delay implementing data privacy until outrage outweighs the benefits of exposing the data.

If you are thinking about quitting Facebook now, unfortunately the cat is probably out of the bag. And privacy is only going to improve thanks to the outrage over the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Will Facebook fix the vulnerabilities and become more serious about privacy? Will it limit the taggable friends list available to developers, as it did the regular friend list, to those who have installed the app?

It depends on your outrage.

If you do stay on with the book of faces, reading up about privacy controls and maximizing your settings can reduce your risks as new mass-scraping and information-gathering tactics exploit Facebook’s vulnerabilities. Check out EFF’s excellent guides

On an optimistic note, this new kind of Cambridge Analytica data, used to map out the segmented hopes and fears of a population, could have just as easily been used to develop democratizing policies.

That, among other reasons, is why I’m not leaving Facebook — for now. ![]()

Read more: Analysis

@bpcarney

@bpcarney

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: