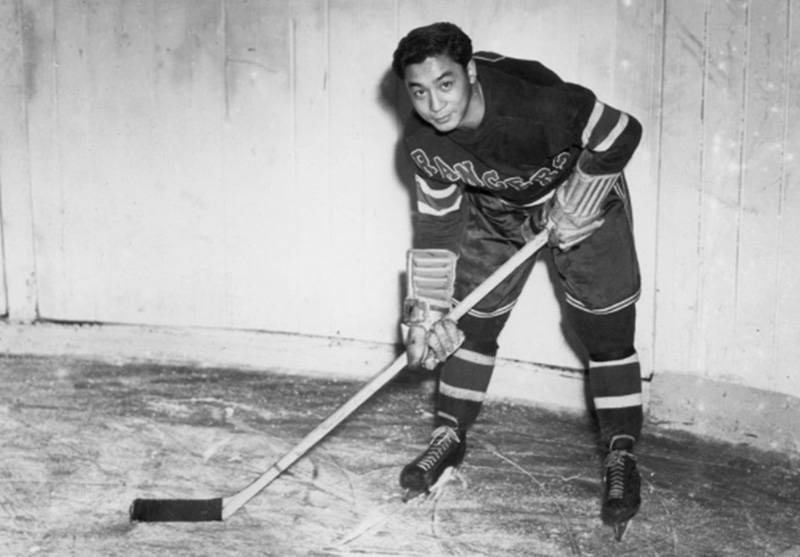

The Vancouver Canucks honoured Larry Kwong before Saturday night’s game, a nod to Chinese New Year. His daughter dropped the puck for a ceremonial face-off following a video tribute highlighting Kwong’s life and career — born in Vernon, played senior hockey in British Columbia, joined the army during the war, got scouted by the New York Rangers, played a single game in the NHL.

Kwong, 94, lives in Calgary where earlier this month he played host to a Chinese New Year dinner in his name. He is no longer mobile enough to make the trek to Vancouver, having lost both legs to poor circulation caused by diabetes, a particularly cruel fate for someone once so fleet on ice.

The video tribute touched on the adversities Kwong faced without going into detail. A pregame ceremony is not the time. In every part of his life, from his birth to his name to his citizenship status to the roadblocks he faced in pursuing a working life as a professional hockey player, Kwong faced off against discrimination. From the moment of his birth to a Canadian-born mother on Canadian soil, Kwong was considered a resident alien, a foreigner in his own land.

His father, Eng Shu Kwong, immigrated to Canada from a village near Canton, China. An immigration officer took his given name as a family name and he was known as Kwong ever after. He later panned for gold at Cherry Creek in the Okanagan before trying his hand at farming. Family lore has him walking over the Monashee Mountains to Vernon, where he bought a hardware store, which he turned into a grocery.

The two-storey building had a wrap-around balcony on the second floor, where the family lived. A Western false-front facade carried the store name in block letters — KWONG HING LUNG & CO. DRY GOODS & GROCERIES. The name meant "abundant prosperity,” spelled out on a wooden board at the entrance in Chinese characters.

He prospered as a grocer, marrying a Chinese-Canadian woman born in Victoria. He later took a second wife, paying her head tax to bring her to Canada. Into this unconventional extended family a boy was born on June 17, 1923. He was named Eng Kai Geong as well as Lawrence Kwong, the name that appears on the identity card issued to his parents by the federal immigration department. He was the 14th of what would be 15 children. His father died when he was five.

At school, young Larry daydreamed about hockey. On Saturday evenings during the Depression, the family gathered around the radio to listen to Foster Hewitt describe the derring-do of hockey players from Maple Leaf Gardens in far-off Toronto.

The boy begged his mother for a pair of hockey skates of his own. She finally relented, buying a pair too large for his feet, figuring they would last longer as he grew into them. The boy stuffed the toes and wore extra socks.

“In those days, we didn’t have enough money for hockey gloves or shin pads,” he once told me. Catalogues were shoved into socks as protection against wayward pucks and slashing sticks. The Kwong boys trudged six miles to a favoured frozen slough in the backwoods called Mud Pond, where they played shinny for as long as the sun was in the sky. He never played an organized game of hockey — or even one indoors — until he joined the Vernon Hydrophones at 16.

The diminutive forward was a scoring sensation for Vernon, potting goals by the bushel thanks to his speed and a stick-handling prowess perfected from hours on frozen ponds. The Hydrophones won a provincial championship, earning Kwong a try-out with the Trail Smoke Eaters, a semi-professional team which had claimed the world championship in Zurich just two seasons earlier.

The young man was eager to leave Vernon, where opportunities for a young Chinese Canadian were limited. A spot on the Smoke Eaters’ roster was coveted throughout the province because with it came a high-paying job at the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company. Kwong made the team, but didn’t get the job because of the company’s discriminatory hiring practices.

The team instead arranged a position for Kwong at the Crown Point Hotel — as a bellhop. He took a room upstairs. Every time he stepped out of the hotel lobby onto Bay Avenue he could look north to see the belching smokestack of a smelter where he could not work.

With war raging overseas, Kwong moved to Nanaimo to build minesweepers by day in the docks and skate for the Nanaimo Clippers at night. At just 5-foot-6 and 150 pounds, he was a tempting but elusive target for opposition tough guys.

He spent most of the 1943-44 season playing senior hockey with the Vancouver St. Regis while staying in the sponsoring hotel.

Kwong was invariably described as a “Chinese iceman” or “Chinese puckster” in the sports pages, where he was dubbed the China Clipper and King Kwong, a teasing pun for so tiny a player. Even though he was just 20, he expressed a weariness at being the lone person of his ethnic background playing the sport in a hockey-mad land.

“The fans like to see a Chinese player as a curiosity,” he told Alf Cottrell of the Vancouver Sun. “That’s my good luck. But it has disadvantages. Ever since I was a midget there has always been a player or two trying to cut off my head just because I am Chinese. And the bigger the league the bigger the axe they use.”

In the spring of 1944, he enlisted in the army. For basic training, he was dispatched to Red Deer, Alta., an assignment made because the local army hockey team needed a sniper. He arrived in time to play a couple of games for the Red Deer Army Wheelers. The bloodlust enemy was neither Nazi Germany nor Imperial Japan, but rather a navy team in Calgary and an air force team in Edmonton in the Central Alberta Garrison Hockey League.

Years later, when asked what he did during the war, Kwong would joke in his dry manner that he had fought in the Battle of Wetaskiwin.

The army team exposed him to top-calibre players, as each branch of the military stocked their squads with such NHL stars as Max Bentley, the ace of the Calgary team. To Kwong’s satisfaction, he held his own.

After the war, he returned to the Smoke Eaters for a season. His reputation earned him an invitation and a train ticket to a tryout camp in Winnipeg in September 1946. The New York Rangers called on 57 unsigned players to scrimmage at the Amphitheatre under the watchful eye of Rangers coach and general manager Frank Boucher. Seventeen were signed to minor-league contracts, Kwong among them. He was assigned to the New York Rovers, a farm team which shared Madison Square Garden with the parent club.

On Nov. 17, 1946, Kwong was greeted at centre ice at the Garden by a delegation from Manhattan’s Chinatown officially welcoming him to the city.

He emerged as the club’s top scorer in his sophomore campaign, averaging better than a point per game. Through two seasons, he saw other, perhaps lesser, players called up to the Rangers and wondered when his chance would come.

Finally, in March, 1948, he got the call after several Rangers forwards were injured. Kwong, a right winger, and teammate Ron Rowe, a centreman, were to join the Rangers for the train trip north to Montreal for a Saturday night game against the Canadiens at the Forum.

He sat in the visitors’ dressing room at the fabled arena, nervous at the prospect of making his debut, of opposing on ice the players whose feats he had heard described on the radio. As his new teammates tiptoed out on skates, each in turn tapped a stick on the rookie’s shin pad for luck. “Do your best,” Buddy O’Connor told him.

Kwong and Rowe sat at one end of the Rangers bench, waiting for the call from coach Boucher. The first period passed in a blur with the rookie firmly planted on the bench.

He waited for a call in the second period. It never came. By then, the Canadiens led 1-0.

“Waiting and waiting and waiting,” he once told me. “Just sitting there waiting. At the end of the bench.”

The third period was a frenzy. Elmer Lach scored to make it 2-0 for the Canadiens. Less than a minute later, Edgar Laprade got a puck past Montreal’s Bill Durnan to make it 2-1. Defenceman Frank Eddolls tied the game on an assist from O’Connor before Ken Reardon converted a pass from Rocket Richard to restore the Canadiens’ lead to the delight of the 11,000 partisans in attendance.

And still Kwong waited.

Finally, at last, he got his orders. Out onto the ice.

It was a whirlwind during which he didn’t get a shot, commit a foul or, blessedly, be responsible for a goal against. Then it was time for a shift change.

Just like that, he was back on the bench.

“The Rangers used Larry Kwong, first Chinese player in the league, only sparingly,” the New York Times reported after the game.

He did not yet know it, but the beginning of his NHL career was also its end. No goals, no assists, no shots, no penalties, nothing but a name on the official scoresheet.

It lasted less than one minute. A New York minute, some would later describe it, a hectic, impatient accounting of time lasting somewhat less than 60 seconds.

The very next day, Kwong returned to New York and suited up for the Rovers. (Rowe got to hang around the Rangers for four more games, scoring a single goal.)

“How can you prove yourself in a minute on the ice?” Kwong once asked me before answering his own question. “Couldn’t even get warmed up.”

The season with the Rovers would be his last in the Rangers organization. If they didn’t want him, he’d find some team that did.

The Valleyfield Braves, based in a Quebec industrial and port city on the St. Lawrence River southwest of Montreal, offered Kwong a salary, a $5 bonus per point and a job rolling barrels of alcohol off the train at the Schenley’s whisky distillery. In time, he opened his own namesake restaurant across from city hall, employing 32 workers.

The playing coach in Valleyfield was Toe Blake, a former NHL star who would go on to lead the Canadiens to eight Stanley Cups in 13 seasons behind the bench. Kwong was a star playmaker for the Braves, leading the league in assists in 1950-51 as he guided the club to the Alexander Cup championship. He won the Byng Trophy as the league’s most valuable player.

The following season the top goal scorer was a rookie named Jean Beliveau, who scored 45 goals for the Quebec Aces. Kwong had 38.

He spent seven comfortable years in Valleyfield before embarking on a wanderlust tour of hockey’s lesser-known hotspots. Parts of two seasons were spent in Ohio with the minor-league Troy Bruins. Another season was spent with the Nottingham Panthers in England. He then played and coached in Switzerland for a decade.

By the time he returned to Canada to work in the family grocery enterprise, based in Calgary after the Vernon business was sold in 1945, Kwong was a forgotten athlete. Even his China Clipper nickname had been usurped by sports writers describing football’s Normie Kwong, no relation, who would go on to serve as Alberta’s lieutenant general.

After the civil rights movement changed popular attitudes about race, Willie O’Ree, an African-Canadian player from New Brunswick, would be celebrated for having broken the NHL’s colour barrier, though he did not break into the NHL until 1958, a decade after Kwong’s game.

Kwong never spoke up, in part because no one asked him about his experience. He was overlooked except for the rare newspaper profile. A decade ago, his story caught the attention of Chad Soon, a school teacher in the Okanagan, who had first heard of the player from his grandfather. He befriended Kwong before launching a campaign on his behalf to gain rightful recognition.

Kwong was feted for being the first player of Asian ancestry in the NHL, for being the first player of colour, for being the first player from the Okanagan region of British Columbia. He was featured on the CBC’s The National in an 11-minute report and he was mentioned in the New York Times for the first time since his lone game. A documentary was filmed about him and a short book written. He gained induction into the BC Hockey Hall of Fame and the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

Soon was unable to attend the Saturday night ceremony at the Rogers Arena, as he was coaching his son in a basketball playoff game at the Civic Arena in Vernon, where Kwong played his first indoor hockey game with the Hydrophones seven decades ago. Soon said he was thankful to his hockey hero for “changing the game and changing minds.”

In Kwong’s story, the activist Todd Wong, a library assistant in Vancouver, sees an echo of the story of the Chinese Canadians in the province who persisted in the face of discrimination.

“We have felt ‘as Canadian’ as other people,” Wong said. “We grew up playing hockey. My uncles and grand uncles fought for Canada in the Second World War. And yet, like Larry, they were called names, not given jobs, even beaten up for looking different.”

Wong attended the Canucks game, sitting alongside 93-year-old Georgina Kwong, Larry’s sister-in-law. Every time the Canucks scored, she said, “Kwong clan brought the Canucks luck.” The Canucks upset the Bruins by 6-1.

In Calgary, Larry Kwong remains sharp of mind despite his advanced years, though his memory has faded. He no longer can recall specifics of his single game in the NHL.

Oddly enough, people know more about it now than ever before. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: