In recent weeks, pollsters have asked us questions about UFOs, cyberscams, the coming federal election and Metro Vancouver's transit plebiscite. But there's one question many of us are asking the pollsters: Why should we believe you?

The 2013 B.C. election fail did for the polling industry what the Hindenburg did for the dirigible as the last word in air safety. Since then, pollsters have been struggling to find ways to better measure what we're thinking.

For pollsters, there's no money in asking questions about elections and releasing the numbers to the media. They do it as a marketing tool to attract clients who want to know what people think about, say, shampoo.

Because the numbers in marketing surveys are difficult to verify, calling elections correctly is one of the few ways pollsters can show they know their stuff. Calling elections correctly, however, is becoming increasingly difficult. And bum results don't attract clients.

University of British Columbia political science professor Richard Johnston said he understands their plight. "If I were in the firms I would almost ask myself, 'Is it worth it to be in the prediction business?'" he said.

But if pollsters quit doing public polls, voters are left with less information, said Johnston. Voters have a valid interest in knowing how their fellow citizens are going to vote because it allows them to decide how to vote most effectively, he said. "If you can't make sense of the polling information, then what do you do?"

Making sense of polls on the Metro Vancouver transit plebiscite may be particularly difficult because of the nature of the vote. Pollsters face enough challenges tracking opinion in traditional elections, which end with most voters marking their X on a single day at the end of the campaign.

But the transit ballots will be trickling in by mail until the end of May, even as the campaign intensifies. Insights West, whose polls found a steady erosion of support for the Yes side, has stopped polling on the question, even though there are almost two months left in the campaign.

The decision to stop is based on a legal interpretation of the section of the Elections Act that prohibits the release of poll results on election day. Legally, it could be argued that election day for the transit plebiscite began in mid-March, when people got their ballots.

Obviously, a lot can change before the end of May.

The next few months will also see a swarm of federal election polls, and pollsters will be hoping for a result that restores their reputations. This election, however, may fit a pattern that UBC's Johnston says goes back more than a decade.

Provincial and federal election polls have tended to under-represent support for the incumbent party. It's not clear why; one theory blames it on the "shy Tory" -- right-wing voters who don't want to admit their allegiance to pollsters.

Johnston notes, though, that the pattern doesn't include just right-wing incumbents. Pollsters tended to under-predict the performance of the federal Liberals in 2004 and 2006, he said.

It's possible that risk-averse voters decide at the last minute to vote for the governing party, he said.

Johnston has this advice for someone trying to make sense of federal election polls: "If the pattern persists, I guess I would probably add a couple of points to the Conservative totals. I'm not sure how much I'd hedge, but I'd hedge some."

New techniques in 'experimental phase'

As Johnston's comments suggest, people are still trying to figure out what's behind the polling industry's woes. The 2013 B.C. failure followed a blown call in Alberta the year before, when the incumbent Progressive Conservatives surprised everyone by beating the Wildrose party. There was evidence to suggest that Albertans changed their minds at the last minute -- after the last polls were taken -- and stampeded away from Wildrose.

Pollsters vowed to avoid that mistake in the B.C. election, and polled pretty much up to the last minute. After the B.C. results came in, some pollsters argued there had been a similar late switch in B.C., with voters intending to vote for the New Democrats right up to the moment they marked their ballots.

Other pollsters thought they had weighted their data incorrectly. No poll sample looks exactly like the population at large, so pollsters weight, or adjust, the numbers. A sample may have more men than women, say. Because we know women tend to vote differently from men, a pollster will give more weight to the opinions of the women in the sample.

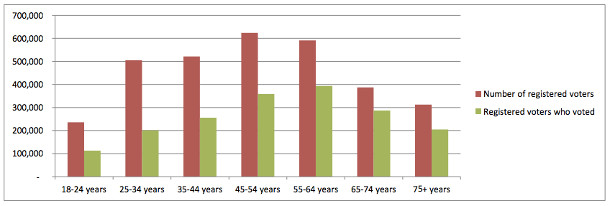

Usually, pollsters weight their samples based on census figures for things like gender and age. That makes the sample look like the general population, which is great if you want to know what British Columbians or Canadians as a whole think. But the group of people that turns out to vote doesn't look like the general population. The people who make the effort to go to the polls tend to be significantly older, for one thing. (See chart below.)

It also appears that the people who answer polls tend to be older, just like the people who vote. Which means that, by weighting towards census data, pollsters were moving their numbers away from the "true" result, rather than toward it.

UBC's Johnston said he understands why pollsters weight their data, but adds that "weighting can be a dangerous business."

He said that when he was the research director of the National Annenberg Election Survey at the University of Pennsylvania, he and his colleagues experimented with different weighting schemes.

"Frankly, everything that we did made the prediction worse," he said. "The best thing to do was just to take the data as it came in."

After the B.C. election, pollsters also talked about the need to develop likely voter models -- procedures that predict the probability of a survey respondent turning out to the polls. These normally go beyond weighting to include such things as past voting behaviour.

A number of firms have begun using such models. These firms offer two results for each survey: one for "eligible voters" that's based on traditional methodology and a second for "likely voters" that's adjusted according to their model.

It's a process that still has some bugs to work out. As poll watcher Éric Grenier of ThreeHundredEight.com wrote of the June 2014 Ontario election, "Every pollster that used a likely voter model did worse with it than they did with their estimates of eligible voter support."

Grenier concluded: "Clearly, the likely voter models are still in an experimental phase. When employed in Nova Scotia and Quebec, the first time we have seen them used in recent provincial elections, they only marginally improved the estimations, if they did not worsen them.

"We may come to the conclusion, then, that for the time being Canadian polling is not yet capable of estimating likely turnout with more consistent accuracy than their estimates of support among the entire population."

Angus Reid, the veteran Vancouver-based pollster and head of the Angus Reid Institute has adopted a likely voter model. In a "Note on Methodology" accompanying its polls, the firm states:

"We have developed this approach because we feel strongly that it is the responsible thing to do when reporting on electoral projections. With declining voter turnout, there exists an increasingly important divergence between general public opinion -- which still includes the still valid views of the almost 40 per cent of Canadian adults who don't vote -- and the political orientation of the 60 per cent of likely voters whose choices actually decide electoral outcomes."

A spokesperson for the Angus Reid Institute was not available to speak to The Tyee for this article.

Without analysis, 'pollsters will sit elections out'

Pollster Mario Canseco, a former vice-president at Reid's former company, Angus Reid Public Opinion, said offering two different results side-by-side is "absolutely ridiculous in my view." He compared it to a hockey analyst predicting that the Rangers will win the Stanley Cup, but if the Kings are more motivated, they will win.

Pollsters need to be more open with their data and methodology, said Canseco, now vice-president at Insights West.

In an article written late last year for the in-house magazine of the Marketing Research and Intelligence Association, Canseco argued that this is a crucial time for the polling industry.

"The recent misses in Canadian provincial elections have brought increased criticism to our craft," he wrote. "Unfortunately, this criticism has not led to greater scrutiny. The best way to deal with this quandary is to establish new guidelines for the publication of poll results and have a deeper conversation -- with the media and the public -- about what the numbers we publish actually represent.

"If we decide to carry on as if nothing happened, we run the risk of the media relying on internal polls that nobody has seen, with pseudo-insiders taking advantage of the low data literacy of reporters... If we don't take time to analyze what recent experiences mean to our industry, we will fail. Pollsters will sit elections out, and the only electoral information available to the media will be coming out of the campaigns themselves."

Canseco said in an interview that Canada needs standards similar to those of the British Polling Council, which requires members to make a wide range of data, including weighting schemes, available. That ensures a level playing field, he said.

In Canada, pollsters tend not to publish such information because they don't want their competitors looking at their numbers, Canseco said. Unless everyone has to do it, disclosing all your data is like "showing your playbook" to the other team, he said.

Pollsters get criticized a lot these days, especially on social media and especially by people who don't like the results, Canseco said. But, he added, it's important that pollsters continue to do public affairs polling and learn from their mistakes.

"You get up and you try to do it better the next time," he said. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Election 2015, Elections

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: