Call it a blessing, a gift or act of faith.

Or maybe call it sheer stubbornness.

In 2009, what was historically Winnipeg's largest church -- built in 1913, rebuilt in 1944 after a fire -- was beset by leaks on all four corners, black mould, asbestos, and basement floors you could put your foot through in places.

As Rev. Cathy Campbell, puts it, St. Matthew's Anglican was a "sick, dying building," with a shrinking congregation. Years of talk, often heavy with fear and loss, about renovating, moving, or closing had hit a wall of seemingly insurmountable costs. "The congregation was just not strong enough financially or in terms of human capacity to do things to renew it on its own," she recalls.

At the same time, "It was also really a vital centre in and for the neighbourhood," explains, listing the building's vibrant drop-in centre, low-income food programs that serve more than 800 people a year, its community garden, aboriginal and non-profit organizations.

Then there came the day when a gas worker stood at the door, "with a wrench in his hands," ready to cut off the gas. "Right at that tender time," Campbell says, St. Matthew's received two unexpected bequests, one from a stranger to the current congregation worth roughly $500,000.

"Suddenly the congregation had a real choice," Campbell says: take the half-million, plug the leaks, and survive until the money drained, or do something much more radical. With affordable family housing in severe shortage in the Manitoba capital's inner-city, the church "could take the gift that came to it and gift it on -- invest it in a housing project."

As long-observed societal shifts thin membership rolls and budgets, the Winnipeg church is hardly alone in its financial woes. But its recipe for doing good in its community, while also finding a path for its own survival is one that's catching on among Canadian faith communities across the religious spectrum.

To address housing crises simmering in most major cities, some faith groups are partnering with private developers. Others are becoming developers themselves. Still others have found creative ways to cut building and mortgage costs.

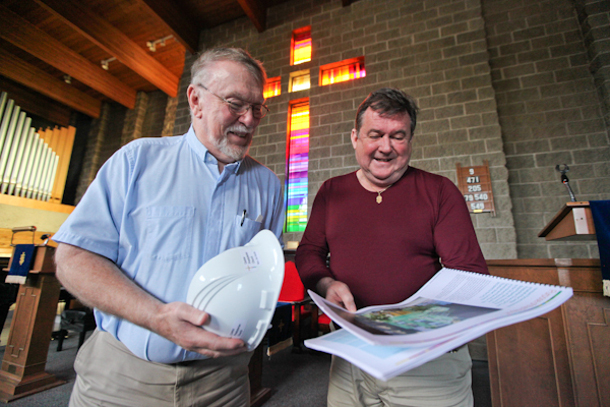

In St. Matthew's case, its West End Winnipeg property held little value. The church had no luck attracting a private developer. So it followed its own star, combining government funding in exchange for more below-market family units, and its own sheer effort to fundraise $1 million.

Late this September, after months gutting and rebuilding the building's interior, the congregation held its first worship service in its new, much smaller space -- on property it now shares with 26 new affordable housing units.

To do that, St. Matthew's and another congregation created a non-profit building society, to which it transferred ownership of its church building. It then renovated and reconfigured its former sanctuary, and became just one of many tenants under its own roof. It’s since begun welcoming families into the apartments, three-quarters of them rent-geared-to-income and the rest renting at below-market.

Rising soon in BC

In B.C.'s Lower Mainland, several churches are taking similar paths, though not always for the same reason.

In Vancouver's West End, for instance, Central Presbyterian Church is poised to begin a complete re-construction to replace its current building with a new one, featuring a dedicated worship sanctuary, commercial space, 168 market rental suites, and 45 units of non-market housing for neighbourhood seniors squeezed by rising costs.

Like St. Matthew's, Central Presbyterian is home to an array of community services and activities. Unlike the Winnipeg church however, it was outgrowing its old space.

Also unlike Campbell's Winnipeg congregation, which opted to partner with government and hire an outside developer, Central Presbyterian engaged Vancouver-based Bosa Properties as a "construction partner" with experience, while the church's new non-profit society took on the role of developer.

Construction will begin next year, as soon as pastor Rev. Jim Smith can find a temporary home for his congregation. For him, there is little sentimentality attached to the brick-and-mortar of tradition; instead, a sense of what his church is here for: to serve.

The greed-free developer

While St. Matthew's and Central Presbyterian have charted their own paths through the wilds of housing development, another B.C. organization proposes to package the process for other faith communities.

"There seems to be a movement," says Robert Brown, president of Catalyst Community Development Society. "People [in faith communities] are figuring out ways to use their assets and make a difference with them."

His non-profit organization's pitch combines business prudence and charitable motives: "Can we leverage their assets to provide them not only more flexibility -- usable multipurpose space they can share with other groups and share the operating cost -- but also have them retain an ownership position?"

Catalyst is something of a unicorn, a real estate developer without a profit motive. Brown, who launched Catalyst a little over a year ago after nearly four decades in private housing and commercial development, had been volunteering with struggling charities when he spotted a gap in their capabilities he thought he could fill.

"The churches we work with are typically suffering from what a lot of them are: declining congregations, in buildings reaching the end of their useful life," he explains. "They're looking at a redevelopment that can reposition themselves and create more financial sustainability."

Yet, he found, "even if they owned the land or the building, they couldn't develop it because they'd say, 'We're not developers, we can't be taking that risk.'" Some feared that tensions would arise between commercial ambition and their social and spiritual mission.

Catalyst's non-profit stature helps soothe those doubts. With Brown's real-world expertise, it acts as the developer, raising capital mostly from conventional lenders but splitting ownership of the completed projects with its church partners. (See sidebar for details).

"It functions just like any other developer does," he says. "We look for opportunities to develop real estate, and we bring cash equity to the table to help the development... We're trying to take [churches'] assets and create community benefit."

The approach can work across the spectrum of affordable housing in the Lower Mainland, Brown believes, from affordable rental to social housing, even to attainable homeownership.

"We're looking at one outside Vancouver," Brown says. "A church where [units in] the project may be sold at low market ownership rate," (he declined to name the congregation because talks are still exploratory).

Building on many faiths

It's not just Christian churches taking a leap of (housing) faith. Other religious communities are also moving beyond traditional charitable roles to help those needing affordable shelter.

Canadian Muslim organizations are finding creative ways of to address the challenge posed by Islam's prohibition on usury (lending with interest; in Arabic: riba).

In the Greater Toronto Area, community members are tackling this by forming co-operatives that help finance their Muslim members' housing through shared equity, without any interest payments. Members can get into a home if they buy enough shares in the co-op.

"Unfortunately, for the last three decades, Muslims in North America have been facing a moral dilemma," states the Ansar & Islamic Co-operative Housing Corporation Ltd. on its website. "Whether [to] purchase a house and indulge into interest or, forget buying a house altogether to avoid the interest."

Although motivated by doctrine, the shared-equity co-operative approach might offer lessons in affordability, by cutting for-profit financial institutions out of the loop while making first-time homeowners eligible for tax credit.

A similar non-profit, the Scarborough-based An-Nur Co-operative Corp., draws on the traditional Arabic concepts of musharaka (creating a joint venture partnership) and murabaha (paying the cost-plus-basis on a home) to offer co-op members homes at lower than for-profit-housing costs, with a 25 per cent down payment and monthly instalment payments. The organization dubs it, "A Canadian solution for Canadian Muslims."

In the same city, middle-income Jewish families, struggling to afford to live near their community's services and facing rising poverty rates, are benefitting from a 32-year-old creation of Toronto's United Jewish Appeal Federation. Created to manage its philanthropic housing efforts, Kehilla today partners with developers, builders and landlords to offer rental subsidies to tenants.

Employing a creative financial side-step pioneered by Toronto's Options for Homes, Kehilla also issues second mortgages to would-be homeowners that helps put them over the threshold of a down payment.

"We don't serve the most religious parts of our community, they tend to do their own thing," says Kehilla's executive director (and former Toronto city planner) Nancy Singer. "Our doors are open to everyone."

In partnership with supportive developers and builders, the organization has helped a synagogue, a community centre and a school to redevelop their existing properties into housing.

'A reason for being here'

Back in Winnipeg, St. Matthew's congregation celebrated its historic red-brick building's re-launch as a home for prayer, community services, and now much-needed affordable housing, on the feast day of its namesake saint.

Despite a longer-than-expected ordeal of reconstruction, Rev. Campbell says she's glad her congregation chose not to simply sell its building and move somewhere smaller.

"We were cutting against a pure economic rationality," she reflects. "We were doing this for a mission: because it was needed."

That mission, she says, arose from the church's "faith commitment" to its neighbourhood and its neighbours: "The people here matter, and we have a reason for being here."

Her advice to other faith communities facing similar challenges? "Keep mission-oriented, and not just survival oriented," she suggests. "If we start becoming discouraged and cynical, so little will grow in that soil."

"At their core, the faith traditions have lots of say about the power of free gift-giving," she reflects. "What comes to us is gift; we're thankful for it, and we pass it on.

"This whole project is really a testimony to the creative power of gift-giving, which has a different dynamic than buying and selling."

Please note our comment threads will be closed Dec. 22 to Jan. 5 to give our moderators a well-deserved break. Happy holidays, readers. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture