While rising real estate values have made British Columbian homeowners among the richest people in the world, they are also a major driver of inequality, particularly between the generations.

Expensive housing, high youth unemployment and falling wages for entry-level jobs, mean young people see a future with much less opportunity than their parents had.

"We all know housing prices are higher now than they were a generation ago," said Paul Kershaw, a University of B.C. professor focused on social care, citizenship and the determinants of health. He is also the 39-year-old founder of the Generation Squeeze advocacy group and enthusiastically shares statistics to support his argument as if giving a Ted Talk.

Since 1976 the price of residential real estate has gone up by 240 per cent in Metro Vancouver, said Kershaw, citing Canadian Real Estate Association data. After adjusting for inflation, average housing prices are up by $165,000 in Canada and by $350,000 in B.C., he said.

For owners like his mother, that's great, he said, but it's "crushing the dreams" of their kids and grand kids.

Young people today are more likely to go to college or university than previous generations, but over the same period tuition fees have doubled, he said. They're twice as likely to have degrees, a distinction that comes along with high levels of student debt.

At the same time job prospects have diminished, with many young people working as unpaid interns or in low-pay positions to get established, he said. Compared to 1976, using inflation adjusted Statistics Canada figures, the typical wage for 25 to 34 year olds has dropped by $3 an hour across the country.

The drop in B.C. has been even larger, with a decline of $4 an hour, he said.

Here's how the Generation Squeeze website summarizes what's happening: "Generations raising young kids are squeezed for time at home. They are squeezed for income because housing prices are nearly double, even though young people often live in condos, or trade yards for time-consuming commutes. And they are squeezed for services like child care, which are essential for parents to deal with rising costs, but are in short supply, and cost more than university."

Income drop

Kershaw has plenty of company raising alarm about the reduced prospects for young people.

A recent personal finance column by Rob Carrick in The Globe and Mail reported on research by Markus Moos, an assistant professor at the University of Waterloo.

In 1981, the average income for people between the ages of 25 and 34 was $38,335 in Metro Vancouver, he wrote. By 2006, after adjusting for inflation, that had fallen to $31,844, a drop of 16 per cent.

As a 25-year-old contact with Asperger's syndrome who is receiving disability payments put it, "There's a lack of work for young people... A lot of jobs now are based on the ability of people to put a big smile on their face and be a good service worker."

The president and CEO of the B.C. Business Council, Greg D'Avignon, pointed out that Canada has brought poverty among the elderly to a level that's among the lowest in the world.

Various policies, including things like how health care is funded and the way we deal with property taxes help out seniors, who as a group are relatively good at making their voices heard on issues that affect them, he said. "We're clearly putting disproportionate resources into that age group."

Meanwhile many young people are in need, he said. The unemployment rate for youth is around 14.5 per cent, more than double the rate for people between the ages of 25 and 54, he said. "Again, that's where some of that frustration comes in."

Classes divided

Some, however, see focusing on the generational divide as a distraction.

"I think it's about class, not generations," said Bill Hopwood, an organizer of the Raise the Rates Coalition, when I asked him about Kershaw's message about generational inequality. "It's not that we're stealing from the future, it's that the rich are stealing from all of us."

And Sharon Keen, who at retirement age is financially stretched just to pay her rent, said she objects to Kershaw's thesis. "I don't agree. Two out of three boomers don't have pensions. Especially the women, like me."

Kershaw agrees inequality exists along various lines. "I think we often have inequality when we have different power dynamics," he said.

Those points of inequality may include gender, class, income or race, for example, he said. In Canada, and in B.C. in particular, they include a colonial legacy where people of First Nations descent are worse off than the general population on most any indicator of health, education or well-being.

"They're all characteristics of our identities that intersect," he said.

Seniors, for the most part, however, are doing much better than they were a generation ago when one out of three had a low income, said Kershaw. Governments of the day responded to the crisis, he said, and the public now spends $45,000 a year per person over the age of 65 through programs including health care, old age security and the Canadian Pension Plan.

That compares to $12,000 per year per person under 45 years old, he said.

And while many young people suffer to make ends meet, Canada has one of the lowest rates of poverty for seniors in the world at five per cent, he said.

Help needed

The country has a history of responding to social challenges such as seniors' poverty, said Kershaw. "Right now we're not doing that for younger generations," he said. "The problem is we seem unwilling to modify that adaptation for Gen-X and Gen-Y."

In some ways, these questions are non-partisan, said Kershaw. During the recent provincial election both main parties would have increased spending on health care, which mostly goes to older people. At the same time neither was prepared to spend $1.5 billion to make childcare affordable.

"It reflects the reality of power politics," he said. "Platforms are going to get organized around who shows up."

There are well-organized and vocal groups like the Canadian Association of Retired Persons that represent the interests of seniors, a demographic that votes in large numbers, but not young adults, said Kershaw. "It's not on the radar of any political party."

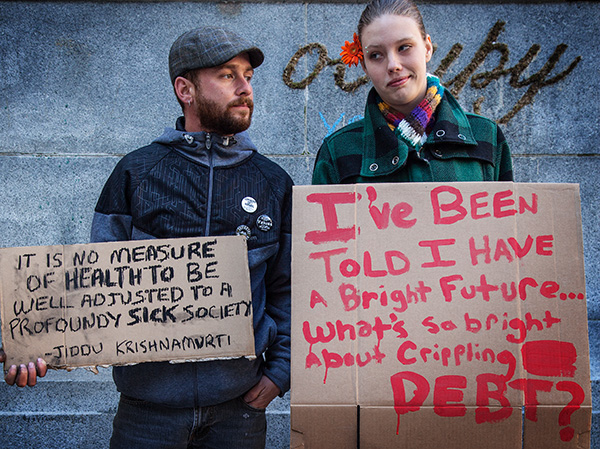

Even the Occupy Movement ultimately did little to highlight the challenge young people face, he said. "I think the Occupy Movement totally distracts from generational issues," he said, adding the slogan "We are the 99 per cent" masks large variation.

People who are over 55 years old today are the richest that age group has ever been, he said. "Canada's middle class isn't being squeezed per se. Canada's younger generations are being squeezed."

Ways to mitigate

There needs to be a public push for a better deal for younger generations, said Kershaw. "We could mitigate it by trying to keep tens of thousands in their pockets in their early adult years."

Housing prices and wages are determined by markets, making them difficult to change, he said, "Unless you're talking about breaking up capitalism, and I don't think many of us are."

Government policies that help people when they're starting to have children would make a big difference, he said. It would be possible to lengthen parental leave to 18 months and to raise the dollar amount of benefits, he said.

The public could also fund childcare to bring fees down to $10 a day, he said. That would still be higher than the rates in Quebec but much better than they are now in B.C. where daycare can cost more than university tuition.

Such policies could help young people at a key time in their lives by saving them as much as $50,000, which they could use to pay off student debt, accumulate a down payment on a home or save for retirement, Kershaw said.

It's not enough for the government to say it's creating jobs for people, he said. Jobs are important, but middle income jobs pay less than they did a generation ago, while housing prices have gone up and pensions have become less common.

He blamed the failure to act at least in part on neoliberalism and the hollowing out of government. Programs like health care that now exist are allowed to grow, but anything new is seen as too expensive.

That in turn has young people feeling disconnected from their governments and realigning their expectations.

This article is part of a series for The Tyee Solutions Society looking at the causes, costs and potential solutions for wealth inequality in British Columbia, Canada's most unequal province by some measures.

Monday the series continues: "New Economy, New Expectations": Some respond to reduced opportunities by building the economy they want. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: