[Editor's note: The 20-year effort to create modern treaties between B.C. First Nations and the federal and provincial governments has not produced many agreements. Underlying the challenge are complex structural relationships between First Nations that more than a century of colonial influence has aggravated. This four-part series by Carly Wignes looks at the deep tension one potential treaty has created, how others have succeeded, and the complex history that makes it so difficult to redress longstanding inequity.]

The letter from the chief of Sechelt Indian Band warned members of the Tla'amin that the friendly relationship between the two Coast Salish First Nations neighbours would not extend onto the soccer field. When it was read aloud, laughter filled the room. Representatives from each community had come together in Sliammon, just north of Powell River on the Sunshine Coast, in August 2011 to sign a shared territory agreement. It became just one of six so-called Shared Territory Protocols that Tla'amin First Nation signed with its neighbours, including the Klahoose, Homalco, K'omoks, Nanoose and Hamatla people, to outline where the signatories may hunt, fish and gather resources and to clarify the primary responsibilities that each would have regarding the economic development of treaty settlement lands.

When a majority of Tla'amin members, located just outside of Powell River, voted in favour of the Tla'amin Final Agreement in July, the First Nation came one step closer to implementation of its treaty, which now awaits provincial and federal approval. Chief Negotiator Roy Francis, who has been negotiating on behalf of the Tla'amin community since the process began, said the trick to getting along with your neighbours is to build upon the "principle of permission."

"It just goes back to older traditional times when we would be going into territories that were not ours. It was just a value that you would go and visit the occupiers of the area," he said. "We've been able to now complete arrangements with all of our neighbours on that principle."

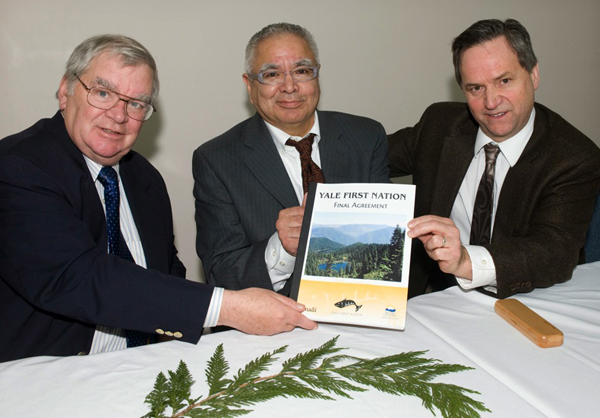

Such amicable relations have not been achieved by all First Nations in B.C. Differences between the Yale and Stó:lō First Nations, who share claims to a stretch of land along the lower Fraser River, demonstrate how immensely challenging it can be to resolve shared territory disputes. The Stó:lō people, who maintain the Yale are part of the Stó:lō community, say the imminent Yale First Nation treaty includes a stretch of the Fraser River that belongs to all of the Stó:lō. Despite the absence of any agreement or dispute resolution protocol regarding the land, the Yale Final Agreement received provincial approval in June 2011. Now, the agreement must only be approved by the federal Parliament to become the third finalized modern treaty in the province.

When the modern treaty process was first established, the B.C. Claims Task Force, established by the federal and provincial governments and the First Nations Summit to investigate how treaty negotiations should unfold, recommended First Nations work out issues that concern their shared use of territory among themselves. That remains the expectation today. The treaty commission, the government-funded body set up to supervise the treaty process, says shared territory disputes "should" be resolved early in the process, before an agreement-in-principle is worked out. But it lacks the authority to ensure the policy is implemented. All it can do is push First Nations to try to reach workable agreements with neighbouring communities.

"It's a First Nations issue," Chief Commissioner Sophie Pierre told the Tyee. "First Nations have been sharing their territories since time immemorial," she said. "In the past, there have been disagreement, disputes, but they've been settled in a way that each of the First Nations have continued to exist."

Competing claims need goodwill, good process

But if the land dispute between the Stó:lō and Yale communities remains unresolved, some believe the matter will probably end up in court.

"These are very complicated, potentially legal issues," said Robert Morales, the chief negotiator for the Hul'qumi'num Treaty Group, which represents six Coast Salish First Nations located in southeastern Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands and the lower Fraser River. But the issues are also "very much wrapped up in culture and history," he added. "There needs to be a process earlier than when a [First] Nation gets to final agreement to resolve those issues."

Yale First Nation Chief Bob Hope, who hopes the federal government will ratify the treaty before Christmas, said the neighbouring Stó:lō people, some of whom fish in areas that will be included in the Yale Treaty Settlement Lands, "do nothing but waste time."

"Only now that we're so close, they've really been creating problems," he said.

The dispute between the Yale and Stó:lō is hardly the first time aboriginal groups have collided during treaty negotiations over issues of shared territory. When Cowichan Tribes disputed Tsawwassen First Nation's claim to historical aboriginal rights to fish in the Gulf Islands and along the Fraser River, the B.C. Treaty Commission provided funding to hire a mediator to help resolve the issue.

"We were able to reach an agreement on the Gulf Island area," said Eamon Gaunt, who was an assistant negotiator to the Cowichan chief at the time. "It acknowledged that Tsawwassen, when exercising treaty rights within the Gulf Islands, will seek permission from the Cowichan Tribes and Cowichan Tribes will grant that permission provided there's some certainty."

In other words, they settled on an honour system without actually sorting out the details of the exact claims.

But the shared territory issue was never fully dealt with, according to Gaunt, because an agreement over shared land claims along the much coveted Fraser River, where the Cowichan people also claim land, was never reached. "There's very little Crown land left on the Fraser River and Tsawwassen got a lot of it," he said.Gaunt says that "one of the major failures of the treaty process" is that First Nations are not required to provide evidence that the land they claim is theirs. Instead, First Nations may define their traditional territory by drawing boundaries that the treaty commission's guidelines say must be "generally recognized as being their own."

But that produces treaties that fail to fully address competing claims and it leads to issues like the ones that now face the Stó:lō and Yale. "Yale played the game and they negotiated a treaty," Gaunt said. "And government wants to see that treaty through," he added. "I don't know what the Stó:lō are going to do, but some of them are pretty upset about it."

Since the Fraser River Basin covers about one-quarter of the province's land mass, the river, including the lakes, streams, marshes, swamps and waterways that flow into it, historically provided a source of life that connected most of the First Nations in British Columbia. That means that the 98 First Nations bands located in the Fraser River Basin region have an aboriginal right to claim the land as part of their traditional territory.

Solutions lie in First Nations culture

There is a Coast Salish proverb -- uy' ye' thut ch 'u' suw ts'its'uwatul' ch -- from Hul'qumi'num elders that means "be kind and you help each other." Anthropologist Dr. Brian Thom calls it a "little nugget of wisdom" that shows how First Nations, whose societies connect through family relationships, grapple with a foreign worldview that was imposed on them when Europeans arrived in North America. The settlers brought with them a different understanding of borders and property.

Through the treaty process, First Nations are required to conform to this understanding of territory by drawing fixed lines on a map to specify the land that they claim as their own. To avoid disputes that may arise when the lines overlap, Thom says "First Nations need to continue to listen to the elders and follow their customary laws around what are proper relations with their neighbours and with their extended kin."

"The elders are telling us, 'Don't let the government divide and conquer. Don't draw boundaries, don't cut your family off. Don't forget who you are as a person.'" The focus should be on knowing your family tree and your territory, and how they both connect, Thom says. "Who you are as a fundamental citizen of your aboriginal nation -- that's a big important issue of self-determination."

It's this kind of "self-determination of citizenship" that matters most for First Nations as they work towards agreements with governments, Thom said. "And if we solve that kind of problem then these overlap things dissolve. Then we don't even use words like overlap. It's just a dirty word."

The Stó:lō people erected a prominent granite memorial in 1938 in a cemetery called I:yem, near the Fraser Canyon. Its large white cross, now greyed with age, protrudes from a solid rectangular base that towers more than twice as high as the ferns and tall grasses below. Below the cross was a plaque that read: "Erected by The Stallo Indians -- In memory of many hundreds of our forefathers buried here. This is one of six ancient cemeteries within our five mile native fishing grounds which we inherited from our ancestors. R.I.P."

The memorial marks the place where ancestral remains were reburied when the Canadian Pacific Railway was built through the region. Scholars say the memorial represented a broad claim of communal title to the canyon fishery. According to University of Saskatchewan's Dr. Keith Thor Carlson, the inscription on the plaque acknowledged that the principal threat to aboriginal fishing rights came from non-aboriginal interests. It implied that disputes between First Nations in the region "could and should be handled internally."

That continues to be the message today, Pierre told the Tyee. "For those First Nations who see a future for themselves for being self-determining and self-governing, and governments who have a commitment to reconciliation, the best and clearest way for all parties to achieve that is through a negotiated treaty."

"We need to go back to cultural ways that we handled disputes and most importantly, we need to go back to the ways of sharing the land and the resources the way that our ancestors did in order for us to survive as long as we have," Pierre said.

Francis echoes her message as he negotiates for the Tla'amin community. "Your neighbours are your allies," he told The Tyee. To him, getting permission from First Nations to harvest resources on neighbouring lands is more important than getting permission from governments.

This concludes the "Treaty Troubles" series. Find all four parts here. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: