"In the beginning, there was nothing but water and ice and a narrow strip of land."

That, Heiltsuk oral tradition has it, is how the world began. It is also how tradition records the coastal First Nation's earliest collective memory.

The Heiltsuk aren't the only inhabitants of this coastline with a long claim. The Wuikinuxv, to the south at Rivers Inlet, and to the east at Bella Coola the Nuxalk, each have their own deep histories (see below for a visit to Rivers Inlet and a video tour of Wuikinuxv carver George Johnson's workshop). To the north are Tsimshian and Haisla territories. Boundaries among their various territories are indistinct, with many areas having been used traditionally by the members of more than one of the area's First Nations.

Long one of the largest and most powerful nations in the northwest between what we now call Vancouver and Alaska, the Heiltsuk are reasserting their presence in this new century. If they -- and a growing body of science -- are to be believed, it's a presence that's been maintained on the central B.C. coast if not quite since the beginning time, then at least since the beginning of humanity's time on this continent.

That turns out to be of much more than a mere historical interest. It's an enduring connection with a more resilient past that's energized the nation's approach to everything from business ownership to its exercise of legal rights over a coastal territory half the size of Vancouver Island.

Most Heiltsuk today live in Bella Bella, a reserve community built on the gentle, forest-backed hillside overlooking a protected bay on Campbell Island, roughly half way down the coastal archipelago at a point due east from the southern tip of Haida Gwaii -- a geographic fact that may help account for the longstanding rivalry and occasional warfare waged between Haida and Heiltsuk in the past.

Today, Bella Bella is the central coast's largest town, and the only one with a hospital, expanding industry or a stable population. Bella Coola, 90 km away on the mainland and connected to the outer world by a highway, is the seat of the Regional District government that nominally serves this part of the coast. But Bella Coola's residents have been slipping away in recent years; the Regional District holds little sway.

More importantly to the Heiltsuk, Bella Bella forms a national capital of sorts to an unceded traditional territory of 16,658 square kilometres. The Heiltsuk have detailed plans for developing that territory's resources to support their 1,600 residents without, they hope, exhausting the landscape the way so many boom-and-bust ventures conceived by Euro-colonial outsiders did in the last century.

Those hopes for the future, in a community that continues to struggle with unemployment rates above 80 per cent in some seasons, rest decisively on the past however -- in ways both material and spiritual.

"Through every hardship we have endured since contact," elder and community social worker Mavis Windsor testified last July before the federal panel reviewing the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline route, at a hearing across the water on Denny Island. "We have survived only because of the resilience and integrity of our territory and our culture handed down to us through our ancestors.

"The social and mental health of our people," Windsor said, "is intrinsically tied to the health of our traditional territory, its abundance of resources and our ability to access them."

Beyond that, the Heiltsuk are staking their legal standing to share fully in the future development of a territory that begins at the mountain tops and extends out to the continental shelf, on evidence of an unbroken residency here as descendants of the first humans to set foot on this coast -- ever.

"The oral traditions speak to our continued occupancy since before the end of the last ice age," the Heiltsuk Tribal Council asserted in a formal brief to the same panel that Windsor addressed.

'We're here'

The Heiltsuk (like their neighbours, the Nuxalk) stepped away from the formal federal-provincial treaty-negotiation process shortly after it began nearly two decades ago (the Wuikinuxv remain in the process). Instead, since 1998 they have pursued a strategy that could be said to boil down to, "We're here. Live with it."

It relies on the increasing legal traction that a series of Supreme Court of Canada and lower bench rulings since the mid-1990s have given to the existence of aboriginal rights and title. In common with some other First Nations, the Heiltsuk are betting that the law's expanding definition of their inherent rights to those 16,000 sq. km can deliver them more benefits, sooner, than the sclerotic and glacial treaty process.

They have already been on the right side of one of those decisions. In R v Gladstone, a landmark ruling in 2005, the Supreme Court of Canada overturned the convictions of Bella Bella brothers William and Donald Gladstone under the federal Fisheries Act for offering to sell herring roe (spawn on kelp, or 'SOK') to a commercial buyer in the Lower Mainland. The court found that the Gladstones had a right to harvest spawn on kelp that predated the Act, and the regulations under which they were charged, and Canada itself.

It was a precedent-setting decision in Canadian aboriginal law. It's also what makes the herring 'SOK' fishery that my colleague Jude Isabella witnessed and described in a story published on Monday more than just an evocative exercise in personal communion with culture and identity for the Heiltsuk, let alone a welcome source of a savoury delicacy.

Presence is proof

An earlier Supreme Court ruling had laid out exactly what aboriginal groups needed to do in order to establish material legal rights like the one the Gladstones exercised over all of their traditional territory. It amounted, the court explained in its decision in Delgamu'ukw v The Queen,, a case launched by two other northwestern B.C. nations, the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en, to a multi-part test.

First, as a legal analysis by the Blake Cassels law firm distilled it, "the land must have been occupied prior to European sovereignty." Secondly, "there must be continuity between present and pre-sovereignty occupation."

In plain English, a group claiming aboriginal title to a landscape has to prove that its direct ancestors used that landscape before Europeans arrived (in the case of the Central Coast, deemed to be 1846) -- and that they themselves continue to use it for the same purposes.

Thanks to Gladstone and Delgamu'ukw, setting hanging kelp for herring to spawn went from a relatively simply act of harvesting a richly productive marine landscape, to a symbolic act laden with implications for the Heiltsuk's proprietary and political interests. Every link with the past became an item of evidence to help secure the community's territorial and economic future.

Since shortly after Delgamu'ukw, the Heiltsuk have been methodically assembling their body of proof.

The campaign to prove that the Heiltsuk have occupied these coastal islands and inlets since human time began on this continent is headquartered in a low, green-roofed log building to one side of Bella Bella's municipal services yard, overlooked by a telecommunications tower where bald eagles perch. This houses the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department [Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department] (HIRMD). Its mandate is considerably larger than documenting the Heiltsuk presence here (as I'll get into tomorrow), but that presence provides the grounds for all the rest of its work.

Mapping the evidence

The campaign's general is a deceptively slight woman in her late 60s, whose quiet voice and subdued dress suggest the stereotype of an unworldly librarian. Jennifer Carpenter, the U.S.-born, University of British Columbia-trained anthropologist who is HIRMD's culture and heritage manager, is renowned rather for a will of steel.

Agreements between the Heiltsuk and the province have confirmed the First Nation's right to decide who gets to do intrusive research on its territory -- things like digging into middens, and other activities essential to the kind of research we reported on earlier in this series. Carpenter, a widow and grandmother who "married into the community," as she says, in the 1970s, has made sure their research aligns with the Heiltsuk's interest in documenting their indigenous provenance.

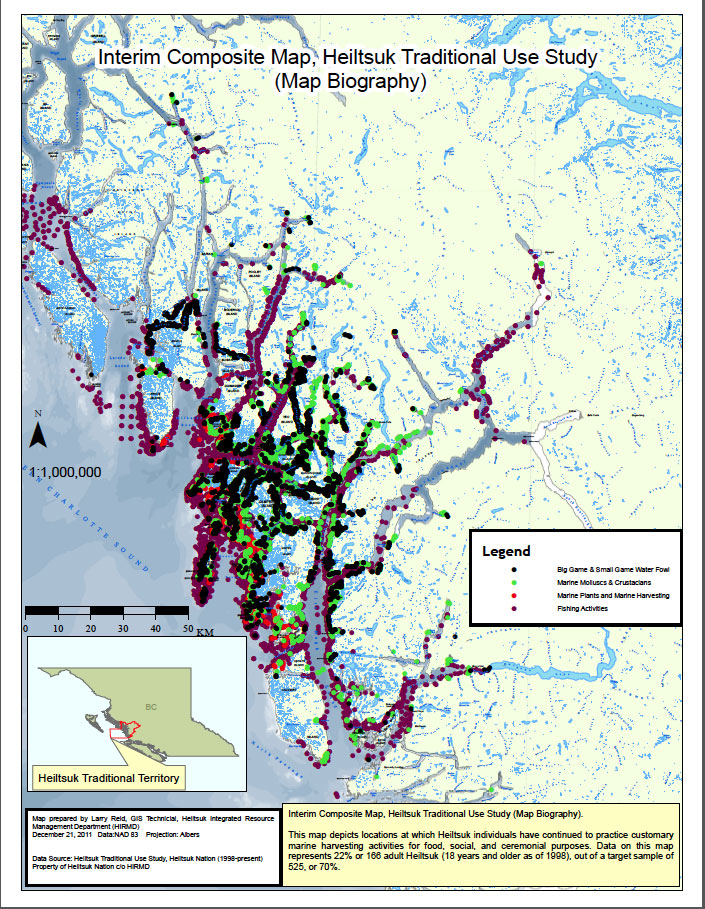

HIRMD has also been asking Bella Bella's own citizens to provide what Carpenter calls "living proof": testimony to a specific instance of use of some part of the nation's traditional territory for a distinct and identifiable purpose grounded in family harvesting rights within Heiltsuk tradition. HIRMD, she explains, asks people to voluntarily record, "the actual places on the land where you caught something, or shot something or picked something and took it home to feed your family."

HIRMD's goal is to record the experiences of 70 per cent of the nation's adults. So far it has managed to get those of only slightly more than 20 per cent. But the results are already impressive.

A map, dotted in purple, green, red and black to indicate where individual contemporary Heiltsuk have taken big or small game, shellfish, marine plants, or fish, splashes the coastline in colour from the bottom end of Fitz Hugh Sound north to the Kitimat shipping approaches through Douglas Channel.

Instances of living links with the past are everywhere, from fishing spots at the mouth of Kwakshua Channel, to collecting shellfish and herring spawn in Kwakume Inlet or gathering seaweed from the rocky islets exposed to the bluster of the open Pacific.

Archaeological research, often tracking clues in Heiltsuk oral history, has expanded the inventory of resource practices employed on the coast in the eons before European contact. It was a working shoreline, Carpenter says, where fish were trapped at the mouths of streams and sorted so that the best animals could be freed to reproduce, and only modest numbers of the more mediocre taken home for food. Rocks were realigned, she adds, to create 'gardens' hospitable to clams: "That was a substantial form of shellfish aquaculture."

Burning the 'bridge theory'

As my colleague Jude Isabella reported earlier, such discoveries are persuading academics to rethink the settled account of how humanity first arrived on this continent. The old idea was, in brief, that people migrated from Asia along coastlines exposed when much more of the world's water than today was locked in ice sheets, passing the coast's mountain walls either in boats or walking a "narrow strip of land" now under Queen Charlotte Sound, but always moving on to more hospitable climes further south.

The emerging view is perhaps more in keeping with human nature: that at least some people got this far, recognized a great place to live off a generous land, sea and shore, and looked no further.

Artifacts of human use recovered at Namu have been carbon dated to 9,700 years ago, a time not so very long after when other research indicates the great ice sheets retreated from the coast for the last time. But were those people also these?

The Heiltsuk certainly think so. "Does our history just go back 10,000 years?" Carpenter answers her own question with an elder's observation recorded over a century ago by German-American anthropologist Franz Boas: "'In the beginning, there was nothing but water and ice and a narrow strip of shoreline'," she quotes. "So our oral traditions begin to capture the fact that people were living in this area before the end of the Ice Age."

Science is less certain. Some artifacts recovered at Calvert Island are likely early Holocene tools, much like tools from other coastal sites, like Namu, that date back nearly ten millennia. To trace a direct lineage from those ancient toolmakers to contemporary Bella Bellans is more difficult. But neither have archaeologists turned up any evidence that invasions from beyond the region ever brought entirely new people to the coast, at least until Europeans arrived.

Carpenter fears that the effort to explore and document the past may be working against the clock in the present. Appearing after Mavis Windsor before the federal pipeline review panel in July, she told its members that, "Oil spills can destroy the ability to carbon date. It introduces another form of carbon, and carbon dating is the key tool that's used to identify how old a site is and how long it's been used."

A spill of Asia-bound diluted bitumen, during its passage down Douglas Channel or through the offshore waters the Heiltsuk claim, she fears, could destroy the very evidence on which that claim is based.

It's not the only way a spill could threaten the past as well as the future. A bigger impact on archaeology further north from the region's last big spill, the Exxon Valdez grounding in 1989, was vandalism. Many wooden artifacts from soiled sites were preserved because they were saturated with water. But crews brought in to clean up the mess -- thousands of people looking for short-term work and quick money -- meant that important sites were often destroyed inadvertently. In one case, a spill worker who stumbled onto a burial site stole and took home a skull.

(Read more about the Exxon Valdez's impact on native communities in the first-person account of Port Graham, Alaska, Chief Walter Meganack.)

A future built on the past

Mavis Windsor began her remarks to July's public hearing by recalling her lineage: the Heiltsuk name given her by her maternal grandmother; the copper raven, two-finned killer whale and eagle crests to which clan roots entitle her.

The recitation was more than a gracious nod to her parents and grandparents though. In a culture of oral traditions, of rights to harvest resources that follow the lines of family, and with a strong desire to preserve the wisdom of the past into the future, it was a statement of claim and enduring presence as much as one of identity.

That today's residents of Bella Bella could be direct descendants in unbroken line from the first North Americans is certainly remarkable. The very idea evokes a sense of almost breathtaking intimacy with one of mankind's pivotal moments -- the first human colonization of the land-masses only very much later to be called the Americas. Shake hands with history!

But while being descended from North America's very first settlers, and arguably among its most long-settled ones, would convey an unmistakable distinction, it's not really necessary to meet the tests of Delgamu'ukw (use only has to be established before 1846 for that), and it probably isn't much direct help in getting Bella Bella's unemployment rate down.

Yet the long, richly connected story that the Heiltsuk have shared with this landscape has nonetheless turned out to be a powerful asset as the nation rebuilds.

"As a people," Windsor told her panel audience, "we have seen how the loss of our resources has eroded our family teachings, our traditions and our values." Now, she said, the Bella Bella community is taking steps to "revitalize our traditional customs and family values... that promote a strong sense of Heiltsuk identity."

Those steps are paying off, as I'll report tomorrow in the concluding episode of this series on the enduring coast.

Yesterday the "BC's Enduring Central Coast" series dropped you into the midst of Hakai Beach research institute and into the mind of founder Eric Peterson, and offered a timeline of the region dating back to before the first Europeans arrived.

Tomorrow: From carbon sinks to high-tech fish plants: Exploring ways of developing the coast while safeguarding its natural treasure.

The entire multi-part series is collected here as each part is published this week. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: