The task of assessing whether any given research project is "ethical" is a complicated one that preoccupies many philosophers, scientists and researchers. But in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside (DTES), those doing the debating aren't your usual suspects.

They're called the NAOMI Patients Association (NPA), and they've been meeting each Saturday since Jan. 2011 to discuss the benefits and ethical problems of their participation in NAOMI, a heroin-assisted therapy study, more than five years ago.

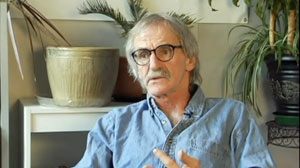

Dave Murray, a recovering heroin user with a 35-year-old addiction and a well-groomed white mustache, founded the NPA through word of mouth after a long struggle to go clean. "We wanted to see how everyone was doing. When you do research, you have to make sure it doesn't harm people, and you won't know if you don't follow up."

Composed of a rotating cast of 44 former and current drug users, the NPA's mission is to provide a peer-based support network and to serve as an advisory board for future addiction studies. Ultimately, its goal is "to have alternative and permanent public treatments and programs [for addicts], including heroin assistance programs."

On March 31, the NPA published the result of a year's work: a 37-page report dubbed "NAOMI Research Survivors: Experiences and Recommendations." Written with the help of Susan Boyd, a professor in the Studies in Policy and Practice program at the University of Victoria, the report details the research participants' experiences during NAOMI and provides ethical recommendations for researchers working on future addiction studies in the DTES.

The crux of their report is this: having access to heroin-assisted treatment changed their lives -- but the study's sudden termination left them all reeling.

"All the stress in our lives disappeared. We were healthier; we weren't resorting to criminal activity to get the drug. The quality of our lives was just so much better," says Dave Murray, the NPA founder.

Then, as suddenly as this new treatment option arrived, it was taken away. After a 12-month trial on medically prescribed heroin, research participants were only offered methadone or buprenorphine to treat their addiction -- even though the study specifically sought out addicts who had failed at these traditional therapies at least twice before. In Canada, these are the only two treatment options currently available to opiate users.

NAOMI researchers applied to Health Canada for the compassionate use of heroin for the participants who responded well to treatment, but in 2007 Health Canada formally disallowed the request.

"We're the only people in the world who were treated this way," says Murray.

The NAOMI study isn't unique; heroin-assisted therapy studies have been completed in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Spain, England, Germany and Belgium. What is unique is the treatment of the study subjects after the fact.

In all these countries, the study participants were allowed continued access to heroin-maintenance therapy on a compassionate basis -- even if the country’s health policies didn't change.

"An ideal study -- if it's proven successful in terms of social, health indicators and criminality -- should be morphed into the health care program," says Murray, "At the very least, it should be adopted for the people who participated in it."

The issue of consent

There is no simple answer to the question of what makes a human research trial ethical, but one of the reoccurring themes is whether or not the study subjects are capable of providing free and informed consent.

This is an issue even the NPA members struggled with after the fact.

The NPA report affirms that NAOMI's researchers warned the participants from the get-go that their treatment would only be temporary. They made no long-term promises. "I went there with the full understanding it was a study. It was a study," says one anonymous female NPA member (all the comments in the NPA report were made anonymously).

Others say consent was problematic since the researchers controlled the very drug that dominated their lives: "Our life depends on this drug and here we're offered this drug," says one male NPA member, "I would sign anything at that point. I would probably say which finger do you want, you know, or which arm do you want?"

Originally from Spain, Dr. Eugenia Oviedo-Joekes worked on Spain's heroin-assisted therapy study before joining the NAOMI team as a co-investigator in 2007. She's had a chance to sit down with NPA members.

In the case of NAOMI, Dr. Oviedo-Joekes emphasizes that consent wasn't merely established with the signing of a form, but through a long conversation between the researchers and the study participants.

"Almost 90 per cent of the effort of the ethics board is put in your consent form," says Oviedo-Joekes. "Before they sign the consent form we ask them certain questions to make sure they get the key points. We would ask them: 'Do you understand that after six to 12 months we cannot provide you with the study medications?'"

Despite the efforts of researchers to establish valid consent, Oviedo-Joekes is aware of the shortcomings they're bound to encounter when dealing with pain management or addiction research.

"I suffer from chronic headaches. I have tried holistic treatment, traditional treatment, yoga, everything. I still get headaches. If somebody came up to me and said, 'Hey, we're doing this clinical trial to cure chronic headaches.' I would skip the consent form. I would say, 'Where do I sign to get six months free of headaches?' I don't care if it's temporary. Do you think I'm capable of giving consent? Yes, I think I am. Am I vulnerable? Absolutely," she says.

For Dr. Martin Schechter, NAOMI's principal investigator and a professor and director at the University of British Columbia's School of Population and Public Health, the notion that people living with addictions cannot provide consent is unacceptable.

"This is actually something that I find offensive. I think it's paternalistic and demeaning," he says. "If you follow that argument, then someone who is dying of cancer and is so desperate to find a cure is not qualified to provide consent. Well then we couldn't research cancer. It just doesn't make sense."

A proper exit

Much like its European predecessors, the NAOMI trials were to many minds a success. On Oct. 7, 2008 Dr. Schechter announced, "We now have evidence to show that heroin-assisted therapy is a safe and effective treatment for people with chronic heroin addiction who have not benefited from previous treatments.”

When you're dealing with 251 addicts in Vancouver and Montreal who each have at minimum a five-year-old habit, success looks like this: illicit heroin use fell by almost 70 per cent; the proportion of participants involved in illegal activity fell by half, and the retention rate was high. Of those in the control group who received oral methadone, only 54 per cent stayed through the 12-month treatment. An astounding 88 per cent, however, stayed the course when receiving heroin-assisted therapy.

"Society had basically written them off as impossible to treat," said Dr. Schechter, "but NAOMI proved that they could be helped."

Despite the results, when the 12-month trial was over, the NAOMI researchers could only offer the study subjects complete detox, methadone maintenance or buprenorphine, traditional treatments the study participants had each already failed at least twice before.

Considering the global success rate of heroin-assisted therapy studies abroad, NPA's report says that NAOMI should have had a more effective exit strategy in place for the study participants.

"I think the thing that's flawed in this, in the ethics, was the ethics approval, like, for them to approve this study without full -- I mean, without having an exit strategy in place that was doable,” says one anonymous female NPA participant.

"There's been these kinds of studies done in other countries before us. So they had a good idea of what the results were going to be. And to go into that without having a way out that worked for the client or the participant, I think that was the -- that’s the thing that wasn't right, in my opinion," she says.

When NAOMI received ethical approval from the University of British Columbia, the Université de Montreal, the University of Toronto and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada's premier health research funding agency, the decision was not made lightly. The idea of NAOMI was first conceived in 1998 and it took seven years for the researchers to jump through all the necessary legal, ethical and logistical hoops before recruitment began in 2005.

"We were asked many questions," says Dr. Schechter. "One of the fundamental questions was of course whether we would be able to offer the therapy at the end of the trial. Those kinds of decisions were in the hands of the health policy makers, not the researchers. We were committed to helping convince them, but we could not guarantee that, and that was made clear in the consent form."

Ultimately, Dr. Schechter says they "tried everything" they could to keep the treatment going: "We took the evidence from the study and we went to the then-CEO of Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) in a private session. We showed the evidence and said we believed very strongly that they should continue the therapy as part of treatment. We were told they didn't have enough money and they couldn't do that."

Anna-Marie D'Angelo, the senior media relations officer at VCH says Dr. Schechter did approach their CEO. "As the end of the NAOMI research project neared, two options were considered: the continued operation of the clinic as a methadone program and the continuation of injection medication on compassionate access basis. The case for compassionate access was denied by Health Canada's Special Access Program.

"As a result, the NAOMI study concluded in June 2008 with all subjects who received injection medication encouraged to switch to a newly funded Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) program."

On March 15 of this year, a new economic analysis of NAOMI's findings showed that heroin treatment is not only more success than methadone for some chronic users -- it's also more cost effective. Health policy makers have yet to budge.

"I can tell you there is no shortage of economic studies that come out and are routinely ignored," says Dr. Schechter. "In the end there's a couple things going on: one is that the authorities say they don't have enough money, and then there's the issue that this research is not exactly non-controversial. There are politics."

In response to the NPA report, Dr. Schechter is regretful: "In terms of the NPA and those folks, I completely understand how they feel like they have been screwed by the system, and the researchers they see as part of that system."

SALOME, a new frontier

Despite stunted policy changes, the NPA is already influencing research -- to a point.

In the past year, Murray and the NPA have discussed their suggestions with those working on the Study to Assess Longer-term Opiate Medication Effectiveness (SALOME), a follow-up study to NAOMI.

The new study, which started recruitment in January, is testing the effectiveness of hydromorphone, a licensed pain medication, to see if it is as effective as heroin-assisted therapy in benefiting those living with chronic opiate addictions.

It is the first study of its kind, anywhere in the world.

"Because Canadian law isn't ready to accept medially prescribed heroin, we thought it would be good to have a test with this licensed medication," says Oviedo-Joekes, one of SALOME's two principle investigators. "We hope that there is more acceptance of hydromorphone as a form of treatment. Will it be easier? I don't know, you never know how the public and policy makers will react to the results."

The researchers are consulting with the NPA and with an independent community advisory board, but the NPA report says not enough has been done to accommodate their suggestions: "In the pursuit of scientific evidence, important issues and recommendations by the NPA and VANDU about consent, ethics, peer support and human rights have mostly been ignored. The SALOME study also has no exit strategy in place for its participants. Thus history may again repeat itself in Canada."

The future: A holistic approach

Despite the ethical challenges surrounding addiction research in the DTES Dave Murray doesn't want to stop it all together. "I applaud them for at least trying something different," he says.

Over a cup of coffee at the Woodward's building, his new home, Murray dreams of an addictions research model that replaces a strict scientific approach with a more human one.

The root cause of addiction isn't just a bad drug habit, says Murray. It's social isolation, and to deal with that we need a more holistic approach to treatment that goes beyond drug substitution. "They figure it would mess with the research," he says "but it would be a more humane way of doing things."

For Murray the scientific validity of a study is irrelevant if the patients aren't being helped.

"I think if the end goal is abstinence, then you need to take the stress out of their lives and get them back integrated into society," he says. "That's why we need to look at a more comprehensive way to improve people's lives." ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: