When the time came for Canada Place to strip off its iconic white sails and replace them with new ones, the federal government suddenly had 14,500 kilograms of Teflon-coated fibreglass to get rid of. Did anyone with a neat recycling idea want the stuff?

Linus Lam did. So Stephen Harper handed it over to him.

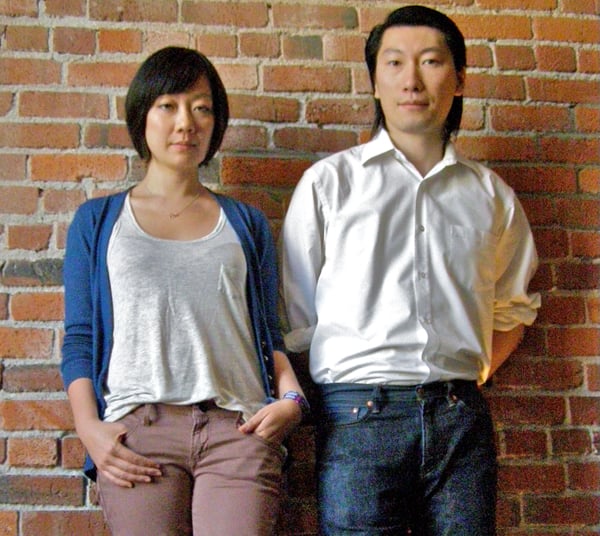

Lam, 35, is the executive director of the Vancouver chapter of Architecture For Humanity, a San Francisco-based not-for-profit founded in response to the Kosovo refugee crisis in the late '90s. Today, all over the world, thousands of architects and designers donate time and skill to AFH in an effort to find architectural solutions to humanitarian issues.

It's a practice that some people call humanitarian architecture, though it's more commonly known as social architecture or architecture for public good.

Lam doesn't much care what you call it, as long as it addresses some of the critical issues in Vancouver, whether that be preservation of community heritage through neighbourhood revitalization projects, or solving homelessness through social housing projects.

In the two and a half years it's been around, AFH Vancouver has been busy. It's hosted design competitions and exhibitions (including Prefab 20*20 at IDSwest in 2009), and has partnered with local arts and youth organizations in an effort to engage the wider community in a conversation about design. Last year, it caught the attention of city hall, which, inspired by one AFH-led competition -- the Quick Homes Super Challenge -- began looking at pre-fab solutions to shelter Vancouver's hardest-to-house.

Then, in February, Prime Minister Harper held a press conference in Vancouver to announce that AFH was inheriting Canada Place's iconic roof. Though some of the material will be used for projects with United We Can and SOLEfood, and a pile of it has already been sent to East Africa with a group of BCIT students, Lam recognized a wider creative potential. He put a call out to international organizations, asked them to send him pitches. He's already received dozens.

Out of surburbia

Lam is slight, in tidy but lived-in clothes, and thick black hair that looks a bit windblown. Though he has a quick sense of humour, he has a slow, thoughtful way of speaking, of thinking aloud. Sometimes he gets lost in his words, forgets the question. He's worried he'll sound boring on tape.

He tells me how envious he is of journalists, of how much energy we seem to have. This seems odd. In addition to AFH, Lam is a partner in his own small firm, and runs an online magazine. He also works part-time for the Architectural Institute of British Columbia. An hour into our interview, I ask him if he's got any final thoughts to add to our discussion. He says he never has final thoughts.

The Lams immigrated to Canada from Hong Kong in 1988, and settled in Port Coquitlam. Linus was 12 at the time, an only child. It was a good fit for the family, he says, especially for his parents, who still live there, "now fully suburbanized."

Lam discovered design as a teenager, inspired by a special issue of Architectural Digest that featured the work of 100 architects from all over the world, including the master Japanese architect Tadao Ando, a minimalist who works largely with concrete. Though he was too young to understand Ando's work and the context in which his buildings were placed, something about Ando's designs caught Lam's artistic imagination. So much so that, 20 years later, he still has the issue.

"True story. I just loved it. It was a little bit of art, and a little bit of science."

At the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, pursuing a degree in Environmental Design Studies, Lam was mentored by the great Canadian architect Gustavo Da Roza, who took him on as an intern. After moving to Vancouver with his romantic and creative partner Denise Liu, Lam found another acclaimed mentor, modernist architect Peter Cardew, who runs a small practice that relies heavily on a hand-drawing design process -- a rarity these days, when most firms rely on computers.

For a time after that, Lam and Liu worked together at IBI, an international firm with over 2,000 staff. When the two decided they were ready to launch their own firm, Edison & Sprinkles was born. "And that's when I started to work non-stop," says Lam.

For almost two years, Lam continued to work days for IBI, and in the evenings took on projects as co-design director for Edison & Sprinkles. When he finally left IBI last year, it wasn't to rest.

'Propelling the city to a better place'

A quick survey of Edison & Sprinkles designs reveals a modern, west coast aesthetic, rich in materials like wood and steel and concrete, with clean lines and care of detail. There's a whimsy to their interiors as well, all bright and airy, colourful at times too, but never busy or overwhelming. Even in the smallest spaces, there's both intimacy and lightness.

Lam and Liu have amassed an impressive list of projects. There are restaurants (Lumiere, Joey's Bentall One, Goldfish Pacific Kitchen) and a clothing shop (TNA Metrotown), houses (Shannon House, Kirkness House) and loft conversions (Music Styling). There are institutional projects and exhibition projects and cultural projects.

And then there are the labours of love.

Lam and Liu first came across Architecture For Humanity while still in school, when headquarters launched a competition to design mobile AIDS clinics for Africa. The two entered, and their design (picture a sleek truck-bed camper as clinic, taller than it is wide, with moveable parts and large windows on every side) made it through to the final round -- beating out thousands of entries from all over the world -- and became part of an awareness-raising exhibition that toured North America in 2002.

Over the next several years, Lam kept abreast of the organization's activities and steady growth, and was finally inspired to launch a Vancouver chapter of Architecture For Humanity out of a sense of responsibility to put his skills to use for the greater good of his community.

"I genuinely believe that people that are attracted to this profession, they like to see change," he says. "They like to see, through their design effort, that they can propel their city to a better, more progressive place."

By the end of 2009, running Architecture For Humanity was part-time job. As a way of meeting new friends and getting to know the local scene, Lam and Liu had also launched something called Artsy Dartsy -- an online guide to the city's art events -- shortly after their arrival in Vancouver. For a year, they built a new website from scratch every week. ("It sounds crazy, I know," says Lam.) It featured all the city's shows and openings, and the community loved it.

"We wanted to recreate the sense of community we'd had in Winnipeg -- vibrant, active, intimate," says Lam. It worked. As the site got more and more traffic, people came to expect more content. Lam and Lui happily obliged, and today, Artsy Dartsy is the go-to place for all things art-and design-related.

Steven Cox is a founding principal and creative director of Cause+Affect, a local design and consulting firm, and curator of Vancouver's increasingly popular Pecha Kucha Night. Cox came through UM's architecture program a couple of years ahead of Lam, and in recent years the two have done the occasional event together -- including a special Pecha Kucha to raise money for AFH's Japan tsunami relief efforts. They have talked about someday, perhaps, opening a design centre together.

When I ask Cox about what kind of impression Lam's Architecture For Humanity efforts might leave on the local design scene, he suggests I widen my lens a bit.

"AFH is getting there. Give him time and it will take off. But it's a tough business, and people need encouragement to get involved. He could probably use some help. Linus is most interesting when he's working where architecture and art blend. He has a million and one things on the go at a time -- things that make Vancouver an interesting city. And one of those things is Artsy Dartsy, which I would argue is making the bigger impact."

To Lam, it's all the same. He's not so much interested in growth or milestones as he is in the success of each individual project, no matter how small. And he measures that success by the level of community engagement. It's about having conversations, he says, and using design to provoke and inspire.

Hectic summer

To that end, AFH initiatives will keep rolling forward. Top of the list is a small but significant intervention -- the restoration of the façade of an historic building in Chinatown. It's taken years of negotiation with the City and the neighbourhood to realize. When it's done, it will be the chapter's first permanent physical presence in Vancouver.

The old Canada Place sails will be put to use, metre by metre. Though Lam can't talk about the pitches he's received until they're awarded the material, there is the BCIT-led construction of a children's centre underway in Tanzania. Closer to home, the material has made its way into the hands of a few local designers for experimentation, and, pending funding, SOLEfood is working with AFH on a design for portable urban farms. There's also a plan in the works to build a temporary home for the Downtown Eastside bottle depot, United We Can.

With all of that in addition to Edison & Sprinkles' ongoing design work -- including a laneway cabin and a couple of houses -- an IDSwest 2011 FutureMasters exhibition to curate, the Artsy Dartsy content monster to feed, and whatever challenges Lam can dream up for his colleagues, the designer isn't having much time off this summer.

"Everything that I've seen through my non-profit work, through my professional work, through my labours of love, it has encouraged me. I'm frustrated that I don't have more time in the day because there's just so much to do, so much that we could do," he says.

And then, with a shrug: "So it's not a very profitable practice. For us, it's something that feels right. We work multiple jobs so that we can sustain our permanent hobby of design." ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: