[Editor's note: This is the fifth of eight excerpts from Patrick Condon's new book Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post Carbon World. This series, running Wednesdays and Thursdays for four weeks, offers just a sampling of Condon's vital guide for green planning; interested readers are encouraged to seek out the book.]

Private car use is responsible for an increasing share of total U.S. and Canadian greenhouse gas production. Short of an immediate increase in fleet efficiency (not possible) or a dramatic breakthrough in battery technology (not likely), this share is likely to continue its climb for years to come.

Even if a zero-GHG electric auto that could travel long distances were widely available, the resources required to continue to build more than 60 million personal autos a year -- autos that last less than 10 years on average -- would drain the planet, not to mention the cost and consequences of adding at least another 25 per cent per capita of electric power to fuel such an electric fleet.

And, when a full assessment of the GHG consequences of not just the automobile use but its manufacture; the concrete used for its roadways; and the mining, processing and distribution of materials and petroleum is included, the true GHG costs are significantly higher than direct tailpipe emissions.

There was a time in the United States and Canada when jobs and homes were much closer together. With transportation distances constrained by walking distances and, later, by the reach of the streetcar, there was no alternative.

Early North American jobs and housing patterns were not unlike those of Venice, Italy, where each neighbourhood was dominated by a trade or a "guild" of craftsmen who lived and worked sometimes within the same building but always within a two-minute walk distance.

Later in England, during the height of the Industrial Revolution, complete industrial communities were planned and built -- notably Port Sunlight near Liverpool, the city organized around Lever Corporation's giant factory.

Human scale industrial communities

This same intimate relationship between living and working was imported to industrial North America, most famously in Lowell, Mass., an industrial city on the Merrimack River. Lowell was built all at one time to include industrial, commercial, civic, religious and residential spaces.

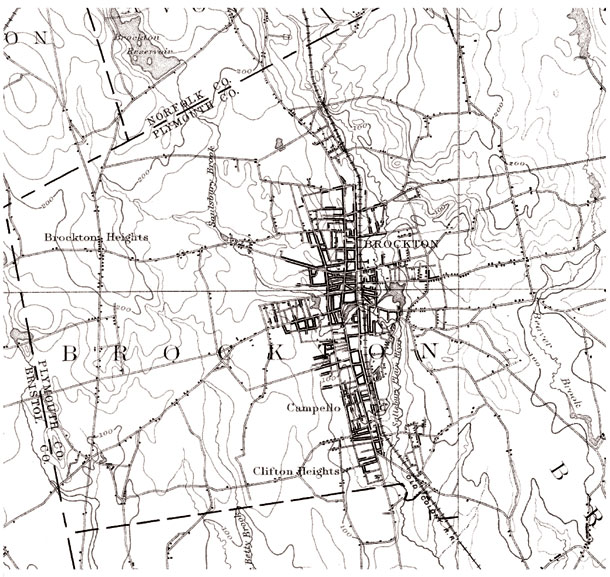

Lowell and other planned North American industrial communities have been extensively studied, but there are other, less formally planned industrial communities that had the same characteristics. Brockton, Mass., the author's hometown, is one of many eastern U.S. examples, where commercial, residential and industrial spaces organically organized themselves within easy walking and streetcar distance.

In Brockton, literally hundreds of workshops and factories profited by providing various parts of the chain of materials and machinery necessary to make shoes. These shops ranged from small tool-and-die machine shops with just a few workers to medium-sized tanneries to large shoe last manufacturers to massive shoe factories employing thousands.

Within the city, there existed an entire capitalist ecology, with shops and factories competing with one another to supply the larger manufacturers, while the larger manufacturers competed on the continental scale via a new coast-to-coast rail network.

This intimate industrial and community ecology was broken with the end of the Second World War and the subsequent construction of the interstate highway system.

The economic logic of industrial ecologies such as those found in Brockton was undercut, first by the accessibility to the bigger factories of previously remote suppliers, suddenly brought closer by trucks moving rapidly across the continental landscape. It was undercut even further by the national, and then international, trend toward an industrial economy no longer tethered to adjacency efficiencies, which ultimately bankrupted even the largest domestic apparel manufacturers in the rest of the United States and Canada.

Now in Brockton, as in other such cities, virtually none of the industry that built this once thriving city still operates (Brockton's last shoe company closed in 2009).

A landscape transformed

[After the Second World War, the construction of the interstate and provincial freeways in the United States and Canada led to an urban landscape that was utterly transformed. Any point in the entire region could be accessed from any other point in the region by car if the commuter was willing to drive up to an hour -- at least, that is, until the inevitable increase in vehicle miles travelled per capita overwhelmed the capacity of even this bloated system.

[With the right policy and financial supports, however, it is possible to have good jobs near affordable homes, reducing the need for such commutes.]

What would be the rules to guide such a regional and municipal planning effort? Proposed below are some well-precedented rules for new job site development.

Rule 1: Recognize that most new jobs don't smell bad

Over the past five decades, U.S. and Canadian heavy manufacturing job growth has slowed to a crawl, with the auto industry only the latest casualty. One might argue that such a trend is unsustainable, requiring as it does the outsourcing of the manufacture of almost all of our material goods to foreign lands.

Whatever the long-term trend, it is certain that this trend will likely continue for a number of decades, the same decades within which the retrofit of metropolitan areas must be set in motion. In the 1990s, the Portland region saw manufacturing jobs rise by just 14 per cent while nonmanufacturing jobs rose by almost 40 per cent.

The future looks even bleaker for manufacturing jobs. Between 1990 and 2010, Portland area manufacturing jobs are expected to drop 6.3 per cent while nonmanufacturing jobs are expected to increase by 54.6 per cent.

All of these nonmanufacturing job types can be fit into a community without threat of excessive noise, smoke or pollution.

This is a critical point because, throughout the United States and Canada, zoning codes have been based on the premise that the majority of "industrial" zoned job sites should be segregated from other zones, confined to isolated areas usually close to freeways but to nothing else.

This zoning habit has not caught up with the changing nature of jobs. Smelly, dangerous, noisy and industrial-scale jobs, the ones that really require industrial zones, are increasingly rare. Most of the new jobs are clean, quiet, safe and can easily fit on the second and higher floors of buildings close to streetcar city arterials.

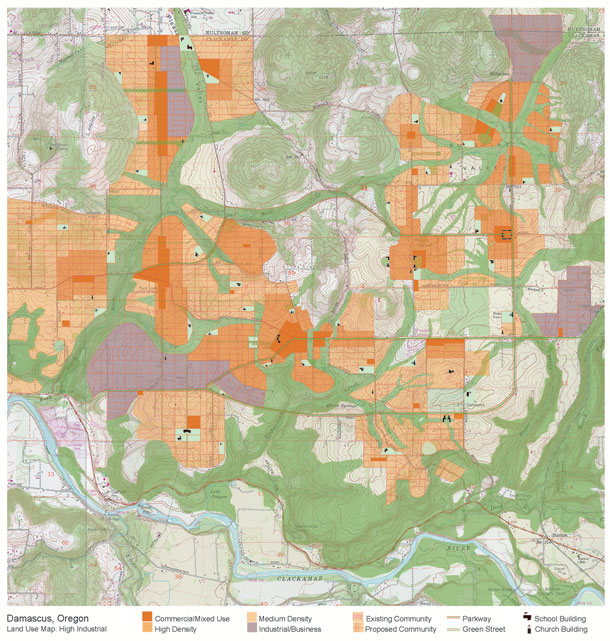

Roads to Damascus The plan for the Damascus area near Portland, Ore., demonstrates this principle.

This plan was produced at a collaborative, multi-stakeholder charrette, held to explore how it might be possible to add 100,000 people to an 18,000-acre urban area expansion and at the same time protect the site's ecology, provide alternatives to the car and create job opportunities close to homes.

This 2002 initiative took place in a region where a robust suite of policy tools provided a sophisticated planning context.

Not the least of these policy tools was Portland Metro planning district's well-known Portland 2040 Plan, a plan that for the first time identified the regional potential for jobs in both corridors and multi-use nodes.

In conformance with these general guidelines, the resulting Damascus Area Design Workshop plan found jobs space for 100,000 new jobs, enough for every worker in the district and more -- the excess intended for residents in adjoining parts of Clackamas County.

Embedded jobs

The Design Workshop instructions assumed that 15 per cent of all new jobs for the district would be in manufacturing. Those jobs were allocated to more isolated sites. But the other 85 per cent of all jobs were service, light assembly, financial, education, health care, commercial, government and other job types that do not need to be isolated.

In fact, they should be as deeply embedded into the hearts of mixed-use communities as possible to ensure synergies with housing and transit. The Damascus plan illustrates how these 85,000 jobs were accommodated along the streetcar arterials and adjacent urban blocks of the plan.

The pattern of jobs/housing integration demonstrated in the Damascus plan is not new; prior to 1950, it was the rule rather than the exception. At that time, most jobs -- even many types of manufacturing -- were knit into the fabric of the city.

Absent a gradual return to this historic pattern, it is difficult to imagine a region where access to jobs without a car is even possible. But with such integration, we may have a chance.

Rule 2: Discourage job-site space pigs

After 1950, as jobs moved out of urban blocks and away from streetcar arterials to isolated sites, the density of jobs per acre on those sites also declined. Multi-storey manufacture, warehouse and distribution facilities went out of style in auto-oriented sprawl.

One-storey buildings for all uses became the rule. Since everyone now had to drive to work, overly large parking lots consumed a large percentage of job sites. Required landscape buffers, a well-intentioned attempt to beautify new job-site areas, had the unintended consequence of making the jobs-to-acres ratio even lower.

For these and other reasons, the density of jobs per acre was reduced by over 80 per cent in just a few decades.

In the Damascus study, an average job density of 15 to 20 jobs per acre was eventually set. This was considered an aggressive target, as it is about twice as high as many conventional job-site planners assume and higher than the ambitious goals set by the 2040 Plan.

This number, while representing progress in increasing job density on sites, is still influenced by sprawl land use assumptions. This becomes absurdly obvious when you consider that general industrial and "tech flex" jobs require only 500 square feet of interior space per job on average.

If such a building covered 100 per cent of its site, even at one storey it would provide 800 jobs per acre! A more suitable jobs density appropriate to the GHG crisis we find ourselves in would be that of the more recent City of North Vancouver carbon neutral plan that calls for 1.5 jobs per dwelling unit.

Rule 3: Link jobs to streetcar arterials

New job sites rarely link to transit. In rare cases, transit comes out to meet the more mature "edge city" jobs centres, as in current proposals to tie Tyson's Corner, Va., into Washington's rapid transit system, known as Metro.

But providing this kind of retrofit after the fact can only partially succeed, and it comes at a monumental cost per worker served.

In certain cases, enlightened corporations, with the assistance of local authorities, have successfully linked mixed-use job sites to regional transit systems, as in the case of the Atlantic Station in Atlanta. These laudable efforts are the harbingers of a new opportunity, but one that must be systematized.

A regional system of streetcar arterials close to all districts, where the 85 per cent of jobs that are non-polluting could be located advantageously, is the next step. Existing and new state and provincial policy can and must mandate that municipalities zone mixed-use job sites near streetcar city-type transit corridors, within an interconnected street network, rather than at freeway interchanges.

If an interconnected street system and the streetcar city pattern discussed earlier have been hopelessly compromised, then jobs must at the very least be accessible by bus. Unfortunately, the configuration of most new job sites makes them extremely difficult to serve by bus or any other kind of public transit.

They are not on the way to anything else, and their circuitous interior road configurations doom bus drivers to long, winding trips to serve only a small handful of riders. Even in the otherwise vanguard Portland metro area, the political attraction of such job sites has rendered any other consideration moot (as shown below, at the junction of Sunset Highway and Northwest Cornelius Pass Road, to the west of Portland).

A much more sustainable alternative configuration is shown below, in an illustration drawn from the Damascus project. This configuration allows for a jobs node, but one that is knit into the block and street pattern of the surrounding community with job-intensive blocks attached to, or one block away from, a major transit corridor.

When compared to conventional office park configurations, this plan provides easy access to transit lines -- which serve both these job sites and other land uses along the line.

Rule 4: Understand that jobs fit into blocks -- really they do!

Some say that modern job sites cannot fit into traditional block and street patterns. This is simply not true. Assuming a more or less standard North American block size of 320 by 640 feet, it can be shown that most jobs-intensive buildings, even the types now used in office parks, will easily fit into the four acres provided.

The occasional larger building can fit within two blocks combined to create a 640-by-640-foot, 10-acre block. Finally, should a community find itself with the happy circumstance of needing to accommodate a building or buildings that demand an even larger site, blocks up to 640 by 1,280 feet can be provided for a site of 20 acres without dramatically overloading the streets in surrounding blocks.

Rule 5: Accept that no home run is coming

Here we have what is often the most difficult barrier to sensibly integrating jobs into communities. It is the habit, common in many communities, of hoping for the "jobs home run."

Communities will commonly protect very large sites, through zoning for industrial use and placing minimum lot size restrictions on parcels so designated, in hopes of landing the massive Intel plant or the like.

This happens often enough to whet the appetites of municipal and regional officials (in a way not unfamiliar to habitual purchasers of lottery tickets). Thus, they stridently resist plans for interconnected street networks and traditional urban-scale blocks.

Meanwhile, more than 95 per cent of job sites consume far smaller sites, sites that can easily fit into five, 10 or 20 acres.

Rule 6. Understand that commercial strips are your friend

Finally, the reality is that in most first- and second-ring suburban communities, the land is used up. Where are the communities to find the acres required for even high-job-density facilities?

Brownfield sites are an option, but they are seldom found in suburban areas and at most cover less than one per cent of all urban lands. But there is one type of land that is much more common and is ripe for redevelopment in many forms, including jobs-intensive uses.

Low-density strip commercial areas, a legacy of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, are only marginally viable in present market circumstances. These strips are either former streetcar or interurban corridors in degraded form, or the product of freeway-induced devolvement on formerly rural roads.

Such sites consume 10 per cent or more of the land in first- and second-ring suburbs, land that is ripe for redevelopment and usually has an advantageous location within the region.

They are also almost always located on transit corridors, no matter how weak the current ridership, and are typically very suitable locations within which to reestablish the streetcar city form discussed earlier.

The worst offender

Of all the relationships that force our current overuse of energy, and our consequent enormous per capita production of GHG, the chaotic and tortured relationship between jobs and housing, and the impossibility of reasonably connecting them, is the worst.

It is, of course, unlikely that the historical pattern where all workers lived close to their jobs will be restored. But it is also true that no real progress in living more sustainably will be made unless we begin to reverse a trend that allows fewer than five per cent of all workers in the United States and Canada to conveniently access their jobs via transit; no amount of transit investment can solve the problem if the metropolitan matrix cannot be adapted for more equitable distribution of jobs and housing.

No amount of goodwill can get workers on transit if the backbone of the region's transportation infrastructure remains the freeway and the single-purpose and often exclusionary landscapes that are the inevitable spawn of such a system.

No amount of goodwill or heroic efforts at the local level will succeed without a policy context that enhances integration rather than thwarts it.

Finally, none of these proposed rules can hope to succeed unless federal, state and provincial monies are redirected toward a fundamental greening of the machinery of the metropolitan region -- its transit and transportation infrastructure.

Fortunately, simple and constitutional means exist that are equal to the challenge. Regional planning laws to induce housing and jobs equity are no dream; they exist.

The Oregon example

Oregon's land use law, after 30 years of struggle, threat and progress, has produced America's best current example of a coordinated jobs, housing and transportation strategy. Largely because of this law, the Portland region is the only North American region that is on track to meeting its own Kyoto-related GHG reduction targets.

Expecting a sea change in the criteria for allocating federal infrastructure dollars is no longer naive; such a change is already under way. In the Canadian context, the Vancouver area's Livable Region Strategic Plan, for all of its struggles and flaws, has produced a region where well over half of all new housing is in higher-density form in areas that are transit friendly.

With these policy and financial structures more broadly in place -- not just in Vancouver, not just in Oregon, but in every state and province -- local planners, developers and designers would have the support necessary to cure the disease.

It can be done

It won't happen in 10 years; it won't even happen in 20. Changes to cities take much longer than that.

But in 50 years? Yes. It has been done before; it can be done again.

Policy tools exist that, if strengthened, could produce equitable and low-GHG communities, communities that provide jobs and housing in equal balance, provide reasonable alternatives to the car for getting to work, and that integrate jobs seamlessly into the network of complete communities.

The six rules listed above for achieving this end, or other ones grounded in the same principles, provide a logical and practical way to heal our regions of a sickness. It is a sickness that drains our people of their money and energy while enforcing an economic segregation that violates our democratic principles.

Next: Rule 5 for Sustainable Communities -- Provide a diversity of housing types. ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: