An audit of provincial government ministries found just one that was highly prepared to continue its work after a major emergency such as an earthquake. The auditors found nine ministries were moderately prepared and nine more scored "low" marks.

And when the auditors took a close look at eight offices considered "mission critical" for the government -- including the ambulance dispatch centre, highways maintenance, the provincial emergency program and the provincial treasury -- what they found was dismal.

"Overall, we found there was a low level of compliance with core policy requirements, guidelines for developing and maintaining [Business Continuity Plans] were not consistently followed, and pandemic plans, although considered, have not yet been integrated."

The Internal Audit and Advisory Services report, "Report on the Cross Government Review of Business Continuity Management," based on fieldwork done between Oct. 2006, and March 2007, was quietly posted to the finance ministry's website in 2009.

A call to the ministry of public safety and solicitor general, which is responsible for emergency planning, to ask what steps may have been taken since the audit was not returned by publication time.

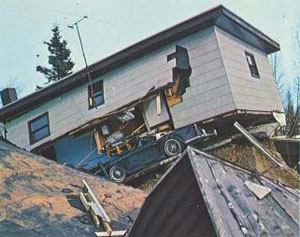

A little over two weeks ago a 7.0-magnitude earthquake leveled Port au Prince, Haiti, killing tens of thousands of people and crippling the Caribbean country's government. While British Columbia premier Gordon Campbell suggests the use of wood will help the province's buildings withstand a similar sized tremor and media reports consider the population's readiness for the big one, the audit report provides sobering reading.

Ministries lack plans

The 71-page report ranked 19 ministries on the "maturity" of their business continuity plans, the plans for how they will carry on after a major emergency.

The plans are needed, as the report puts it, "to [help] ensure the availability of government services, programs and operations, including all resources involved, and the timely resumption of services in the event of a major failure, emergency or disaster."

Only the ministry of small business and revenue as it was then called rated "high" for its planning. The nine ministries with the least developed plans included forests, environment, education, advanced education, children and family development, aboriginal relations, agriculture and lands, tourism and citizens' services.

The province had no government-wide plan to carry on its functions and "the business continuity coordination centre may not be adequately resourced to ensure an effective and efficient recovery effort across government."

That lack of planning means British Columbians shouldn't count on a quick return to normal, they found. "There is a significant risk to the continuity of key B.C. Government services in the event of a major emergency or wide area event."

The government website, by the way, warns that British Columbians should be prepared to look after themselves for at least 72 hours and as long as a week after a major disaster.

The auditors did note that after they did their field work, the government transferred management of some key areas to the newly created Emergency Management B.C. in April, 2007, bringing together emergency planning, the fire commissioner and the coroner service.

Lack of commitment

The authors of the report identified several "significant barriers" to improving ministry planning. The barriers included "minimal corporate commitment" in some ministries. The auditors found a "lack of dedicated resources" in some cases and in some there were "resources not sufficiently classified to have the right amount of influence."

It was unclear, they found, how much time it takes to plan how to continue work after an emergency, and there was "a shortage of trained staff within the ministries that possess the specific skills required to effectively analyse risks and business impacts, and facilitate the ongoing development and exercising of business continuity plans."

They made 30 recommendations for how ministries could improve their planning.

Even when the auditors turned their attention to eight areas considered "mission critical" for the government, as noted above, they found a lack of preparation. The areas included the provincial emergency program, the ambulance dispatch centre and others considered essential during an emergency.

This makes little sense in a geography prone to earthquakes, they found. "The high risk of earthquakes and tsunamis on the west coast require a wide scale emergency approach to business continuity planning," they wrote. "However, four plans did not consider wider-scale emergencies within their recovery strategies."

The plans for each office included alternate sites to use in case their normal headquarters can not be used. But in five of the eight cases the plans picked sites "within a close proximity" to their normal offices. In an event like an earthquake, if the head office was knocked out, the alternate site likely would be too.

Or as the report puts it: "Current literature on business continuity strategy suggests that alternate sites should be as far away as necessary from the principal operating site so as to avoid being subject to the same set of risks."

Resources, staff needed

A second audit report, "Report on Emergency Management Preparedness and Response," also quietly posted to the finance ministry's website last year and based on 2007 field work, found the "overall maturity of provincial emergency management through PEP is classified at the upper end of the medium range."

The authors argued for maintaining the staff and resources needed to deal with emergencies, even when everything is running smoothly. They recommended developing a human resources strategy to recruit, retain and train staff and volunteers in emergency management. Otherwise, they said, "both management and operation of the program will become increasingly difficult."

Many of the people responsible for emergency readiness are close to retirement, they noted. "The lead time necessary to train people for some roles means that the criticality of the issue could arrive very soon."

The auditors made their recommendations, keep in mind, at a time when the government's finances were healthy. It has since fallen into deficit spending and has been cutting jobs and looking for places to save money.

The auditors credited work done in the late 1990s that was done with a "strong strategic direction" and said establishing the EMBC in 2007 was an important step.

Much emergency response happens at the regional level, they found, co-ordinated by local governments. Ninety per cent of emergencies are handled locally, with the province stepping in during major events like floods, forest fires or earthquakes.

Municipalities with a "pro-active council, the tax base to support the required planning, prevention, and mitigation activities, and the vision to work with other communities in an integrated approach to emergency management" are relatively well prepared, they wrote.

"At the low end of the spectrum are non pro-active communities -- and others -- that have less comprehensive plans," they found. "Smaller communities must often rely on volunteer staff."

The authors noted that the Provincial Emergency Program does not formally review local government programs and plans or make sure they meet standards. "Training to necessary response levels is not mandatory," they noted. "There is no provincial training strategy, nor a database to identify gaps or needs."

Nor does the PEP make an effort to measure the effectiveness of its public education programs or the public understanding of what the government will be responsible for in an emergency. They write, "This could lead to unrealistic public expectations of incident response."

That means anyone who is watching Haitians dig out from their Jan. 12 earthquake and is telling themselves it would likely be different here, may well be mistaken. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: