Two strikes, two British Columbias.

In Vancouver, about 6,000 civic workers are off the job amidst a red-hot economy and the promise of greater riches from the 2010 Olympics.

Meanwhile, along the West Coast, about 7,000 forest workers are on strike in towns that have spent years grappling with job losses and economic change.

The Vancouver civic workers' strike is a reminder that life in a boomtown can have its downside, as workers complain of trying to keep up with soaring housing costs.

The coastal forestry strike is a reminder that not all of B.C. is booming -- a fact that those in boomtown tend to forget.

The civic workers support the new economy -- one based on knowledge and technology, services and construction.

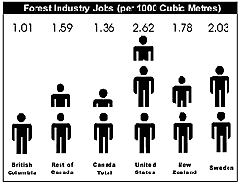

The forest workers are old economy -- part of an industry that used to dominate the B.C. economy but has lately been dwindling in terms of employment and economic impact.

Falling trees

Since 2004, when the most recent settlement was imposed on the coastal forest industry, 26 forest companies have gone out of business and about 5,000 loggers and sawmill workers have lost their jobs.

And that's just the latest decline in a long-term process. Employment in the coastal forest industry has dropped from more than 30,000 in the early 1980s to less than a third of that today.

The key issues in the forest dispute include contracting-out language, severance pay for partial mill closures, hours of work and shift scheduling. The union claims the companies are creating safety hazards by forcing workers to work longer hours and more days in a row.

The companies argue that they need more flexibility to survive, given increased competition and slumping markets.

As the industry has declined, the forest-dependent towns that dot Vancouver Island have diversified. Enterprises such as aquaculture and, especially, tourism have filled some of the gaps left by forest layoffs.

'Changed so much'

Twenty years ago, a coastal forest strike would bring headlines screaming Forest Strike Cripples Economy. Today, mill-town small businesspeople like Donna Streeter aren't sure just how much impact the strike will have.

Streeter is the general manager of Ricky's All Day Grill in Ladysmith. Two of her employees have spouses who work in the forest industry.

"Given that we're in the middle of summer and we have a fair bit of tourism trade, I'm not too sure how much it's going to affect us," she said.

If the strike lasts into the fall, after the tourists have gone home, then it will start to bite, she said.

In Port Alberni, Mayor Ken McRae remembers when the International Woodworkers of America had 5,000 members in his town alone. Today, the IWA has been merged into the United Steelworkers union. Contracting out means that many of the people working in the bush today don't belong to any union and aren't part of the strike.

"It's changed so much.... Now, especially in logging, there's a lot more non-union contractors. So they're all working," said McRae.

McRae was a negotiator for the Canadian Paperworkers' Union for a decade and president of the Port Alberni and District Labour Council for five years.

"So I know a lot about strikes."

At one time, he recalls, civic workers used to ask for the same wages as forest workers.

McRae laughs. "They used to strive for that in their contracts. Parity with the forest industry -- you don't hear that any more.

"It's the other way around, eh?"

'Question of survival'

Dave Hobden, an economist with Credit Union Central of B.C., says the trend is clear: "Forestry is not as important a part of the economy as it used to be overall, especially on Vancouver Island. It's a shrinking, sunset industry."

But that doesn't mean that an extended forest strike won't have an impact on coastal towns.

"It is true that they're more diverse, but some areas like Port Hardy, Alberni, Campbell River, Lake Cowichan, Duncan to some extent, even Nanaimo, Ladysmith, they still have a fairly high dependency on forestry income.

"In those areas it could cost them anywhere from 10 to 30 per cent of the income that's flowing in those economies."

Prices for forest products are low right now because of the slump in the U.S. housing market, he said.

"It's not a good time to be going on strike, there's no doubt about that."

If the strike goes on for several months, then the impact on Vancouver Island's economy will be significant, Hobden said.

"If it goes that long and longer, then it does become a question of survival for a lot of businesses."

While there will be political pressure to end the dispute, that pressure will be confined to the Island, he said.

Province interceded last time

The last coast forest shutdown, in 2003, ended after the provincial government stepped in. The government appointed arbitrator and mediator Don Munroe to work out a settlement that would reduce costs and bring stability to the industry.

The Munroe report led to "all sorts of changes in employment practices and contracting out," but it hasn't brought stability to the industry, said Simon Fraser University public policy professor Doug McArthur.

"At one time, until the mid to late '90s, there really was a kind of sense of collaboration between the union and the industry," said McArthur, a former senior civil servant with the B.C. government.

"They kind of served each other's interests. They made a kind of compact in the 1980s that they would go for an efficient, technology-based industry."

Some workers would lose their jobs, but those who remained would have both job security and high wages, he said.

"In the last six or seven years there has been just a really dramatic change where the industry has decided that the way to approach its cost challenges is to take it out of the wage bill," said McArthur.

The Munroe report, new tenure arrangements and market-based stumpage arrangements all helped to create a situation that eroded the old union-management understanding, McArthur said.

"There's no longer any kind of partnership in how they work together in the industry."

BC's 'core economy'

McArthur cited a number of long-term factors behind the current situation. Costs have increased because most of the easiest-to-reach stands of forest have been logged off. As well, employers went for years without investing in technology that would have made the industry more efficient and productive.

The softwood lumber export tax also added substantial costs.

The forest dispute, McArthur said, offers a sharp contrast to the civic workers' strike.

"There are two British Columbias, there's just no question about it. There's the Lower Mainland, the Fraser Valley, the Okanagan and the lower Island -- that's one British Columbia.

"And then there's most of the rest of British Columbia."

The resource-dependent northeast is enjoying an energy boom, but "the rest of B.C. is really suffering and workers are suffering and communities are suffering," McArthur said.

"There is a real economic crisis in these communities.... And I don't think the vast majority of people in the Lower Mainland, the Fraser Valley, the Okanagan, the lower Island have any idea what's going on.

"You have two different economies, one doing very well, and the other doing very badly, but you have a separation in terms of sympathies or understandings."

And, although the forest industry has declined over the years, it's still part of what McArthur describes as B.C.'s "core economy."

If energy prices drop and the construction boom dies after the Olympics, the province will be back to relying on the forest industry.

"So if it's not doing well, it will pull down the economy."

Related Tyee stories:

- BC's Crazy Timber Economics (series)

- Sawing off Our Future

BC's wide open timber industry is killing jobs, and people. - Strike Is All About the Olympics

But maybe not in the way you've heard.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: