Two years ago, when Vancouver became the first city in North America to open a safe injection site where people can use narcotics in a medically supervised setting, a storm of controversy ensued. Critics claimed that the facility, called Insite, would increase drug use and make taking drugs easier -- that addicts from all over the country would move to Vancouver.

These days it's clear that by providing a benign environment for injection drug users, Insite (located on the infamous 100 block of East Hastings) has, if anything, reduced the harm and severity of the drug problem in the Downtown Eastside. "Given how new Insite is, the results are amazing," says Dr. Thomas Kerr, a research scientist with the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, which is overseeing the evaluation of Insite. "There has been a substantial reduction of people injecting in public, less discarded syringes on the streets, reductions in needle sharing and elevated rates of entry into detoxification services."

Kerr's claims and the data backing him up haven't convinced the Conservative government to green-light the clinic permanently, however. "Given the need for more facts," said Health Minister Tony Clement on September 1, "I am unable to approve the current request to extend the Vancouver site for another three-and-a-half years."

A pilot project funded by the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, Insite also provides a point of contact for education, counselling and treatment. Its approach to street drug addiction is part of a philosophy and practice known as harm reduction. The central concept is to help people, without making judgments about their addiction or requiring them to stop using before receiving help. As Kerr says, "We have to invest in strategies that keep people alive and as healthy as possible until they get to that place where they quit on their own or their use stabilizes so they can manage their lives better.'' Many say this is an approach whose time has come for North America.

'Best thing in my life'

At Insite, staff initially worried that people might be slow to use the facility, says co-ordinator Sarah Evans. "But after four months we were running at maximum capacity." With 12 booths open 18 hours a day, Insite can handle up to 800 visits -- just a fraction of the number of injections happening daily in Vancouver. But many users, like Wayne and Carla, are willing to wait their turn for the measure of safety and security the site offers.

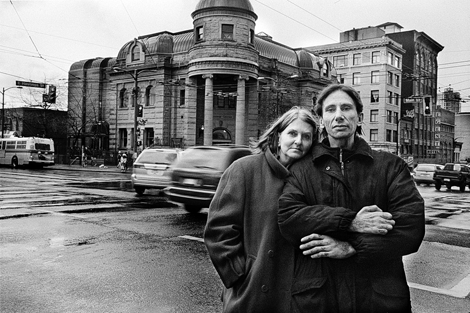

Both are injection drug users who travel from their apartment in Kitsilano to use the facilities at Insite. Because both are HIV and hepatitis C positive, infections and abscesses from unclean needles and paraphernalia could prove fatal for them. About 17 per cent of users at the facility are HIV positive.

Carla is an attractive, articulate woman in her early fifties. She grew up in a small town near Montreal where her parents owned a hotel. "I was well taken care of," she says. "I had everything I wanted. We had money. We lived by a lake. I skated. I skied. But I was a very high-strung kid, nervous and scared all the time. My mother didn't know what was wrong with me. I was afraid of airplanes. It was the time of the assassination of John F. Kennedy and they were saying scary things on television...I took it as being real. I had to tape down the blinds in my bedroom at night and tack the drapes to the wall. "

When Carla was 11 her mother took her to a pediatrician who put her on Librium. Ever since, Carla has been taking drugs in the benzodiazepine family for anxiety and panic attacks. During the '70s she experimented with hard drugs off and on but never became addicted until 1983, when her first husband died in a head-on collision in Montreal. She was working in the film industry at the time. "When I lost my husband, I started going out with a bisexual guy and fixing coke with him...anything to take away the reality."

Her present husband, Wayne, is 38, but seems older. "Wayne is the best thing in my life," Carla says. "I don't know what I would do without him...my biggest fear is being alone and dying...with Wayne I can share my fears, someone to be honest with who sees every side of you and still accepts and loves you." Lean and stoic, he looks like a sailor straight off the deck of a WWII merchant ship. His heavily tattooed right arm is lifeless from the elbow down after he accidentally injected a nerve two years ago, and he has a steel bar from his left knee to his ankle from an assault in 1999 during a botched robbery attempt he was involved in.

Wayne first injected LSD at a party when he was 14. "To be honest," he says, " I was petrified of needles. There was a big party. I was coerced into it. I had very low self-esteem. I wanted to be cool. I come from a small town just outside of Winnipeg. All my family were big drinkers.'' That same year Wayne's life in prison also began.

'Can conquer anything'

"My first conviction, for robbery, was when I was 14 years old," Wayne says. "I got nine months in juvenile detention. From there it was nothing but prison. I matured very quickly in prison. The worst part was the loneliness, being locked down and nobody there. I've been in the prison system most of my life. I was in the penitentiary twice, once in Winnipeg, and once in Drumheller. I started with property crime -- business, not residential -- then it escalated. I have eight years' experience as an industrial spray painter, which I learned in jail, but I can't work now because of my health."

Carla was diagnosed HIV positive in l998 and began to take HIV medications to fight the virus. At first she had a strong negative reaction. "A nurse came every day to my hotel to make sure I took it. I had nausea, headaches -- like the flu -- right away. But my numbers were great. Undetectable. It was like the operation was a success but the patient died. So I went off the meds and I got better. The ones I'm now on are great. I don't get sick at all."

Both Wayne and Carla take daily methadone, an oral synthetic opiate administered by a pharmacist. It has a long-lasting effect that stabilizes the nervous system but without the euphoric effect of heroin. Many people on methadone, which is a depressant, still use stimulants like cocaine and heroin to get high and overcome the slowing-down effect of the methadone. Wayne is not on antiretrovirals right now because they conflict with his methadone treatment -- to find a solution for this problem, he is having blood work done.

Before the safe injection site opened, Wayne and Carla injected in the alleys on the Downtown Eastside. "I had a rat run over my feet when I had a needle in my arm," Carla tells me. "That's the power of addiction. I was more concerned with my injection than the rat. This is not me at all. I still think about it and quiver. It just blows me away that I didn't stop immediately and scream."

"When you take that drug,'' Wayne says, ''whether you're smoking it or injecting it or snorting it, you get this euphoric feeling of 'nothing matters.' You could have a cable bill you haven't paid in three months, your life could be a total mess, a total disaster. You don't have a nickel in your pocket. You're at your wit's end and then you take the drug and none of these things bother you anymore. You have energy, you feel that you can conquer anything."

European import

Using opiates continually over the long term creates opiate dependency -- the drug is needed to generate an endorphin-like high. Bill Nelles, founder and director of the Methadone Alliance, a user-led group of activists and professionals in the United Kingdom (U.K.), talks about the long-term effect of opiate use on the brain. After six months or so of continual use, dependency takes place. "Opiates, unlike alcohol, are easy on the body," he says, "but what does happen is that the brain shuts down the whole endorphin system...In many, if not most users, these changes may not be reversible."

The Alliance, which is funded by the British government, does educational work and lobbies for better treatment and services for addicts, such as safe injection sites, inhalation rooms, prescription narcotics and detox. The first harm reduction initiatives, Nelles says, were taken in the early '80s by Amsterdam drug users who were worried about the spread of HIV and hepatitis C. "We took the Dutch work and brought it to the notice of the English-speaking world.''

A former opiate addict now on methadone, Nelles became addicted while he was a student nurse involved in a relationship with a doctor who easily obtained the drugs. No methadone program existed in eastern Canada in l977, although there was one in Vancouver. Because he had a British passport, Nelles chose to go to the U.K. to get into methadone treatment.

"All of the people I started doing opiates with in Ottawa are dead now," Nelles says. "We have this lovely idea that people who are addicted can come off the drugs if they want to...that they are making a choice to stay addicted."

Local experts

It's the users themselves, Nelles says, who are the experts on drug use. He credits the work of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) and its feisty director, Ann Livingston, for taking the lead in pushing for a safe injection site in Vancouver. In 2003, in response to a large-scale police crackdown and government inaction, VANDU, along with other like-minded organizations, opened an unsanctioned user-led safe injection site that operated for 181 days and supervised more than 3,000 injections.

Now VANDU is going to court to keep the Insite clinic open. "Hundreds of our members use Insite on a daily basis," said Diane Tobin, president of VANDU. "Many of them would be dead today without it. If this was a cancer treatment centre, they wouldn't hesitate, but because we're drug users it's like we don't matter."

According to Livingston, novice users coming to the Downtown Eastside area contract HIV and/or hepatitis C within six months. "If you grab 100 addicts, 35 of them are likely to be HIV positive and aboriginal people are seven or eight times more likely to be HIV positive.

"Because this place is like a village, people won't out themselves about their HIV. Everyone from the community will know. Their lives are already hard enough. But if nothing else is working for you, that's the last thing you'll do. Many have never taken AIDS meds. I call it dying with your boots on."

Tomorrow, second of two parts: the destruction drugs and related disease wreak in Insite's neighbourhood.

Elaine Brière is a Vancouver writer and photographer. Find her previous articles and images here.

This article originally appeared in The Positive Side magazine published by the Aids Information Exchange in Toronto.

A treatment guide for HIV-positive injection drug users and their caregivers is available at www.catie.ca/pdf/Prefix/enprefix.pdf or by calling 1.800.263.1638. For more info on harm reduction, visit www.canadianharmreduction.com. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: