The sudden concern over fake news — which is a feature of publishing as old as the printing press — strikes me as classic moral panic.

There’s nothing new about the bizarre stories found on the internet. We’ve long found them in tabloids like the National Enquirer. What is new is a wave of social upheaval — Brexit, Syria, the U.S. election — that has left us all looking for an uber villain to blame for why we suddenly feel so unsafe. Our lizard brains are convinced that if we could just police that villain, and jail him, censor him, or exclude him from society, we would all be safe again.

Fake news is the ideal target for a good moral panic. It’s vague and vaguely truthy, as Stephen Colbert would say, which makes it a shape-shifter that can be used to cast aspersions on anything or anyone you dislike. In the last few weeks I’ve read or heard critics blaming postmodernist theory for confusing people about what is true. Digital-phobes are blaming social media for spreading fake news. And journalists are accusing competitors of contributing to the fake news “crisis.”

I refer to that sanctimonious positioning as being more-accurate-than-thou, and I desperately hope that it’s just some hacks trying to get a competitive edge.

It was easy enough to ignore this growing moral panic when only Hillary Clinton and the Americans were banging the drum over “dangerous” fake news and calling for censorship. But last week that sentiment spilled over onto Canadian media. The publisher of the National Observer suggested that the Heritage Committee looking into the state of newspapers protect the public from this scourge by “certifying” journalists and establishing guidelines for what can be called journalism.

Given that Canada is a democratic country that has already balanced everyone’s rights with libel laws, hate speech laws, and Charter protections for freedom of speech, I assume the government will ignore her. Still, it’s disturbing when publishers themselves start lobbying for government censorship due to some exaggerated threat.

If you, like Clinton, think fake news is something new and digital, I suspect you haven’t bought groceries lately. The next time you need broccoli, find a checkout with a rack of tabloids and a long line-up and disabuse yourself of that notion. Also, be warned: there is no magic diet involving bananas.

Fake news is as old as the printing press (before that, it was just gossip). A few weeks ago, I wrote about The Attention Merchants, Tim Wu’s insightful book on the history of advertising, which tells us that North American news media have been making-up stories, for fun and profit, since 1833.

And before you assume one medium is more virtuous than another, just look at how books, the oldest of old media, have always had a vague definition of non-fiction. Particularly when it comes to memoirs. Consider the 2006 bestseller Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Mission to Fight Terrorism and Build Nations One School at a Time, in which Greg Mortenson told a heartwarming tale about a mountain climbing mishap that led to his rescue by some villagers in Pakistan. In gratitude, he launched a charity to build schools for them and thwart the Taliban.

That plot doesn’t sound plausible, but the book sold four million copies, due in no small part to coverage in many unquestioning news outlets. Then in 2011, journalist Jon Krakauer and 60 Minutes uncovered how Mortenson invented much of the charming story.

I know why so many news outlets believed that hopeful yarn about adorable children getting an education in a region plagued by war and poverty. Because it’s downright churlish to fact check either do-gooders or crime victims, particularly when children are involved.

The Devil’s in the flimsy details

Speaking of crime victims, back in 1980 when news and publishing standards were supposedly superior, there was a famously invented story with a local angle. The book Michelle Remembers was co-written by a Victoria psychiatrist, Lawrence Pazder and his patient-turned-wife Michelle Smith, about her alleged ritual sexual abuse at the hands of a Satan-worshipping cult in B.C.’s capital.

Michelle Remembers earned lots of ink and air from news media and that kicked off a panic about satanic ritual abuse in daycares. As Wikipedia documents, responsible news media, like Maclean’s magazine, investigated the story and found it flimsy. But that didn’t stop other media repeating it, including the powerful Oprah Winfrey talk show.

The hysteria around satanic abuse grew in the ‘80s and led to innocent daycare workers being accused and tried for imaginary crimes in circumstances that researchers later compared to the Salem witch trials. Some were even convicted by gullible juries.

Sociologist Stanley Cohen popularized the term moral panic after he wrote about one of the most famous incidents of media misinformation catching the public’s fancy in his 1972 book Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. It’s about the so-called seaside riots in England, in 1964, which inspired the story behind The Who’s film, Quadrophenia.

The epic battles were supposedly fought between Mods and Rockers, two fashionably dressed subcultures among British youth. Their passion for music and fashion knew no bounds, but Mods liked sharp suits, R&B, and Vespas. Rockers went for motorcycles, leathers, and rockabilly. Fights broke out over this.

How did anyone fall for a story so ridiculous? Well, as is often the case, there was a kernel of truth to it. Some brawls had broken out among bored young people who partied in the resort towns on weekends, and media commentators inferred the causes. Then hyped-up stories exaggerated the violence among stylish hooligans and they became that generation’s Millennials — the symbol of today’s youth destroying society.

Did someone say pizza?

Moral panics are really about vague anxieties connected to social upheaval. At the time, TV had everyone in a tizzy, the Cold War threatened, and that huge cohort of Baby Boomers became adults demanding social change. It was unsettling, and people needed someone to blame.

Which brings me to our latest round of irrational panic over the not-even-remotely-new problem of fake news. Last week a gunman attacked a Washington pizzeria, Comet Ping Pong, after online conspiracy theories claimed it was the headquarters of a pedophile ring run by Hillary Clinton and the Democrats. The restaurant owner, staff, and surrounding businesses all received death threats, online and by phone, and the FBI were already investigating those crimes when a gunman showed up and fired some shots.

It’s not clear why Edgar Maddison Welch, 28, a registered Republican from North Carolina, decided he was just the guy to look into pizzagate. Or why he was reportedly toting an unregistered assault rifle, a handgun, a rifle, and a folding knife. Or why, on hearing about a private citizen with a small arsenal shooting up a restaurant, anyone would think that fake news is the real problem?

Guy-with-guns obsessing over something and shooting celebrities or schools or workplaces might be called America’s central story. So before you get excited over the power of fanciful reports, you might want to ask yourself this: if being immersed in outrageous news leads to brandishing a gun, why aren’t thousands of journalists shooting off more than their mouths?

Trump: Truly dangerous

And here’s another question: if fake news is so damned influential, as Buzzfeed would have us believe, why did Trump attract substantially fewer voters than his Republican predecessors in 2008 and 2012?

Come to think of it, if news is such a motivator, why did 46 per cent of the American electorate stay home?

Who knows? I imagine there is a small army of political scientists trying to answer those questions even as I type.

Still, it’s not hard to spot the real cause of this moral panic over fake news. The idea of Trump anywhere near those nukes is giving the whole world the wiggins, and it’s reassuring to think that voters were somehow duped into electing a madman. The alternative explanation — that Americans support what Trump says and does — is just too frightening.

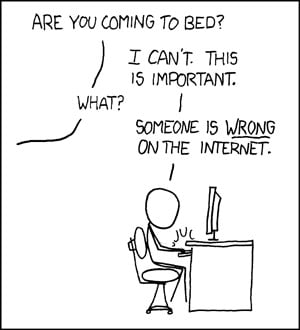

But blaming fake news for crazy behaviour is getting the equation backwards. We know that audiences choose the media outlets that confirm their worldview because they find that comforting. In other words, news media have always preached to the choir.

So it’s not that fake news made people love Trump; it’s that people who already loved Trump liked and circulated the fake news.

And what can anyone do about that?

I could mention outlets that fact check the fraudsters, like the excellent Snopes.com. Or note that NPR offers guidelines for fact checking a story. But if you’re savvy about the news you already know these things; and if you’re not, facts won’t persuade you.

We could face the obvious: that the fault is not in our news, dear readers, it is in ourselves. But speaking of unpleasant truths, who wants to believe that?

© Shannon Rupp. For permission to reprint this article please contact the author: shannon(at)shannonrupp.com. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: