It's seven in the morning when I arrive at the Granville Street Bridge on the south side of False Creek to go birding with 33-year-old artist and birder Jesse Garbe. Jesse is already waiting. He usually looks a bit like he has walked out of a 1960s hangout for working class British mods and been plunked down into current day Vancouver, but today is wearing a raincoat, a toque, gloves and a pair of binoculars hangs around his neck.

I come prepared with only my own mental categories for birds and I am trying to visualize each one, likely as some sort of warm up exercise. The very small ones I call sparrows. All of them. The black ones are all crows. I can identify pigeons, seagulls and owls but I can't differentiate between different species of each. (I later learn that there are over 50 species of gull in the world. I would've guessed a half dozen at best.) But all of the small birds I call sparrows.

Granville Island is still calm, with another hour or so before a flood of students arrive at Emily Carr, where Jesse is a sessional instructor. It's damp and dreary in that February-in-Vancouver way but it's not as cold as I had imagined it would be. I have managed to overdress in layers of socks and sweaters and my boyfriend's green raincoat. I feel awkward and puffy as Vancouverites jog by in their seasonal outdoor attire and I can't stop wondering why I have left my warm bed in my dry house where the coffee flows freely. I have never been birding. I don't know much about birds and I have a hard time believing that the birds that live in Vancouver will prove worth getting out of bed this early for.

I approached Jesse about birding for two reasons: first, to see why a successful young artist is so interested in and devoted to something that I had thought was more suited to my parent's peer group. Second, as a lifelong city-dweller and convenience-addict, I feel a deep desire to learn how to slow down and find some connection to nature. I am apprehensive about birds, however, because I have been shit on no less than six times. I can't help but note that all of these instances occurred prior to my decision to switch to a vegan diet.

Two Pacific loons

The term birding came about because birdwatching excluded the auditory aspect of listening to birds for identification and enjoyment. When I ask Jesse which term he prefers he shrugs. It's not that important to him what anybody calls it.

Like a good student I look at every bird that Jesse points out to me. He points to one bird floating solo against a backdrop of moored boats. "It's a Pacific loon!" My binoculars reveal a beautiful bird with black and white gradient stripes and a sharp bill. Very nice. He tell me this is very exciting because it's unusual for this species to be here at this time.

Jesse consults an app on his iPhone to help him confirm our sighting and I take the opportunity to observe some other habitats. Office building; condo; yacht. I look directly in on a kitchen where a woman is pouring Cheerios for two wild-haired children. She looks out the window in my direction and I drop my binoculars from my eyes. I immediately put them back on my eyes again but about 10 degrees away from her window. Just looking for birds, that's all.

Jesse began birding when he left for Nova Scotia to attend grad school in 2006. "When I moved to Halifax I was in a bit of a crisis. I really struggled with what I was going to make art about." He knew that he wanted to connect his interests in environmentalism, animal justice and natural history with his art practice, but he didn't know how to do it.

He had brought his dad's birding field guide with him to Halifax so he decided to just take it with him and walk. "I've always like walking around a new city, and birding gave me a reason to go further out of the city and into the surrounding areas. It also seemed like the perfect activity to spark thought about the perceived gap between human and nonhuman cultures."

Jesse found that birds, and nature in general, fit well into all of his artwork. He began painting pieces with titles like Toucan Diorama from the Kellogg's Hall of South American Birds and The Return Diorama (it's a painting of a pink panther). His work is as interesting to talk about as it is to look at. Even someone with little practical knowledge of art or birds can appreciate the ironic play on nature in pop culture.

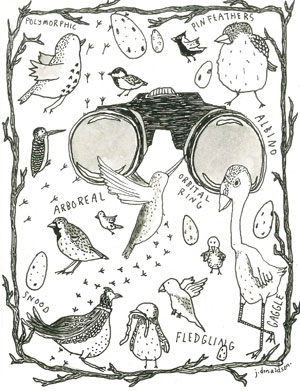

Birder skills

Jesse leads me along the False Creek seawall and I struggle to adapt from my frantic city-pace to his strolling pace. Birds bob on the calm water and I secretly hope to spot something rare and phenomenal. Not because I want to see it, but because I want the story. The way, as a child, I sat at the piano so deep in fantasy about my debut as a prodigy that I forgot to actually practice. Jesse brings me back from my daydream. "Birding also gives me something that feels like an escape." I can appreciate that.

I've borrowed a pair of binoculars from a friend and I'm listening to Jesse talk about bird habitats or something while he points to a bird in a tree that he wants me to see. The focus knob on my binoculars turns in two directions and both of them appear to achieve "fuzzy blob." My view eventually becomes clearer until the blob, perched atop a high branch, shows its perfect construction. It is a pinecone. The bird has hopped out of view and as Jesse waits patiently for the bird to emerge from the tree I fight off my desire to give the tree a swift kick so that the bird will fly out and we can see the damn thing.

Birding is the antithesis of everything I am used to and I am adverse to much of it right off the bat. I am not used to being still and I'm not very good at it. I am most comfortable when my hands and mind are very busy. I am inherently opposed to standing for extended periods of time, as well as cold weather, wet weather, and early mornings.

Birding requires extensive memorization so that you can go out with some knowledge of what you are looking for. It is a bit of a birder faux pas to head out into the field with an actual field guide. Instead, most birders take in-depth notes if they are unsure of a species. Colour, patterns, habits, tail shape, wing beats, flight styles. I can't help but think this is unnecessary and, in preparation for this outing, I brought my book to a bird sanctuary with me. I purchased a copy of the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America and it seemed perfectly reasonable to assume that I could just look up a bird on the spot.

What I failed to recognize was how long it would take to navigate this guide when I had no idea what grebes or tubenoses or alcids or jaegers were. I don't know how to decipher between sandpipers and phalaropes. Even when I overhear a five-year-old with pink binoculars and a plush mallard under her arm point out a warbler to her parents, I open my guide to find more than 50 possible species of warbler that frequent this region.

Jesse takes a notebook with him everywhere he goes to record his life-list. He is currently around 170. I begin to make a mental list of my own (writing them down feels like a bit of a commitment). I've seen plenty of robins and jays and my mother always makes me look at the window when I visit her to see the flickers eating from their half-dozen bird feeders. Can I put them on my list now or do I have to wait until I see them again once I've decided that I will make a list? Can I record my nondescript warbler? Do captive birds count? I've seen whatever birds lived at the San Diego Zoo in the mid-'90s. My cousin has an African Grey parrot. If I go visit her can I add that? I don't ask.

Windows in front of us

Jesse stops, abruptly. Stops walking and talking. "Listen. That's it." His favourite bird. The red-winged blackbird. All I had heard were my footsteps, my voice, and my thoughts with the sting of city noise in the distance. "Listen," he tells me. "That one." I hold my breath because it seems like the thing to do and I listen. It happens slowly, like your eyes adjusting to the night sky. First you see the North Star, then the big dipper and then, before you know it, the sky is amass with stars. I heard a bird. One bird with one distinct chirp. Another, another, and suddenly all I can hear are birds. I'm surrounded, absolutely surrounded by dozens of birds. At least dozens. I realize that there, along the False Creek seawall, between two bridges and facing Vancouver's plethora of glass condos, is nature. Actual nature doing its thing. Not just city birds getting by on city bugs but this massive ecosystem, and once I try all I can hear are birds.

Once I see a red-winged blackbird I can't believe I've never noticed them before. They are quite literally perfect. The males, anyways. The females, as with many bird species, are dressed down because they aren't in the business of attracting. The males are small and glossy with scarlet shoulder patches accented with a yellow stripe like epaulets on a proud coat. Understated but fancy.

I can't quite believe the ease with which Jesse manages to hear their calls without looking like he is trying or straining or having to ask me to just stop talking for a minute. In How to Be a Bad Birdwatcher, Simon Barnes talks about getting into the habit of having your mind and your eyes and your ears open (being a bad birdwatcher simply means that you see birds and enjoy them without worrying too much about binoculars and long life-lists). Like many hobbies, birdwatching needs to be practiced. You practice paying attention. You practice being available to see and hear the birds. Barnes' bad birdwatching is about taking away the formalities and just enjoying the birds in whatever way you wish.

I began to understand at the bird sanctuary. I was trying to focus on a bald eagle, perched high in a tree, when it occurred to me that, by virtue of binoculars blinding out all but about eight degrees of the world around you, my attention was focused on one tiny area (to be fair I wasn't actually focused unless I shut one eye). I, a person who seems constitutionally incapable of focusing on less than at least a half dozen unrelated things at any given moment, had narrowed down my field to one big bird.

Years ago I had a friend tell me about a rehab facility for substance abuse that he had gone to that had, in an effort to teach mindfulness and staying present, had made new patients carry around a hula hoop for the first week they were there. They were instructed to only pay attention to what they could see if they held up their hula hoop. What was directly in front of them. The rest could be dealt with or worried about later. Be here now. That was the point. That's one of the necessities of a successful birder.

Glass city hazards

A few weeks later Jesse and his French-Canadian girlfriend, fellow artist, Emily Carr instructor, and birder, Geneviève Raiche-Savoie, greet me at the door to their apartment. Jesse is dressed in a collared Fred Perry shirt and horn-rimmed glasses. Geneviève, with wavy black hair and bowed red lips seem much more pinup girl than outdoor enthusiast, which suggested to me that I may be the only one who doesn't -- or didn't think birding was cool.

Their apartment is lined wall-to-wall with books. A corner appears to be dedicated to fiction and the rest ranges from art; to philosophy; to natural history; to birding.

"Those are the books I'm reading at the moment." Jesse points to a stack of at least a half dozen encyclopedia sized books.

The pair have been working together on projects involving their shared interest in birds. Their latest work began with a six week residency at Terra Nova National Park in New Brunswick, from which they produced a field guide that explores the relationship between the composition of the gift shop's environment and merchandise and its relationship to the park.

Jesse and Geneviève have most recently started a project that looks at the problems between the urban architecture of Vancouver and migratory birds. It is estimated that approximately 100 million to one billion migratory birds are killed in a fatal crash with an urban obstacle each year in North America. It is the second leading cause of bird death, after habitat destruction. These numbers are expected to grow and the pair aim to find out what share in this Vancouver has.

Vancouver, like many cities, is filled with hazards to birds, such as reflective surfaces, bright lights, and glass windows. Birds can't differentiate between glass windows and fly through zones and they often fly towards them with disastrous results. Jesse's ultimate goal with this project is to help birds survive these crashes, track collisions and death tolls, educate both birds and humans about urban hazards, and to produce a type of window art that will be both appealing to urbanites and act as a warning sign for birds.

Several large cities have already been successful in implementing programs to help deal with migratory bird deaths due to urban structures. The City of Toronto launched the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) in 1993. Since then their volunteers have collected tens of thousands of injured or dead birds in the Toronto region. Over 80 per cent of the injured birds are rehabilitated and re-released into the wild. Unfortunately over 60 per cent of the birds are already dead when they are found.

Proper inter-disciplinarians

"I think I'm drawn to birds because they effectively straddle the boundary between what we think of as cultural and natural systems," Jesse says. "Birds are proper inter-disciplinarians. They appear in discourses on folklore, history, symbolism, art, science, ecology, aeronautics, and politics. Also, they are the wild animal that we come into contact with the most, which makes them accessible."

The truth is, we watch birds because they are there. They are everywhere. They are on every continent and in every country. They are more available for us to see than any other animal on earth and, no doubt, if there were ten thousand and some-odd species of goat travelling about the world we'd be watching them too.

Jesse says that birding has provided him with "a sense of wonder about the world" and hopes to make people more aware of the ecology of their cities through a program of research, rescue and education that takes into account non-human uses of the city. One of an estimated 60 million birders in North America, he hopes to direct some of this energy towards an evolving form of environmentalism that takes into account the social, historical, political, aesthetic and practical issues of urban areas.

After a few hours at the bird sanctuary I returned home with pink cheeks. I felt relaxed and it surprised me because it's a rarity. I had spent an entire morning doing a very un-Vancouver thing: looking up. Maybe I am beginning to understand Garbe's passion. Having any connection to nature will inevitably lead to a deeper concern for the environment and the non-human world around us.

A week later my boyfriend and I are sitting in the unseasonably warm sun at a cafe when a strange little bird with a sharp beak and yellow eyes begins to hop around on the table next to us.

"Babe, are you listening to me?"

"Just a minute. I want to know what kind of bird this is."

I snap a photo with my phone and save it so I can consult my field guide when I return home. I know one thing: it might be small, but it's definitely not a sparrow. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: