It was the summer of 1986. Al Anderson and I lived in a cabin on Chestermans Beach. One Sunday afternoon we got a case of beer and wandered out to Frank Island. When we got back, Laser Dave was waiting on the deck.

We called him Laser Dave because he spent his evenings lining up candles on the beach to show you where the planets would rise. He knew everything about the sky and the sea. He told us there was a three-foot swell headed this way. It had started a thousand miles out in the Pacific and was due to hit Tofino at 9:17pm. “It should wash right up the beach and knock the logs around,” he said.

It sounded exciting. Our cabin stuck right out of the salal, almost over top of the driftwood logs. We were front row central. I put my chair out on the deck and opened a beer. Ten minutes later Gwen showed up, breathless. “Did you hear?”

“Yeah, yeah, Laser told us, three feet, nine o’clock.”

“Three feet? No, it’s three metres. We have to go to Radar Hill.”

‘It’s 35 feet high!’

Radar Hill is the only high ground near Tofino that you can drive to. We call it Radar Hill because during the cold war the Feds built a top secret facility there that was obsolete before it was completed, so the village bought the building for a dollar and shipped it down to the lot beside the Schooner, where it became the fire hall. All that’s left on the hill are the old cement footings.

In case of a tsunami we’re all supposed to get up there ASAP. But that was for a full-on tsunami. A three-metre swell wasn’t going to kill anyone. I wanted to stay right where I was and watch the logs wash around.

A siren whooped outside. The new cop walked in through the lot and shouted up to us that there was a tsunami coming, it was five metres high, and the beach was being evacuated. This was serious. I opened another beer and watched Al and Gwen race around the cabin, arguing about what to take, shouting, grabbing blankets, apples, a pack of cards. I still couldn’t believe there was a real tsunami coming.

I went outside and gazed up at the clear blue sky. The sea was flat as a newly made bed, rumpled white along the shore. It was quiet. Too quiet. The air grew heavy with portent. The sun cast bible beams across the sand and in my mind’s eye I saw the waters suck back like in The Ten Commandments.

“Where’s the cat?” yelled Gwen. We couldn’t find her anywhere. Finally Al tore up all the bedding and there she was, cowering in terror. He grabbed the wretched animal and threw her inside his yellow Beetle, and she hid under the passenger seat and wouldn’t come out, and we raced back to the cabin to get Al’s sewing machine and Gwen’s manuscript and the rest of the beer, thinking “It’s true! It’s all true! And the animals know beforehand!” Turn off the gas. Grab a block of cheese. A hat. A book I’d never finish.

Diver Dave came tearing up the beach on a motorbike and yelled that the wave was only an hour away. “It’s thirty-five feet high! It’s thirty-five feet high!” Then he yelled something I didn’t catch, about an earthquake in the Bering Sea. I’d heard about some giant volcano up there. And hadn’t some scientist or psychic predicted a major earthquake? It all added up.

Waiting for the wave

The top of Radar Hill teemed with locals, and a lot of them had brought beer. Sulo Hovi alone had two flats in the trunk of his shiny black car. It was Psychedelic Sunday on Rock 101. Acid blared from car stereos, and a hippie kid in a green army jacket goose-stepped past with a boombox on his shoulder tuned to the weather station. That usually calm, pragmatic voice stammered like Porky Pig. “Th-th-there has been an earthquake off the coast of Alaska...”

The details were drowned in wail and chatter. Three-point-seven? Eight-point-seven? Something-point-seven. I yelled to Gwen, “There was an eight-point-seven earthquake in Alaska!” Her eyes went round. With her tousled hair she looked like Little Orphan Annie. “Fifty feet!” said Al. “Fifty feet!”

We gathered on the steep south face of the hill, staring into the setting sun, row upon row of anxious faces, like a grad photo from the school of hard knocks. Our houses, our record collections, our gardens... all gone. The wave had reached biblical proportions and could no longer be measured in feet or miles per hour.

Beside me, Kathy Lapyrous wept because she’d forgotten the baby photos. Next to her a tourist said, “I heard the warning on the radio, I passed the cops, I musta been doing 70!” He was having the time of his life because he had nothing to lose. Behind him, a beer-toting local said the Port Alberni tsunami of ’65 knocked houses on their sides, put a car in a tree, caused a million dollars‚ damage. “Ten million,” said his pal. “And it was ’64.”

Then a murmur passed through the crowd. “How big? How fast? When? Did you hear? It’s only 20 feet high.” Someone else said 15. Four people crouched around a radio. “SHHH!” The wave had just hit the Charlottes and was only five metres high. No, wait — five feet. Soon it was back to the original three.

A truck gunned its diesel. The new cop told us the warning was still in effect, but no one was listening. The acid rock swallowed the weather radio, and party hearty got the upper hand. Gwen decided to stay. Al and I got in the Beetle. The cat was still wedged under the seat. Dumb animal. Back in Tough City the bar was deserted and the TV still showed the emergency information screen. We took the last of the beer over to Barry’s house, where he and Crystal had watched the whole thing on TV.

In the years that followed there were two more warnings, and I ignored them both. But I wanted to have the choice, so I opened the back of the Loch Ryan’s two-way radio and peered inside.

An hour later, soaked with clammy sweat, I realized all it needed was a new fuse. I bought one at Whitey’s and immediately the little black box sputtered to life and began speaking in tongues. There were a hundred channels, which seemed excessive, but I soon found my way around the dial. Channel 82 was reserved for lighthouse keepers, 21 was the weather station, 16 was for emergencies, and 68 was where the Nuu-chah-nulth hung out.

All the rest were up for grabs, and you could talk to people for miles around: fishermen muttering in code about the day’s catch, hippies in isolated beach cabins, Native couples shouting at each other (“I wish you were here so I could hit you!”) and the occasional logging truck bouncing a signal off low cloud from up behind Kennedy Lake.

A world of connectivity

Much encouraged, I turned to the Loch Ryan’s three-ton diesel engine. There was an ancient owner’s manual in the nook beside the compass. Exploded diagrams revealed every bolt and gasket, beautifully rendered in shades of grey. On the front was my engine’s name: Allison. I hauled up the floor of the wheelhouse and there she was, her name stenciled across the rocker cover.

I thought, “I’ll treat her like a lady.” But Allison was no lady. She hunkered down and refused to work, like some bad-ass redneck bitch from Jerry Springer. She bit the skin off my knuckles. She hung me upside down till my eyes felt like bursting egg yolks. She ducked my head in the oily bilge until I looked like a balding Buckwheat.

I un-seized the brushes in the starter and replaced all the fuel filters and gaskets. I dismantled the blower. I figured out the fuel pump. But still she wouldn’t turn over. It looked like there were air bubbles in the fuel line. I had a nagging suspicion it had something to do with the very first fuel filter I’d replaced, but that filter shell lay deep in the belly of the boat, a dark region filled with sharp edges and wires that reeked of burnt peanuts, bilge, and diesel. I didn’t want to go back down there. Finally I dangled upside down into the engine room like a trapeze artist and unbolted the filter shell. I discovered I had pinched the gasket the first time I screwed the lid back on. That tiny rubber pucker had been the cause of all my grief.

When I twisted the key, how she roared! I lay on the dock feeling the throaty rumble through my back and looked up at the midnight sky. I thought, Hah! Some folks would pay a mechanic to do that. The night was quiet, except for Allison. I was exhausted. This was why I froze like a jackrabbit in high beams every time I saw a machine. So many parts. Each of the parts was simple in itself, but every part had to work, or nothing worked at all. I had always been afraid to look at the world in terms of its parts, in case I lost track of the big picture and disaster ensued. But now that Allison was in my life I had no choice. I’d have to keep one eye on the whole and one on the parts, even if it drove me mad.

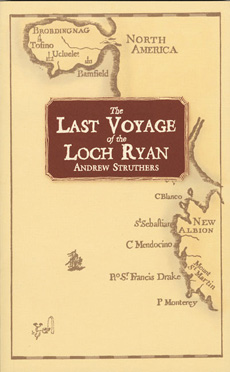

Andrew Struthers is a Victoria writer and film-maker. The Last Voyage of the Loch Ryan (New Star) was published in September, and traces Struthers’ life aboard a decommissioned wooden fish boat.

![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: