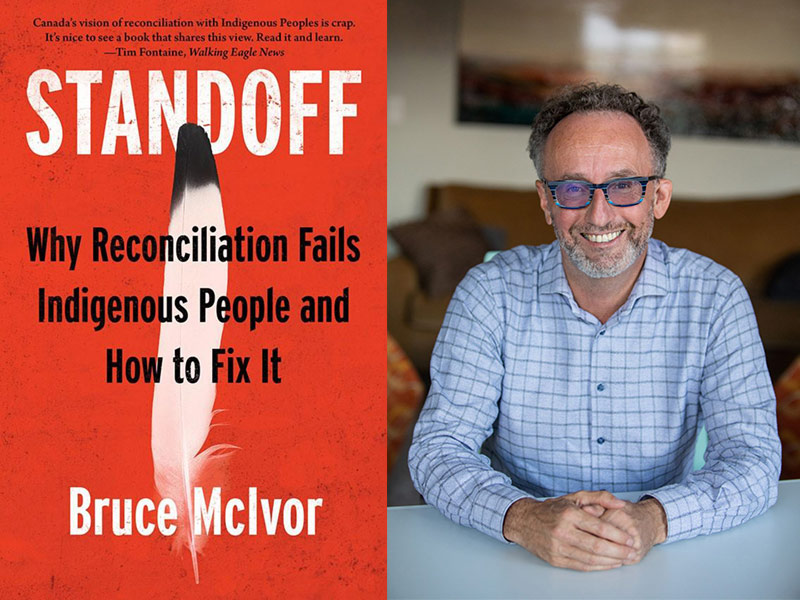

[Editor’s note: Occasional Tyee contributor Bruce McIvor is a member of the Manitoba Métis Federation and a partner at First Peoples Law LLP, a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing Aboriginal title, Aboriginal rights and treaty rights. In 'Standoff,' he expertly lays out the case for why reconciliation, positioned as a salve during the Justin Trudeau era, is not working for Indigenous peoples. 'Reconciliation continues to fail because it rests on a foundation of systemic racism,' McIvor writes. 'It is predicated on the denial of Indigenous peoples’ inherent rights.' In the following excerpt, McIvor delves into why reconciliation cannot be possible while Canada continues to engage in violence as a tactic to undermine Indigenous rights and sovereignty.]

I spend a lot of time in small towns across Canada. Often, I go for lunch with my First Nations clients. With one of my clients, I noticed that we always ate at the same local restaurant over and over again, despite there being what seemed to be several other perfectly good places to eat. When I finally suggested we try one of those restaurants for a change, the response from my clients jarred me out of my comfortable complacency: This is where we feel safe, they said.

The threat and reality of violence is at the core of Indigenous experiences with non-Indigenous Canada. My clients live with the threat of violence their entire lives. Violence inflicted on them and their loved ones by non-Indigenous people.

From an early age, they learn the cruel reality that being a visibly identifiable Indigenous person in Canada means they live with a heightened risk of being insulted, attacked and killed by non-Indigenous people.

From Colten Boushie to Tina Fontaine to a grandfather and his granddaughter handcuffed outside a bank in downtown Vancouver, violence against Indigenous people is the Canadian reality.

It is a violence that extends beyond the personal. It has been an ever-present tool in the colonization and continuing oppression and displacement of Indigenous people in Canada.

From Indigenous perspectives, Canadian history is a horror show of violence. From Governor Cornwallis’ on Mi’kmaw scalps, to military attacks on the fledgling Métis Nation, to Louis Riel hanged in Regina, to John A. Macdonald’s policy of starvation of the Plains Cree, to Poundmaker’s imprisonment, to the hanging of Tsilhqot’in Chiefs, to residential schools and the '60s Scoop, the list goes on and on.

Importantly, Canadian state-sanctioned violence against Indigenous people is not simply a matter of history and easy apologies. It is a modern-day reality. Think back over the last 20 years: Oka, Gustafsen Lake, Ipperwash, Burnt Church, Elsipogtog, Unist’ot’en.

On Feb. 6, 2020, my Wet’suwet’en clients in northern British Columbia again faced the reality of what it too often means to be an Indigenous person in Canada. While Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs and their supporters seek to defend their land against a multinational pipeline company and a provincial government that appears to believe reconciliation occurs at the end of a gun, the RCMP again amassed an armed force in an attempt to overwhelm and subdue them.

In preparation for a similar military-style raid against my clients last year, the RCMP employed a strategy of “lethal overwatch” and using as much violence as they deemed necessary to “sterilize the site.”

This time around, the RCMP assured Canadians that the police officers tasked with dismantling Wet’suwet’en camps, handcuffing unarmed land protectors and marching them off to jail had first undergone cultural awareness training.

For many Indigenous people, the very language of “peace, order and good government” is infused with and inseparable from real, visceral, frightening experiences of violence.

On a blustery day in northern Ontario, over 100 miles from the nearest road, I informed Anishinaabe clients that the provincial government was finally willing to sit down and explore avenues for them to exercise their inherent Indigenous “jurisdiction.”

The Elders politely smiled, turned away and spoke among themselves in Oji-Cree. After a few minutes, as often happens, I was told a story.

It was a story about being a child and wanting to visit cousins in the neighbouring community downriver. Of travelling in an open boat, of rounding a bend in the river and seeing cousins handcuffed to poplar trees.

For my clients, the word jurisdiction didn’t connote fairness, justice and the rule of law. It conjured visions of the personifications of government and institutional authority, the priest, the RCMP officer, the Indian Agent — the people who handcuffed their cousins to poplar trees.

The threat and reality of violence extends beyond language. It has become part of the built environment that contains and defines our daily experiences.

I grew up in rural Manitoba on the fringes of the Peguis First Nation reserve. My mother held a wide variety of jobs. I thought she could do anything. I still do. One of her jobs was working in the beer parlour in the hotel in a nearby small town.

Occasionally after school I’d wait at the hotel until her shift ended. Hoping to get a few dollars to buy a serving of french fries in the adjoining diner, I’d grip the counter at the off-sales window, pull myself up and look into the beer parlour, straining to get my mom’s attention as she served draft beer and punched out change from the coin belt around her waist.

The room was dingy with a dirty carpet soaked in cheap beer. A low steel fence ran down the middle of the room, dividing it in two. I asked my mom, “Why is there a fence?” Her answer brought many of my childhood experiences into focus: “It’s to separate the Indians from the white guys.” Any Indigenous person daring to sit on the wrong side of that fence risked a severe beating.

When I hear the word reconciliation, I think of that fence. I think of how it represents Canada’s long history of segregating Indigenous people and perpetuating violence against them.

Violence towards Indigenous people, personal, institutional and state-sanctioned, is woven into the very fabric of Canadian life, both its history and its present. It is in the words we speak and the buildings and cities we inhabit. Canadian law sanctions it, politicians justify it, industry profits from it, the public turns a blind eye.

With the RCMP raid on the Wet’suwet’en, violence also became the hallmark of reconciliation.

Excerpted from ‘Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It’ by Bruce McIvor. Copyright © 2021 Bruce McIvor. Published by Nightwood Editions. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: